Benutzer:Kristián Czerny/Belagerung von Khartum/Karte

Ziel des Projekts ist es

- eine Karte von Khartum im Zustand während der Belagerung von Khartum zu erstellen

- und darauf aufbauend eine Karte, die die Erstürmung am 26. Januar 1885 darstellt.

Kurze Entwicklungsgeschichte[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Die Mahdisten erobern am 26. Januar 1885 Khartum und räumen in Folge die Bewohner aus den Häusern, die dann von Mahdisten bewohnt werden.

- Im August oder September 1886 wird Khartum auf Anweisung von Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, dem Nachfolger von Muhammad Ahmad, geräumt. Für den Aufbau von Omdurman werden die Gebäude in Khartum zur Materialgewinnung zertört. Khartum verkommt zu einer Ruine. Im Betrieb verblieben die Werft, die Munitionsfabrik und einige Gärten.[1][2]

- Nach Rückeroberung durch anglo-ägyptische Truppen im Jahr 1898, wurde Khartum von Grund auf neu aufgebaut.[3]

Quellen[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Primärquellen[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Karten[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

| Überschrift | Quelle | Referenzzeit | Beschreibung und Kritik |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Beispiel | 1840 | |

|

Beispiel | 1860s | |

|

Beispiel | 1860s | |

|

Beispiel | 1876 | |

|

Beispiel | 1882/1883 | |

|

Beispiel | 1883 | Beginnend vom Blauen Nil:

|

|

Beispiel | 1884 | |

|

Beispiel | 1884 | |

|

Beispiel | 1884/1885 | |

|

Beispiel | 1885-01-25 | Die Karte zeigt die Schlachtordnung einen Tag vor der Erstürmung Khartums am 25. Januar 1885. |

|

Beispiel | 1885-03-16 | |

|

Beispiel | 1885 | |

|

Beispiel | 1885/1935 |

|

|

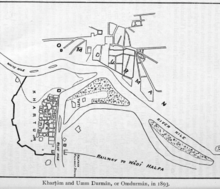

Francis Reginald Wingate: Ten years' captivity in the Mahdi's camp, 1882-1892. From the original manuscripts of Father Joseph Ohrwalder. Sampson Low, Marston & Company, London 1892 (englisch, archive.org). | 1891 | Diese Karte findet sich bei der von Francis Reginald Wingate umgeschriebenen englischen Übersetzung des Erlebnisberichts von Josef Ohrwalder über seine Gefangenschaft bei den Mahdisten, herausgegeben im Jahr 1892. Ohrwalder konnte Ende 1891 aus Omdurman fliehen und erreichte Kairo am 21. Dezember 1891. Es ist anzunehmen, dass die Karte den zur damaligen Zeit aktuellen Erkenntnisstand der anglo-ägyptischen Armee über Omdurman abbildet, da darin gemäß der Beschreibung die Kenntnisse von Ohrwalder aufgenommen wurden („revised by Father Ohrwalder“). Die deutsche Ausgabe enthält diese Karte nicht. |

|

Beispiel | 1893 | |

|

Beispiel | 1895 |

|

|

Beispiel | 1906 | |

|

Beispiel | 1908 | |

|

Beispiel | 1910 |

Weitere Karten[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Darunter sind auch modernere Karten, die Khartum nach dem Neuaufbau zeigen. Diese sind deshalb von Nutzen, da in der Sekundärliteratur die Stellen von Bauten von Altkhartum anhand von Neukhartum beschrieben werden.

- Khartoum tourist map (1963)

- Khartoum conurbation: areas subject to flood. (1965)

- Khartoum and Omdurman (1890s)

- Plan of Khartoum City (1947)

- Khartoum (1932)

- Khartoum, Omdurman and Khartoum North. (1981)

Bilder[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Literatur[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Charles George Gordon: The journals of Major-Gen. C. G. Gordon, C. B. at Kartoum: Printed from the original mss. Hrsg.: Alfred Egmont Hake. Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston 1885 (englisch, archive.org – Gordons offizielle Tagebücher vom 10. September bis zum 14. Dezember 1884 sowie Korrespondenzen an oder von Gordon.).

- Charles George Gordon: Letters of general C.G. Gordon to his sister, M.A. Gordon. Macmillan and Co., London / New York 1888 (englisch, archive.org – Briefe Gordons an seine Schwester. Der letzte Brief ist vom 14. Dezember 1884.).

