„Störung der Sinnesverarbeitung“ – Versionsunterschied

| [ungesichtete Version] | [ungesichtete Version] |

Sensory integration dysfunction has now been merged into this article |

→Autistic spectrum disorders and difficulties of sensory processing: Anxiety disorders and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders: is there a causal relationship |

||

| Zeile 123: | Zeile 123: | ||

=== Autistic spectrum disorders and difficulties of sensory processing === |

=== Autistic spectrum disorders and difficulties of sensory processing === |

||

Sensory processing disorder is a common comorbidity with [[autism spectrum disorder]]s.<ref name="Russo 2010">{{cite journal |author=Russo N, Foxe JJ, Brandwein AB, Altschuler T, Gomes H, Molholm S |title=Multisensory processing in children with autism: high-density electrical mapping of auditory-somatosensory integration |journal=Autism Res |volume=3 |issue=5 |pages=253–67 |year=2010 |month=October |pmid=20730775 |doi=10.1002/aur.152 |url=}}</ref> Although responses to [[Stimulus (physiology)|sensory stimuli]] are more common and prominent in autistic children and adults, there is no good evidence that sensory symptoms differentiate [[autism]] from other developmental disorders.<ref> |

Sensory processing disorder is a common comorbidity with [[autism spectrum disorder]]s.<ref name="Russo 2010">{{cite journal |author=Russo N, Foxe JJ, Brandwein AB, Altschuler T, Gomes H, Molholm S |title=Multisensory processing in children with autism: high-density electrical mapping of auditory-somatosensory integration |journal=Autism Res |volume=3 |issue=5 |pages=253–67 |year=2010 |month=October |pmid=20730775 |doi=10.1002/aur.152 |url=}}</ref><ref name="Green 2010">{{cite journal |author=Green SA, Ben-Sasson A |title=Anxiety disorders and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders: is there a causal relationship? |journal=J Autism Dev Disord |volume=40 |issue=12 |pages=1495–504 |year=2010 |month=December |pmid=20383658 |pmc=2980623 |doi=10.1007/s10803-010-1007-x |url=}}</ref> Although responses to [[Stimulus (physiology)|sensory stimuli]] are more common and prominent in autistic children and adults, there is no good evidence that sensory symptoms differentiate [[autism]] from other developmental disorders.<ref> |

||

{{cite journal |

{{cite journal |

||

|journal= J Child Psychol Psychiatry |

|journal= J Child Psychol Psychiatry |

||

Version vom 20. Juli 2013, 12:04 Uhr

Sensory processing disorder or SPD is a group of neurological disorders in which the person presents abnormalities in the neurological process known as multisensory integration. Failure to organize sensation coming from multiple modalities, such as proprioception, vision, auditory system, tactile, olfactory, vestibular system, interoception, and taste results in difficulties in function. The capacity to use multisensory integration to adequately function in life is called Sensory processing by Occupational therapy and dysfunction Sensory processing disorder.

Previously known as Sensory Integration, Sensory processing was defined by Dr Anna Jean Ayres PhD, OTR who was both an occupational therapist and an educational psychologist[1] in 1972 as "the neurological process that organizes sensation from one's own body and from the environment and makes it possible to use the body effectively within the environment". Different people experience a wide range of difficulties when processing input coming from different senses. For example, some people find wool fabrics itchy and hard to wear while others don't and some individuals might experience movement sickness while ridding amusement park games while their friends are having fun. Sensory processing disorder however, is characterized by significant problems to organize sensation coming from the body and the environment and manifested by a significant difficulty in one of more of the main areas of occupation: productivity, leisure and play or activities of daily living. [2]

Classification

Sensory processing disorders are classified into 3 broad categories: Sensory modulation disorder, Sensory based motor disorders and Sensory discrimination disorders.[3]

- Type I – Sensory modulation disorder

- Subtypes: over-responsivity, under-responsivity and sensory craving (seeking)[4]

- Type II – Sensory-based motor disorder

- Subtypes: postural disorder, dispraxia

- Type III – Sensory discrimination disorder

- Subtypes: visual, auditory, tactile, taste/smell, position/movement, interoception

Sensory modulation disorder (SMD)

Over, or under responding to sensory stimuli or seeking sensory stimulation. Sensory modulation refers to a complex central nervous system process[5] by which neural messages that convey information about the intensity, frequency, duration, complexity, and novelty of sensory stimuli are adjusted.