- Giuseppe Cuzzi: Fünfzehn Jahre Gefangener des falschen Propheten. Nach den Mitteilungen Giuseppe Cuzzis, ehemaligen englischen Konsular-Agenten. Mit 37 Illustrationen nach Original.-Photographien. Hrsg.: Hans Resener. Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1900 (Erlebnisbericht des Autors während seiner Gefangenschaft bei den Mahdisten.).

- Josef Ohrwalder: Aufstand und Reich des Mahdi im Sudan und meine zehnjährige Gefangenschaft dortselbst. Hrsg.: Zweigverein der Leo-Gesellschaft für Tirol und Vorarlberg. Heinrich Schwick, Innsbruck 1892 (slub-dresden.de – Ohrwalders Erlebnisbericht über seine Gefangenschaft bei den Mahdisten von 1882 bis 1891. Von April 1886 bis zum Ende seiner Gefangenschaft hielt er sich zumeist in Omdurman auf.).

- Rudolph Slatin Pascha: Feuer und Schwert im Sudan. Meine Kämpfe mit den Derwischen, meine Gefangenschaft und Flucht. 1879-1895. F. A. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1896 (archive.org – Erlebnisbericht des Autors über seine Zeit im Sudan, insbesondere über seine Gefangenschaft bei den Mahdisten. Slatin hielt sich vom 14. Oktober 1884 bis zu seiner Flucht im Jahr 1895 in Omdurman bzw. in der Umgegend von Khartum auf.).

- Charles [Karl] Neufeld: A Prisoner of the Khaleeda. Twelve Years' Captivity at Omdurman. 1. Auflage. Chapman & Hall, London 1899 (englisch, archive.org – Erlebnisbericht des Autors über seine Gefangenschaft bei den Mahdisten in Omdurman von 1887 bis 1898.).

- Carl Christian Giegler: The Sudan memoirs of Carl Christian Giegler Pasha: 1873-1883. Translated from the German by Thirza Küpper. With a Foreword by the Pasha's Great-Granddaughter Heidi Groha. Hrsg.: Richard Hill (= Fontes historiae Africanae. Series Varia II). Oxford University Press, London 1984, ISBN 978-0-19-726028-9 (englisch, Giegler war von März 1879 bis Juni 1882 stellvertretender Generalgouverneur von Sudan. Er verblieb in Khartum bis zum 31. März 1883.).

- Octave Borelli: La chute de Khartoum 26 janvier 1885: Procès du colonel Hassan-Benhassaoui, juin-juillet 1887. Quantin, Paris 1893 (französisch, archive.org – Text der Anhörungen im Rahmen des Prozesses gegen Hassan Bey Bahnassawi vor einem Militärgericht, das von Juni bis Juli 1887 in Kairo stattfand. Hassan Bey, zum Zeitpunkt des Sturms auf Khartum am 26. Januar 1885 ägyptischer Kommandeur des 5. Regiments, wurde des Verrats beschuldigt. Es wurde davon freigesprochen.).

- Francis Reginald Wingate: Mahdiism and the Egyptian Sudan. Being an account of the rise and progress of Mahdiism and of subsequent events in the Sudan to the present time. Macmillan and Co., London / New York 1891 (englisch, archive.org – Enthält einen Auszug aus dem Augenzeugenbericht über die Belagerung von Bordeini Bey, einem Kaufmann in Khartum (S. 163-172), einen Auszug aus dem Report on the Soudan (1883) von J. D. H. Stewart (Appendix to Book I) und einen Auszug der Anhörungen aus dem Prozess gegen Hassan Bey Bahnassawi (Appendix to Book VI) .).

- William Hicks: The Road to Shaykan: Letters of General William Hicks Pasha written during the Sennar and Kordofan Campaigns, 1883. Hrsg.: Martin William Daly (= Occasional paper. Nr. 20). Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, University of Durham, Durham 1983 (englisch, dur.ac.uk – Das Buch enthält die Briefe von William Hicks an seine Frau vom 10. Januar bis zum 4. Oktober 1883. William Hicks wurde zum Kommandeur einer ägyptischen Expeditionsarmee ernannt, um den Aufstand der Mahdisten in Kordofan niederzuschlagen. Hicks hielt sich zur Vorbereitung der Expedition einige Zeit in Khartum auf. Seine Expedition scheiterte. Er starb am 5. November 1883 in der Schlacht von Scheikan.).

- John Colborne: With Hicks Pasha in the Soudan. Being an account of the Senaar campaign in 1883. 2. Auflage. Smith, Elder, & Co., London 1885 (englisch, Es handelt sich hierbei um ein Erlebnisbericht des Autors vom 7. Februar 1883 bis ca. Ende 1883. Colborne war in dieser Zeit Offizier in Hicks Expeditionsarmee. An der Expedition nach Kordofan nahm er nicht mehr teil. Er verließ Khartum im Juli 1883.).