This group may include a fearful and/or anxious pattern, negative and/or stubborn behaviors, self-absorbed behaviors that are difficult to engage or creative or actively seeking sensation.[4]

Sensory-based motor disorder (SBMD)

Shows motor output that is disorganized as a result of incorrect processing of sensory information affecting postural control challenges and/or dyspraxia.

Sensory discrimination disorder (SDD)

Sensory discrimination or incorrect processing of sensory information. Incorrect processing of visual or auditory input, for example, may be seen in inattentiveness, disorganization, and poor school performance.

Causes

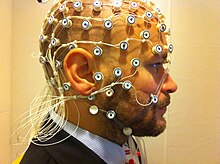

Current research in sensory processing is focusing on finding the neurological causes of SPD. EEG and Event-related potential are traditionally used to explore the causes behind the behaviors observed in SPD. Some of the proposed underlying causes by current research are:

- People with SPD have less sensory Gating (electrophysiology) than typical subjects.[6][7]

- People with Sensory over responsivity might have increased D2 receptor in the striatum, related to aversion to tactile stimuli and reduced habituation. In animal models, it has been observed the effect of prenatal stress on tactile avoidance, where prenatal stress significantly increased the avoidance.[8]

- Recent research by Owen and colleagues (2013)[9] at the University of California, San Francisco have found a neurological difference in children with SPD, compared to normal children and those with other neurological disorders such as autism and ADHD.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may vary according to the disorder's type and subtype present,

People suffering from over responsivity might:

- Dislike textures in fabrics, foods, grooming products or other materials found in daily living, to which most people would not react to and this dislike interferes with normal function. Like a child who refuses to wear underwear or a grown up who is so "picky" he can't go to restaurants with friends.

- Get so car sick they refuse to be in a moving vehicle.

- Refuse to kiss or hug, not because they don't like the person, but because the sensation of skin contact can be very negative

- Feel seriously discomforted, sick or threatened by normal sounds, lights, movements, smells, tastes, or even inner sensations as heartbeat.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Sensory integration therapy

Several therapies have been developed to treat SPD. Some of these treatments (for example, sensorimotor handling) have a questionable rationale and no empirical evidence. Other treatments (for example, prism lenses, physical exercise, and auditory integration training) have had studies with small positive outcomes, but few conclusions can be made about them due to methodological problems with the studies.[10] Although replicable treatments have been described and valid outcome measures are known, gaps exist in knowledge related to sensory integration dysfunction and therapy.[11] Empirical support is limited, therefore systematic evaluation is needed if these interventions are used.[12]

The main form of sensory integration therapy is a type of occupational therapy that places a child in a room specifically designed to stimulate and challenge all of the senses.

During the session, the therapist works closely with the child to provide a level of sensory stimulation that the child can cope with, and encourage movement within the room. Sensory integration therapy is driven by four main principles:

- Just Right Challenge (the child must be able to successfully meet the challenges that are presented through playful activities)

- Adaptive Response (the child adapts his behavior with new and useful strategies in response to the challenges presented)

- Active Engagement (the child will want to participate because the activities are fun)

- Child Directed (the child's preferences are used to initiate therapeutic experiences within the session).

Children with lower sensitivity (hyposensitivity) may be exposed to strong sensations such as stroking with a brush, vibrations or rubbing. Play may involve a range of materials to stimulate the senses such as play dough or finger painting.

Children with heightened sensitivity (hypersensitivity) may be exposed to peaceful activities including quiet music and gentle rocking in a softly lit room. Treats and rewards may be used to encourage children to tolerate activities they would normally avoid.

While occupational therapists using a sensory integration frame of reference work on increasing a child's ability to tolerate and integrate sensory input, other OTs may focus on environmental accommodations that parents and school staff can use to enhance the child's function at home, school, and in the community (Biel and Peske, 2005).[13][14] These may include selecting soft, tag-free clothing, avoiding fluorescent lighting, and providing ear plugs for "emergency" use (such as for fire drills).

There is a growing evidence base that points to and supports the notion that adults also show signs of sensory processing difficulties. In the United Kingdom early research and improved clinical outcomes for clients assessed as having sensory processing difficulties is indicating that the therapy may be an appropriate treatment (Urwin and Ballinger 2005)[15] for a range of presentations seen in adult clients including for those with Autism and Asperger's Syndrome, as well as adults with dyspraxia and some mental health difficulties [16] that therapists suggest may arise from the difficulties adults with sensory processing difficulties encounter trying to negotiate the challenges and demands of engaging in everyday life (Brown, Shankar and Smith 2006).[17]

Epidemiology

Relationship to other disorders

Because comorbid conditions are common with sensory integration issues, a person may have other conditions as well.People who receive the diagnosis of sensory integration dysfunction may also have signs of anxiety problems, ADHD, food intolerances, and behavioral disorders and other disorders.

Autistic spectrum disorders and difficulties of sensory processing

Sensory processing disorder is a common comorbidity with autism spectrum disorders.[18][19] Although responses to sensory stimuli are more common and prominent in autistic children and adults, there is no good evidence that sensory symptoms differentiate autism from other developmental disorders.[20] Differences are greater for under-responsivity (for example, walking into things) than for over-responsivity (for example, distress from loud noises) or for seeking (for example, rhythmic movements).[21] The responses may be more common in children: a pair of studies found that autistic children had impaired tactile perception while autistic adults did not.[22]

SPD and ADHD

It is speculated that SPD may be a misdiagnosis for persons with attention problems. For example, a student who fails to repeat what has been said in class (due to boredom or distraction) might be referred for evaluation for sensory integration dysfunction. The student might then be evaluated by an occupational therapist to determine why he is having difficulty focusing and attending, and perhaps also evaluated by an audiologist or a speech-language pathologist for auditory processing issues or language processing issues. Similarly, a child may be mistakenly labeled "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)" because impulsivity has been observed, when actually this impulsivity is limited to sensory seeking or avoiding. A child might regularly jump out of his seat in class despite multiple warnings and threats because his poor proprioception (body awareness) causes him to fall out of his seat, and his anxiety over this potential problem causes him to avoid sitting whenever possible. If the same child is able to remain seated after being given an inflatable bumpy cushion to sit on (which gives him more sensory input), or, is able to remain seated at home or in a particular classroom but not in his main classroom, it is a sign that more evaluation is needed to determine the cause of his impulsivity.

Other comorbidities

Various conditions can involve SID, such as schizophrenia,[23][24][25] succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency,[26]primary nocturnal enuresis,[27] prenatal alcohol exposure, learning difficulties[8] and autism,[28][29][30] as well as people with traumatic brain injury[31] or who have had cochlear implants placed.[32] and may have genetic problems such as Fragile X syndrome. Sensory integration dysfunction is not considered to be on the autism spectrum, and a child can receive a diagnosis of sensory integration dysfunction without any comorbid conditions.

Controversy

Manuals

SPD is in Stanley Greenspan’s Diagnostic Manual for Infancy and Early Childhood and as Regulation Disorders of Sensory Processing part of the The Zero to Three’s Diagnostic Classification.[33] but is not recognized in the manuals ICD-10[34] or the DSM-IV-TR,[35]

The American Psychiatric Association recently rejected SPD as a diagnosis to be included in the recently updated DSM-5.[36] but has included abnormalities in sensory modulation as the 4th main criteria for Autism diagnosis

Misdiagnosis

Some state that sensory processing disorder is a distinct diagnosis, while others argue that differences in sensory responsiveness are features of other diagnoses.[37] The American Academy of Pediatrics, for example, advises against a diagnosis of SPD unless it is a symptom due to autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, developmental coordination disorder, or childhood anxiety disorder.[38] The neuroscientist David Eagleman has proposed that SPD may be a form of synesthesia, a perceptual condition in which the senses are blended.[39] Specifically, Eagleman suggests that instead of a sensory input "connecting to [a person's] color area [in the brain], it's connecting to an area involving pain or aversion or nausea".[40][41][42]

Researchers have described a treatable inherited sensory overstimulation disorder that meets diagnostic criteria for both attention deficit disorder and sensory integration dysfunction.[43]

Research

Over 130 articles on sensory integration have been published in peer-reviewed (mostly occupational therapy) journals. The difficulties of designing double-blind research studies of sensory integration dysfunction have been addressed by Temple Grandin and others. More research is needed.

Because the amount of research regarding the effectiveness of SPD therapy is limited and inconclusive, the American Academy of Pediatrics advises pediatricians to inform families about these limitations, talk with families about a trial period for SPD therapy, and teach families how to evaluate therapy effectiveness.[38]

History

Sensory processing disorders were first described in-depth by occupational therapist Anna Jean Ayres (1920–1989),. According to Ayres's writings, an individual with SPD would, therefore, have a decreased ability to organize sensory information as it comes in through the senses.[44]

Ayres model

Ayres theoretical frame about what she called Sensory integration was developed after 6 factor analytic studies of populations of children with learning disabilities, perceptual motor disabilities and normal developing children. Referenzfehler: Ungültiger Parameter in <ref>.