- Charles William Wilson: From Korti to Khartum: A journal of the desert march from Korti to Gubat and of the ascent of the Nile in General Gordon's steamers. 2. Auflage. William Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh / London 1886 (englisch, archive.org – Es handelt sich um ein Erlebnisbericht des Autors. Er hatte das Kommando einer Vorausabteilung der Gordon Relief Expedition, die auf zwei Nildampfern nach Khartum vorstoßen sollte. Allerdings erreichte die Abteilung Khartum erst am 28. Januar 1885 und damit 2 Tage nach der Erstürmung durch die Mahdisten.).

- Muḥammad Nuṣḥī et al.: General report on the seige [sic] and fall of Khartoum. Cairo (englisch, Es handelt sich hierbei um eine Übersetzung eines Berichts über die Belagerung von Khartum, der im Juni 1885 von ägyptischen Offizieren zusammengetragen wurde.).

- Bernard M. Allen: How Khartoum Fell. In: Journal of the Royal African Society. Vol., Nr. 40.. Oxford University Press, Oktober 1941, S. 327–334, JSTOR:717439 (Ergebnisbericht über eine im Jahr 1930 durchgeführten Befragung von Augenzeugen über die Erstürmung Khartums.).

- Frank Power: Letters from Khartoum: Written during the siege. Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, London 1885 (englisch, archive.org – Briefe des Autors vom 18. Mai 1883 bis zum 31. Juli 1884. Frank Power war Journalist und kam nach Khartum, um Hicks Expedition nach Kordofan zu begleiten. Da er jedoch erkrankte, verblieb er in Khartum. Er war eines der Passagiere des Dampfers Abbas, mit dem versucht wurde aus der Belagerung von Khartum auszubrechen. Er und die weiteren Passagiere wurden am 26. September 1884 von Mahdisten getötet.).

- Martin Ludwig Hansal: Aus dem Sudan. In: Oesterreichische Monatsschrift für den Orient. 7. Jahrgang. Verlag des Orientalischen Museums, Wien 1881, S. 159 ff. (google.com – Der Autor war österreichisch-ungarischer Konsul in Khartum. Er wurde bei der Erstürmung von Khartum getötet. Tagebuchblatt vom 25. August 1881.).

- Martin Ludwig Hansal: Der Aufstand im egyptischen Sudan. In: Oesterreichische Monatsschrift für den Orient. 8. Jahrgang. Verlag des Orientalischen Museums, Wien 1882, S. 163 ff., 185 ff. (Der Autor war österreichisch-ungarischer Konsul in Khartum. Er wurde bei der Erstürmung von Khartum getötet. Tagebuchblätter vom 11. April bis 8. Oktober 1882.).

- Martin Ludwig Hansal: Der Aufstand im egyptischen Sudan (Fortsetzung). In: Oesterreichische Monatsschrift für den Orient. 9. Jahrgang. Verlag des Orientalischen Museums, Wien 1883, S. 54 ff., 94 ff., 119 ff., 196 ff. (google.de – Tagebuchblätter vom 5. November 1882 bis 12. September 1883.).

- Martin Ludwig Hansal: Der Aufstand im egyptischen Sudan (Fortsetzung). In: Oesterreichische Monatsschrift für den Orient. 10. Jahrgang. Verlag des Orientalischen Museums, Wien 1884, S. 33 ff., 84 ff., 116 ff. (google.de – Tagebuchblätter vom 16. Januar bis 5. März 1884.).

- Martin Ludwig Hansal: Der Aufstand im egyptischen Sudan (Fortsetzung). In: Oesterreichische Monatsschrift für den Orient. 11. Jahrgang. Verlag des Orientalischen Museums, Wien 1885, S. 82 ff. (google.de – Tagebuchblätter vom 21. September bis 25. Oktober 1884.).

Sekundärquellen[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Robert S. Kramer: Holy city on the Nile: Omdurman during the Mahdiyya, 1885-1898. Markus Wiener Publishers, Princeton 2011, ISBN 978-1-55876-516-0.

- Byron Farwell: Prisoners of the Mahdi. Harper & Row, New York 1967 (englisch, Eine zusammenfassende Erzählung der Erlebnisse von Rudolf Slatin, Josef Ohrwalder und Karl Neufeld über ihre Gefangenschaft bei den Mahdisten, die hauptsächlich in Omdurman stattfand.).