Dr. Ayres created the following nosology based on the patterns that appeared on her factor analysis:

- Dispraxia: poor motor planning (more related to vestibular and proprioception)

- Poor bilateral integration: Inadequate use both sides of the body simultaneously

- Tactile defensiveness: Negative reaction to tactile stimuli

- Visual perpceptual deficits: poor form and space perception and visual motor functions

- Somatodispraxia: poor motor planning (related to poor information coming from the tactile and proprioceptive systems)

- Auditory-language problems

Both visual perceptual and auditory language deficits were thought to posses a strong cognitive component and a weak relationship to underlying sensory processing deficits so they are not considered central deficits in many models of Sensory processing.

In 1998, Mulligan performed a study on 10,000 sets of data, each representing an individual child. She performed confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses and found similar patterns of deficits with her data as Ayres did. [45]

Dunn model

Dunn's nosology uses two criteria[46] : response type (passive vs active) and sensory threshold to the stimuli (low or high) creating 4 types:

- low registration, high threshold with passive response.

- sensory avoiding, low threshold and active response.

- sensory seeking, high threshold and active response.

- sensory sensitive, low threshold with passive response.

Miller model

Lucy Jane Miller, Ph.D., OTR, proposed a new nosology, where dysfunction was changed to disorder and Sensory integration was changed to Sensory processing to facilitate coordinated research work with other fields such as Neurology, for example " the use of the term sensory integration often applies to a neurophysiologic cellular process rather than a behavioral response to sensory input as connoted by Ayres." [47]

The current nosology of Sensory processing disorders was developed by Dr. Miller, based on neurological underlying principles.

Other models

A wide variety of approaches have incorporated sensation in order to complement sensory-based strategies. [45]

- The Alert Program for Self-Regulation is a complementary approach that encourages cognitive awareness of alertness often with the use of sensory strategies to support learning and behavior.

- Other approaches primarily use passive sensory experiences or sensory stimulation based on specific protocols, such as the Wilbarger Approach and the Vestibular-Oculomotor Protocol.

See also

References

External links

Vorlage:Pervasive developmental disorders Vorlage:Autism resources Vorlage:Autism films

- ↑ Sensory Integration (SI) | USC Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy.

- ↑ Sensory Processing Disorder Explained. SPD Foundation

- ↑ Lucy Jane Miller, Anzalone, Marie E.; Lane, Shelly J.; Cermak, Sharon A.; Osten, Elizabeth T.: Concept evolution in sensory integration: A proposed nosology for diagnosis. In: American Journal of Occupational Therapy (= 2). 61. Jahrgang, S. 135–140, doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.135 (apa.org [abgerufen am 19. Juli 2013]).

- ↑ a b James K, Miller LJ, Schaaf R, Nielsen DM, Schoen SA: Phenotypes within sensory modulation dysfunction. In: Compr Psychiatry. 52. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, 2011, S. 715–24, doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.010, PMID 21310399 (spdfoundation.net [PDF]).

- ↑ Schaaf RC, Benevides T, Blanche EI, et al.: Parasympathetic functions in children with sensory processing disorder. In: Front Integr Neurosci. 4. Jahrgang, 2010, S. 4, doi:10.3389/fnint.2010.00004, PMID 20300470, PMC 2839854 (freier Volltext) – (spdfoundation.net [PDF]).

- ↑ Davies PL, Chang WP, Gavin WJ: Maturation of sensory gating performance in children with and without sensory processing disorders. In: Int J Psychophysiol. 72. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, Mai 2009, S. 187–97, doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.12.007, PMID 19146890, PMC 2695879 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Kisley MA, Noecker TL, Guinther PM: Comparison of sensory gating to mismatch negativity and self-reported perceptual phenomena in healthy adults. In: Psychophysiology. 41. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, Juli 2004, S. 604–12, doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00191.x, PMID 15189483 (spdfoundation.net [PDF]).

- ↑ a b Schneider ML, Moore CF, Gajewski LL, et al.: Sensory processing disorder in a primate model: evidence from a longitudinal study of prenatal alcohol and prenatal stress effects. In: Child Dev. 79. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 2008, S. 100–13, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01113.x, PMID 18269511 (sinetwork.org [PDF]). Referenzfehler: Ungültiges

<ref>-Tag. Der Name „Schneider 2008“ wurde mehrere Male mit einem unterschiedlichen Inhalt definiert. - ↑ Julia P. Owen, Elysa J. Marco, Shivani Desai, Emily Fourie, Julia Harris, Susanna S. Hill, Anne B. Arnett, Pratik Mukherjee: Abnormal white matter microstructure in children with sensory processing disorders. In: NeuroImage: Clinical. 2. Jahrgang, 2013, ISSN 2213-1582, S. 844–853, doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2013.06.009.