- Peter Clark: Three Sudanese battles (= Occasional paper. Nr. 14). Institute of African and Asian Studies, University of Khartoum, Khartoum 1977 (englisch).

- Francis Reginald Wingate: The Siege and Fall of Khartum. Reprinted from the United Service Magazine, January to July, 1892. In: Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. 13, No. 1. University of Khartoum, Khartoum 1930, S. 1–82, JSTOR:41715964 (englisch).

- H. R. J. Davies: A Rural "Eye" in the Capital: Tuti Island, Khartoum, Sudan. In: GeoJournal. Vol. 33, No. 4, August 1994, S. 387–392, JSTOR:41146238 (englisch).

- C. E. J. Walkley: The Story of Khartoum. In: Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. 18, No. 2. University of Khartoum, 1935, S. 221–241, JSTOR:41710712 (englisch).

- C. E. J. Walkley: The Story of Khartoum (Concluded). In: Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. 19, No. 1. University of Khartoum, 1936, S. 71–92, JSTOR:41716199 (englisch, Enthält Standortangaben früherer Gebäude.).

- G. Hamdan: The Growth and Functional Structure of Khartoum. In: Ekistics. Vol. 9, No. 56. Athens Center of Ekistics, Juni 1960, S. 393–398, JSTOR:43617592 (englisch).

- F. A. Edwards: The Foundation of Khartoum. In: Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. 5, No. 3. University of Khartoum, 1922, S. 157–162, JSTOR:41715629 (englisch).

- M.-A. Yagi: Les origines de Khartoum. In: Présence Africaine, Nouvelle série. No. 22. Présence Africaine Editions, 1958, S. 81–85, JSTOR:24348469 (französisch).

- R. C. Stevenson: Old Khartoum, 1821-1885. In: Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. 47. University of Khartoum, 1966, S. 1–38, JSTOR:44947302 (englisch).

- Nezar AlSayyad: Nile: Urban histories on the banks of a river. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh 2019, ISBN 978-1-4744-5862-7, CHAPTER 13 Khartoum and Omdurman: An Islamic State on the Nile in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, JSTOR:10.3366/j.ctvrxk18d (englisch).

- Seif Sadig Hassan, Osman Elkheir, Justyna Kobylarczyk,Dominika Kuśnierz-Krupa, Adam Chałupski, Michał Krupa: Urban planning of Khartoum. History and modernity Part I. History. In: Wiadomości Konserwatorskie = Journal of Heritage Conservation. Nr. 51, 2017, S. 86–94 (englisch, edu.pl [PDF]).

- Seif Sadig Hassan, Justyna Kobylarczyk, Dominika Kuśnierz-Krupa, Adam Chałupski, Michał Krupa: Urban planning of Khartoum. History and modernity Part II. Modernity. In: Wiadomości Konserwatorskie = Journal of Heritage Conservation. Nr. 52, 2017, S. 140–148 (englisch, edu.pl [PDF]).

- R.P.D. Walsh, H.R.J. Davies, S.B. Musa: Flood Frequency and Impacts at Khartoum since the Early Nineteenth Century. In: The Geographical Journal. Vol. 160, No. 3. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), November 1994, S. 266–279, JSTOR:3059609 (englisch).

- F. Rehfisch: A Sketch of the Early History of Omdurman. In: Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. 45. University of Khartoum, 1964, S. 35–47, JSTOR:41716857 (englisch).

Elemente[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Schlachtanordnung am 26. Januar 1885[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Ägypten[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Jeder Kompanie waren 150 Meter zugeteilt. 1 Btl. waren somit 600 Meter zugeteilt. Hussein Yusef Agur berichtet, dass seine Kompanie ein Stärke von 80 bis 85 Mann hatte, ergo wird es sich bei der Kompaniestärke von 105 Mann um die Sollstärke handeln. Die Soldaten des 5. Regiments waren Ägypter, die des 1. Regimentes Sudanesen. Die Offiziere waren zumeist Ägypter.

- Oberbefehlshaber der Südfront (i.e. gesamte Befestigungslinie): Farag Pascha

- westliche Hälfte (von Bahr el Abiad bis Bab el Kalakala): 5. Regiment (Oberst Hassan Bey Bahnassawi)

- (zumeist) Ägypter

- 1. Batt (Yusef Effendi Erfat) --> ganz westlich, 420 Mann (4 Komapnien a 105 Mann)

- (2. Batt) --> war in Omdurman, zweifelhaft, ob diese noch existierte

- 4. Batt. (Said Effendi Amin, kommissarisch übernommen von Farag Effendi Ali, später Ibrahim Effendi es Sudanio), 420 Mann (4 Komapnien a 105 Mann)

- Baschi-Bozuks

- Boote --> nicht separat, aus den Batt. wurden Abteilungen auf Boote geordert

- östliche Hälfte: 1. Regiment (Bakhit Bey Betraki)

- zumeist Sudanesen

- 4. Batt. (Suleiman Eff. Nashat)

- Fort (Tabia) Mukran:

- Oberbefehlshaber (direkt Gordon unterstellt): Ibrahim Effendi esh Sheikh

- 20-25 Baschi-Bozuks (Shagia-Araber)

- eine Kanonen (mit ensprechendem Personal)

- Fort (Tabia) al Kalakala:

- Baschi-Bozuks

- eine Kanonen (Krupp), nach Aussage von Ibrahim Eff. Hassanein vernahm er Schüsse von zwei Kanonen

- Nach anderer Aussage hatte Osman Bey Heshmat den Oberbefehl über das 1. Btl des 5. Reg. Hassan Bey sei administrativ, aber nicht operativ Osman Bey gegenüber weisungsbefugt gewesen zu sein?

- Abd el Kader Bey Hassan war auf einen der Befestigungen stationiert, westlich vom 1. Batt. des 5. Regimentes.

- Auf dem Blauen Nil befanden sich keine Boote, jedoch auf dem Wießen Nil.

- In der Befestigungslinie von Farag Pascha befand sich nur 1 Tor.

- Hassan Bey Bahnassawi hatte sein Posten (Hauptquartier) nahe östlich bei Bab el Kalakala. El Kalakala befand sich im letzten Drittel oder im letzten Fünftel zum Weißen Nil.

Mahmoud Agha es Said über die Aufteilung der Befestigungslinie:

- von Buri bis auf Meesalamieh: Bakhit Bey

- von Meesalamieh bis auf Bab el Kalakala: Mohammed Bey Ibrahim

- von Bab el Kalakala bis auf Bab en Nasr: Hassan Bey Bahnassawi

- von Bab en Nasr bis Bahr al Abiad: Osman Bey Hesmat

Befestigungsanlagen[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Omdurman Fort und befestigtes Lager bei Omdurman[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

-

Abb. 1: Aus dem Journal von Gordon.

-

Abb. 2: Aus dem Journal von Gordon.

-

Abb. 3: Aus dem Journal von Gordon.

Hansal

- 8. December 1882: Von dem aus Egypten nach dem Sudan delegirten Truppen-Corps sind bereits zwei Bataillone angekommen, und haben in Omdurman gegenüber Ras el Chartum ihr Lager aufgeschlagen. (56)

- 22. Februar 1884: Die weissen Soldaten (2100 Egypter ) wurden aus der Stadt in das befestigte Lager bei Omdurman delogirt und sollen successive nach Egypten abgehen. (116)

Hicks

- Friday, March 16th [1883]: I have Just returned trom my ride before breakfast. I went round the fortification they threw up the other day in the way of a long ditch and rempart when they thought the Mahdi was coming. (p. 33)

- Saturday 9th June [1883]: I have been this morning to inspect the fort I ordered to be built at Omdurman before I left for Senaar, and I am very pleased with it. [...]. The camp too out there is now clean and regularly pitched, [...]. (p. 63)

Colborne

- 1883: At Omdurman were encamped the troops which were to take part in the forthcoming campaign. (86)

„The defences on the Omdurman side consisted of Fort Omdurman, about ¾ mile from the river bank, which formed the apex of two lines of ramparts and trenches running down to the White Nile.“

„[...] Omdurman fort, a little inland from the river to the south of the White Nile bridge.“

„General Gordon ordered also Omdurman fort to be strengthened with pointed-poles the same as above described. He also ordered mines to be placed in Omdurman village after destroying the village and taking its woods for the use of the steamers. Mines were also places in the island of Tuti and in the Khor north of Omdurman.“

Nord-Fort[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

„Those at Khartoum North were centred on a double-storeyed red brick building in a wide compound, originally built as a residence, which was surrounded by trenches and converted into a fort, the “North Fort”.“

„North fort, opposite the Palace, originally a private residence [...].“

Mogrim Fort[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

„Communication with a Fort just across the White Nile at Omdurman was maintained by a signalling post at the junction of the rivers and, at high river, by a large circular fort which was built at the Mogren, on a mound and surrounded by earthworks with loopholed parapets. This fort mounted one gun and was strongly held throughout the siege.“

„Mugran, roughly on the site of the present Mugran gardens near the White Nile bridge to Omdurman [...].“