- ↑ Baranek GT: Efficacy of sensory and motor interventions for children with autism. In: J Autism Dev Disord. 32. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, 2002, S. 397–422, doi:10.1023/A:1020541906063, PMID 12463517.

- ↑ Schaaf RC, Miller LJ: Occupational therapy using a sensory integrative approach for children with developmental disabilities. In: Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 11. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, 2005, S. 143–8, doi:10.1002/mrdd.20067, PMID 15977314.

- ↑ Hodgetts S, Hodgetts W: Somatosensory stimulation interventions for children with autism: literature review and clinical considerations. In: Can J Occup Ther. 74. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, 2007, S. 393–400, doi:10.2182/cjot.07.013, PMID 18183774.

- ↑ Nancy Peske; Lindsey Biel: Raising a sensory smart child: the definitive handbook for helping your child with sensory integration issues. Penguin Books, New York 2005, ISBN 0-14-303488-X.

- ↑ Sensory Checklist. In: Raising a Sensory Smart Child. Abgerufen am 16. Juli 2013.

- ↑ Urwin R, Ballinger C.: The Effectiveness of Sensory Integration Therapy to Improve Functional Behaviour in Adults with Learning Disabilities: Five Single-Case Experimental Designs. In: Brit J. Occupational Therapy. 68. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, Februar 2005, S. 56–66 (ingentaconnect.com).

- ↑ Stephen Brown, Rohit Shankar, Kathryn Smith: Borderline personality disorder and sensory processing impairment. In: Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry. 13. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, 2009, ISSN 1367-7543, S. 10–16, doi:10.1002/pnp.127.

- ↑ Brown S, Shankar R, Smith K, et al. Sensory Processing Disorder in mental health. Occupational Therapy News 2006;May:28-29.

- ↑ Russo N, Foxe JJ, Brandwein AB, Altschuler T, Gomes H, Molholm S: Multisensory processing in children with autism: high-density electrical mapping of auditory-somatosensory integration. In: Autism Res. 3. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, Oktober 2010, S. 253–67, doi:10.1002/aur.152, PMID 20730775.

- ↑ Green SA, Ben-Sasson A: Anxiety disorders and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders: is there a causal relationship? In: J Autism Dev Disord. 40. Jahrgang, Nr. 12, Dezember 2010, S. 1495–504, doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1007-x, PMID 20383658, PMC 2980623 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S: Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence. In: J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 46. Jahrgang, Nr. 12, 2005, S. 1255–68, doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x, PMID 16313426.

- ↑ Ben-Sasson A, Hen L, Fluss R, Cermak SA, Engel-Yeger B, Gal E: A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. In: J Autism Dev Disord. 39. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 2008, S. 1–11, doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0593-3, PMID 18512135.

- ↑ Williams DL, Goldstein G, Minshew NJ: Neuropsychologic functioning in children with autism: further evidence for disordered complex information-processing. In: Child Neuropsychol. 12. Jahrgang, Nr. 4–5, 2006, S. 279–98, doi:10.1080/09297040600681190, PMID 16911973, PMC 1803025 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Ross LA, Saint-Amour D, Leavitt VM, Molholm S, Javitt DC, Foxe JJ: Impaired multisensory processing in schizophrenia: deficits in the visual enhancement of speech comprehension under noisy environmental conditions. In: Schizophr. Res. 97. Jahrgang, Nr. 1-3, Dezember 2007, S. 173–83, doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.008, PMID 17928202.

- ↑ Leavitt VM, Molholm S, Ritter W, Shpaner M, Foxe JJ: Auditory processing in schizophrenia during the middle latency period (10-50 ms): high-density electrical mapping and source analysis reveal subcortical antecedents to early cortical deficits. In: J Psychiatry Neurosci. 32. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, September 2007, S. 339–53, PMID 17823650, PMC 1963354 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Rabinowicz EF, Silipo G, Goldman R, Javitt DC: Auditory sensory dysfunction in schizophrenia: imprecision or distractibility? In: Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 57. Jahrgang, Nr. 12, Dezember 2000, S. 1149–55, PMID 11115328.