Muḥammad Nuṣḥī et al.[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Es wird erwähnt, dass Gordon am Tag seiner Ankunft in Khartum das Fort El-Makran besucht habe. (1)

Wallanlage um Khartum[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Feldschanzen (Brustwehr und Graben) um Khartum

„When General Gordon arrived in Khartoum on 18th February 1884 he found that ‘Abd al-Qädir Hilmī (Governor-General, 1882-3) had built ramparts round the town consisting of an embankment with a ditch outside it. His first inclination, as he said he had come in peace, was to level these ramparts, but the inhabitants of Khartoum begged him not to, and he agreed to leave them as they were. A short time later the Mahdist threat became so serious that he was obliged to strengthen them. The ditch was deepened and widened so that it could not be crossed, becoming, according to some people, 18 feet deep in places. The soil from the ditch was piled up in the form of a high rampart on the inner side of it, the crest of this rampart being levelled off and having a loopholed mud wall about five feet high built along the top of it. Wire entanglements were erected about 100 yards beyond the ditch and, outside these, land mines were laid and “crows’ feet” (caltrops) scattered about [...].“

„No ramparts or earthworks were erected on the White Nile side of the town between Fort Mogren and the end of the defence perimeter on the White Nile, this sector being regarded as adequately protected by the river, the Omdurman Fort, and troops on the river.“

„The main fortifications ran round the town in a semi-circle from this point on the White Nile to a point on the Blue Nile approximately where the Blue Nile bridge is now situated. The perimeter varied in length from about 4⅓ miles at high Nile to nearly 5⅔ miles at low Nile. The west end of it was defended, in the early days of the siege, by two steamers and later by two barges, each mounting a gun and manned by an officer and twenty-five men.“

„The line of the old fortifications, now levelled, can still be followed since it is indicated on some of the present street-plans. The name “Gordon’s ramparts’ is marked on the ground where the line cuts the eastern end of the two streets Sharia El Gamaa and Sharia El Gamhoria. Part of the road between these points and the railway station follows the rampart line.“

„The fortifications of Khartoum were a mile or two from the town. They were first built by a previous Governor General, and Gordon set about repairing them. A ditch, three metres deep and four metres wide, was constructed with a parapet on the town side. The line of fortifications went from thé Blue to the While Nile.“

„The parapet followed the railway line roughly (one or two small capstans still exist marking the site of the line of Gordon’s ramparts) [...].“

Muḥammad Nuṣḥī et al.[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- The fire [field?] fortifications' lines were about 7,000 meters long at a full Nile, and about 91000 metres at a low Nile, and began from the Blue Nile to the White Nile. (5)

- The defeat of Hicks Pasha's army has prevailed at that time in Khartoom, therefore the gates of El Kalakla and Burri were locked, and only the gate of El Musallamieh was kept open[...]. (6)

- therefore he [Gordon] ordered that the two gates of Burri and Kalakla to be closed and to be inside of the fortifications. The gate of Musallamiah was the only gate left opened, but strongly fortified, [...]. (13-14)

- Abd el Kadir Pasha the previous Governor General of the Soudan had made a large quantity of crows' feet to be put before the fortifications for preventing the enemy of dashing forward, therefore Gordon Pasha ordered that all those crows' feet should be thrown about in different places outside the fortifications [...].

Hansal[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 25. August 1881: Die Stadt Chartum befindet sich in völlig vertheidigungslosem Zustande. Nach der Südseite hin frei und offen, kann ein Landsturm unbehindert einmarschiren. Wir haben gestern dem Pascha die Vorstellung gemacht, dass man ausserhalb des Stadtrayons wenigstens Schanzgräben aufwerfen sollte, wenn man keine Forts errichten will. (161)

- 1. Juli 1882: Endlich hat man begonnen, zum Schutze der Stadt Chartum Vertheidigungswerke anzulegen, welche das Terrain im Süden der Stadt vom Blauen bis zum Weissen Flusse mit Kanonen bestreichen und einen Landsturm aufhalten können. (187)

- 8. August 1882: Chartum ist im Belagerungszustand. Fünf Forts, je mit einer Kanone und einem Piquet Infanterie armirt, beherrschen die Umgebung. Die Stadt ist mit Cordons in Distanz von je 100 Schritten umsäumt. [...] Abd-el-Kader Pascha hat zur grösseren Sicherheit auch angeordnet, dass die beiden Flüsse im Hintergrunde der Stadt durch einen 7 M. breiten und 4 M. tiefen Canal mit einander verbunden und die Arbeiten sofort in Angriff genommen werden, um Chartum zu isoliren, [...]. (188)

- 28. September 1882: Die 5 vereinzelten Erdwerke ausserhalb des Stadtrayons von Chartum, je mit einer Kanone und 20 Flinten armirt, können einen Massenansturm nicht aufhalten; entweder es muss die Idee, die Stadt durch einen Canal in eine Inselfestung zu verwandeln, sofort zur Ausführung gelangen, oder es müssen die Forts durch Schanzgräben von einem Flusse zum andern in Zusammenhang gebracht werden. Würde der Mahdi in der nächsten Zeit kommen oder nur einen Theil seiner Legionen schicken, dann wäre Chartum verloren. (189)

- 8. December 1882: Am 15. November wurden endlich die projectirten Canalarbeiten im Süden unserer Stadt in Angriff genommen und sind bereits der Vollendung nahe. Emsiges Treiben herrschte unter den tausend Arbeitern, die Parcellen waren mit einer unabsehbaren Reihe von Fahnen abgesteckt, Zelte warea aufgestellt und die Militärmusik animirte die Beschäftigten. Durch diese 5100 Meter lange Verbindungsader der beiden Ströme eine Meile oberhalb ihrer Vereinigung bildet der Stadtrayon Chartum eine Inselfestung. Die Erdaushebungen wurden auf die Haussteuer repartirt und daher von den Stadtbewohnern besorgt, wonach die Landesregierung keinen Beitrag zu leisten hatte; die europäische Colonie hat, wie seinerzeit mitgetheilt wurde, für das gemeinnützige Werk 1000 Thaler beigesteuert, wovon die Brücken hergestellt werden sollen. Der Canal umsäumt die im Juli errichteten fünf Forts und bildet in dem jetzigen Massstabe von fünf Meter Breite und drei Meter Tiefe vorläufig einen Schanzgraben zur Sicherheit der Stadt; später soll er für die Navigation verbreitert und vertieft werden. (55-56)

Giegler[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 1882: Abd al-Qadir became very active in Khartoum and fortified the town. All citizens rich and poor had to help him so that a large part of the ditch, a section four kilometres long, was already completed when I returned to Khartoum [2. Juni 1882]. [...] I undertook the supervision of the works still to be completed in the fortifications of the town. The last stretch which led to the White Nile was difficult. It was the weakest link, and it was from there that the Mahdists were later to penetrate the town. (210-211)

Colborne[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- 1883: Khartoum, [...], stands, [...], on the Blue Nile, its other three sides being surrounded by ill-constructed, clumsily-built ramparts of mud, without the least attempt at military engineering. (81-82)

Power[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- New Year's Day, 1884: To show how much the Khedive knows of the place, he telegraphs to Colonel de Coëtlogon to ask — are the gates closed ? as if the place had walls. It is an open town, with garden, fields, &c., and not a bit of defence round it till Colonel de Coetlogan commenced the ditch [...]. (68)

- January 2, 1884: We have paved the bottom of the ditch and side of the fortification with spear-heads, and have for 100 yards the ground in front strewn with iron " crows' feet," things that have three short spikes up however -they are thrown and then beyond, for 500 yards, broken bottles (you know the Mahdi's men are all in their bare feet); at intervals we have put tin biscuit-boxes full of powder, nails, and bullets, at two feet under ground, with electric wires to them, so Messieurs the rebels will have a mauvais quart d'heure before they get to the ditch. (69-70)

Anhörung von Mikhail Daud Bey[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Es gab es drei Tore:

- Bab el Messalamieh,

- Bab Buri und

- Bab el Kalakala.

- Die Befestigungen wurden von Abd el Kader Pascha errichtet. Gordon ließ den Graben um einen halben Meter erweitern und "made a wall inside them and barracks"(?).

Anhörung von Said Effendi Amin[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Westlich vom Tor Bab el Kalakala gab es eine Befestigung

- Der Graben war 3 meter tief und 4 Meter breit, zumindest ab Bab el Kalakala bis zum Weißen Nil

- Am Tag der Erstürmung war der Graben durch Regen und der Nilüberflutung in einem schlechten Zustand. Hin zum Weißen Nil war der Graben lediglich 2 Meter tief.