- ↑ Kratz SV: Sensory integration intervention: historical concepts, treatment strategies and clinical experiences in three patients with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) deficiency. In: J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 32. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, Juni 2009, S. 353–60, doi:10.1007/s10545-009-1149-1, PMID 19381864.

- ↑ Tian YH, Cheng H: [Sensory integration function in children with primary nocturnal enuresis]. In: Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 10. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, Oktober 2008, S. 611–3, PMID 18947482 (chinesisch).

- ↑ Lane AE, Young RL, Baker AE, Angley MT: Sensory processing subtypes in autism: association with adaptive behavior. In: J Autism Dev Disord. 40. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, Januar 2010, S. 112–22, doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0840-2, PMID 19644746.

- ↑ Tomchek SD, Dunn W: Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. In: Am J Occup Ther. 61. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, 2007, S. 190–200, PMID 17436841.

- ↑ Kern JK, Trivedi MH, Grannemann BD, et al.: Sensory correlations in autism. In: Autism. 11. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, März 2007, S. 123–34, doi:10.1177/1362361307075702, PMID 17353213.

- ↑ Slobounov S, Tutwiler R, Sebastianelli W, Slobounov E: Alteration of postural responses to visual field motion in mild traumatic brain injury. In: Neurosurgery. 59. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, Juli 2006, S. 134–9; discussion 134–9, doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000219197.33182.3F, PMID 16823309.

- ↑ Bharadwaj SV, Daniel LL, Matzke PL: Sensory-processing disorder in children with cochlear implants. In: Am J Occup Ther. 63. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, 2009, S. 208–13, PMID 19432059.

- ↑ Infants and Toddlers Who Require Specialty Services and Supports. (pdf) In: Department of Community Health—Mental Health Services to Children and Families.

- ↑ ICD 10.

- ↑ APA Diagnostic Classification DSM-IV-TR | BehaveNet.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association Board of Trustees Approves DSM-5. Abgerufen am 15. Juli 2013.

- ↑ Joanne Flanagan: Sensory processing disorder. In: Pediatric News. Kennedy Krieger.org, 2009.

- ↑ a b Sensory Integration Therapies for Children With Developmental and Behavioral Disorders. Pediatrics: Official Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics

- ↑ Eagleman, David; Cytowic, Richard E.: Wednesday is indigo blue: discovering the brain of synesthesia. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass 2009, ISBN 0-262-01279-0.

- ↑ The blended senses of synesthesia, Los Angeles Times, Feb 20, 2012.

- ↑ Zamm A, Schlaug G, Eagleman DM, Loui P: Pathways to seeing music: enhanced structural connectivity in colored-music synesthesia. In: Neuroimage. 74. Jahrgang, Juli 2013, S. 359–66, doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.024, PMID 23454047.

- ↑ Cohen Kadosh R, Terhune DB: Redefining synaesthesia? In: Br J Psychol. 103. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, Februar 2012, S. 20–3, doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.2010.02003.x, PMID 22229770.

- ↑ Segal MM, Rogers GF, Needleman HL, Chapman CA: Hypokalemic sensory overstimulation. In: J Child Neurol. 22. Jahrgang, Nr. 12, 2007, S. 1408–10, doi:10.1177/0883073807307095, PMID 18174562.

- ↑ A. Jean. Ayres, Jeff Robbins: Sensory integration and the child : understanding hidden sensory challenge 25th Anniversary Edition. WPS, Los Angeles, CA 2005, ISBN 978-0-87424-437-3.

- ↑ a b Susanne Smith Roley, Zoe Mailloux; Heather Miller-Kuhaneck; Tara Glennon: Understanding Ayres Sensory Integration. In: OT PRACTICE (= 17). 12. Jahrgang, September 2007 (pediatrictherapy.com [PDF; abgerufen am 19. Juli 2013]).

- ↑ Winnie Dunn: The Impact of Sensory Processing Abilities on the Daily Lives of Young Children and Their Families: A Conceptual Model. In: Infants & Young Children: April 1997. 9. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, April 1997 (lww.com [abgerufen am 19. Juli 2013]).

- ↑ Lucy Jane Miller, Anzalone, Marie E.; Lane, Shelly J.; Cermak, Sharon A.; Osten, Elizabeth T.: Concept evolution in sensory integration: A proposed nosology for diagnosis. In: American Journal of Occupational Therapy (= 2). 61. Jahrgang, S. 135–140, doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.135 (apa.org [abgerufen am 19. Juli 2013]).