Anhörung von Hussein Yusef Agur[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Östlich vom Tor Bab el Kalakala gab es eine Befestigung

Fort und Tor Burri[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

„During an inspection along the line General Gordon found the fort of Burri was unfit for soldiers and ordered Bimb. Khalil Ef. Fouzi Lo. and Stewart Pasha to build another big fort in that place and he also strengthened and made higher the wall of the line of Fortifications 20 centimetres higher than before making necessary loop-holes for each soldier.“

„By this time the Nile had become low and the water of the Blue Nile became over 30 metres distant from the fort of "Burri" leaving a suitable ground for the enemy to attack - so General Gordon saw that this ground was to be fortified and he ordered that the trench should be extended as far as the water and that a chain of iron should connect the (khandaj) trench with the opposite shore and boats be placed close to each other in the water tied to that chain which boats were to be filled with mines which would take fire from mere touch. Also a banquet to be made from the Fort to Nile water; then at the fort of the "Show Salka" to place dynamic works.“

„There was only one other bastion between this [Fort Masallamīyya] and the eastern end of the line, and this was of much the same pattern as the Kalākla Fort.“

„The eastern end itself was defended by Burri Fort, which resembled the Mogren Fort and was situated inside the ramparts about 325 yards from the Blue Nile at low river (in the present University grounds). The Burri Fort and the eastern sector was under the command of Bakhit Bey Batrākī. Near the Burri Fort was a small gap through the defences known as the Burri Gate, which was kept closed from the earliest days of the siege.“

„It [i.e. the line of fortifications] started near the present Blue Nile Bridge and a gate, the Burri gate, was the exit for the villages of the Blue Nile. There was also a Burri fort, the site of which is in the University grounds.“

Fort (Tabia) und Tor (Bab) al Masallamīyya[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

„The largest and most important bastion in the defences, known as the Masallamīyya Fort (which was situated just east of the present railway station) was strongly held by a force under the immediate command of Faraj Pasha Muhammad al-Zainī [...] who was in supreme command of the whole line of defences and had his headquarters in or near it. A few yards east of this bastion was the Masallamīyya Gate, the main passage through the fortifications, which consisted of a gap in the ramparts, flanked by walling and closed by an iron gate, which could be lowered like a drawbridge over the ditch by means of winches. It was through this gate that the garrison made its sorties and that outsiders were admitted into the town.“

„The Messelamia gate [...] was built of burnt bricks and cement.“

„The level-crossing to the east of Khartoum Central Railway station is still called by the natives "Bab Messelemia".“

„[...] after 3,000 metres, a little to the east of the present railway station, was another gate, the Masallamiya gate. (Masallamiya is an old town near Wad Medani.) By it was a second fort.“

Fort (Tabia) und Tor (Bab) al Kalākla[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

„On the perimeter due south of the town was a large bastion named the Kalākla Fort. (Its site was just south of the present Ḥurrīyya Bridge.) This bastion was strongly garrisoned by a force under the command of Ḥasan Bey al-Bahnasäwi who was in charge of the western sector of the defences. East of the bastion, and probably quite close to it, was a narrow passage through the fortifications known as the Kalākla Gate. This passage was chiefly used by people bringing in milk and other produce. It was closed as soon as the news of the Hicks débâcle of 1883 reached Khartoum, opened by General Gordon, but closed again in the early days of the siege.“

„Nothing remained gate, but the site of the Kalakala gate can be seen where the Gebel Aulia road cuts through the line of the earthwork.“

„Following the railway again [from Masallamīyya], 1,500 metres further on was the third gate, the Kalakla gate. (Kalakla is a village on the road to Jahal Aulia). The site of this gate is the Hurriya bridge over the railway on the road to Shajara. There was another fort a little to the west [...].“

Fort (Tabia) und Tor (Bab) al Nasr[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Anhörung von Mahmoud Agha es Said[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Es wird ein Bab en Nasr (an anderer Stelle Nasr Bey) erwähnt Tor oder Fort? Dabei werden in den meisten Quellen nur drei Tore angegeben. Nei Nushi wird ein Nasr Bey erwähnt, Kommandant der Kavallerie.

Brustwehren auf der Insel Tuti[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Siedlungen[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- ↑ R. C. Stevenson: Old Khartoum, 1821-1885. In: Sudan Notes and Records. Vol. 47. University of Khartoum, 1966, S. 33, JSTOR:44947302 (englisch).

- ↑ Robert S. Kramer: Holy city on the Nile: Omdurman during the Mahdiyya, 1885-1898. Markus Wiener Publishers, Princeton 2011, ISBN 978-1-55876-516-0, S. 26–27.

- ↑ Seif Sadig Hassan, Osman Elkheir, Justyna Kobylarczyk,Dominika Kuśnierz-Krupa, Adam Chałupski, Michał Krupa: Urban planning of Khartoum. History and modernity Part I. History. In: Wiadomości Konserwatorskie = Journal of Heritage Conservation. Nr. 51, 2017, S. 92 (englisch, edu.pl [PDF]).