Benutzer:Bk1 168/Übersetzungen/John Forester

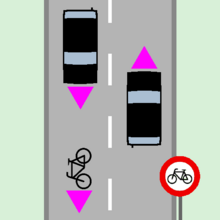

John Forester (* [[1929]) ist ist ein US-amerikanischer Verkehrsingenieur, der sich auf Radverkehr (Englisch "bicycle transportation engineering") spezialisiert hat. Er ist auch ein vielbeachteter Fahrradaktivist, der sich für Radfahrer und deren Rechte, die Straßen zu benutzen, engagiert hat. Bekannt ist er als "Vater des Vehicular Cycling"[1] und für das Erstellen des Programms Effective Cycling zum Training des verkehrsgerechten Radfahrens. Er hat auch ein Buch mit demselben Titel geschrieben. Er hat den Begriff des "Vehicular Cycling Principle" geprägt: Radfahrer fahren am besten, wenn sie sich als Fahrer eines Fahrzeugs verhalten und so behandelt werden. Zu den von ihm veröffentlichen Büchern gehört auch Bicycle Transportation: A Handbook for Cycling Transportation Engineers.[2]

Frühes Leben[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

John Forester wurde in East Dulwich in London in England geboren. Er ist der ältere Sohn des Schriftstellers C. S. Forester und seiner Frau Kathleen. Die Familie zog im März 1940 nach Berkeley. Dort besuchte er die öffentlichen Schulen zunächst in Kalifornien und später an der amerikanischen Ostküste. Seine Eltern wurden geschieden. Als er die Schule beendet hatte, studierte er an der University of California at Berkeley[3] zunächst Physik und später Englisch und erlangte im August 1951 einen Abschluss als Bachelor. Nach einer kurzen Zeit in der U.S. Navy in den frühen 1950er Jahren während des Koreakriegs ließ sich Forester schließlich in Kalifornien nieder und wurde, was er selbst "ndustrial engineer",[4] "senior research engineer", ein Professor und vor allem ein Experte der Wissenschaft des Radfahrens.[3]

In April 1966, Forester's father died. The unexpectedly large estate, its contents, and its disposition proved to Forester that his father, whom he had loved and admired, had consistently lied to him for years, and strongly suggested evidence of another secret life. That discovery was a traumatic experience, and led to his two-volume biography of his father, Novelist and Story Teller: The Life of C. S. Forester.[5][6]

Cycling advocacy[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

From early childhood, Forester had been a passionate cyclist.[3] Forester first became a cycling activist in 1971, after being ticketed in Palo Alto, California for riding his bicycle on the street instead of on a recently legislated separate bikeway for that section of the street, the sidewalk. He contested the ticket and eventually the city ordinance was overturned.[7] His first published article—the first of his many publications on alternatives to bikeways over the following four decades—appeared in the February 1973 issue of Bike World, a regional Northern California bimonthly magazine.[8]

In May 1973, his focus broadened as the Food and Drug Administration (later the Consumer Product Safety Commission, or CPSC) issued extensive product safety regulations for bicycles. Originally intended only for children's bicycles, the regulations were soon expanded to include all bicycles except for track bikes and custom-assembled bicycles. In October of that year, Forester published an article in Bike World denouncing both the California Department of Transportation and the CPSC.[9] He targeted the new CPSC regulations, especially the "eight reflector" system, which required front, rear, wheel and pedal reflectors. The front reflector is placed at the location for a bicycle headlight, which it replaces. However, motor vehicle drivers who are about to cross the path of the cyclist would not see the approaching cyclist because the headlights of their motor vehicle do not shine onto the front reflector of the bicycle, often resulting in a crash. (Only if the bicycle is directly in front of the car and only if the bicycle is headed the wrong way, will the car's headlights illuminate the bicycle's front reflector, until the inevitable head-on crash.)

After the rules were finalized, Forester sued the CPSC. Acting as his own lawyer (pro se), Forester did not understand that United States federal law did not grant jurisdiction to the appeals court to review the technical merit of the rules (a so-called "de novo" review) unless the procedure used to create the rules was flawed. The CPSC argued that a challenger must prove the process was "arbitrary and capricious." The judge ordered a de novo review of the rules; threw out four of them, but left the "eight reflector" standard untouched.[10] Forester, emboldened by this partial success, proceeded to launch further challenges to administrative rules in court, but did not duplicate that early success. His legal advocacy remains highly controversial.[11][12]

In addition to legal advocacy, Forester is known for his theories regarding cycling safety.[13] His Effective Cycling educational program, developed subsequent to his research claiming that integrating motorists and educated cyclists reduces accidents more than creating separate bicycle lanes, was implemented by the League of American Bicyclists (formerly, the League of American Wheelmen) until Forester withdrew his permission for that organization to use the name.[13]

Bibliographie[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Statistical Selection of Business Strategies Chicago, Richard D. Irwin, 1968 Lib Cong 67-17054

- Bicycle Transportation (First edition, 1977; Second edition 1994, The MIT Press, Vorlage:ISBN)

- Effective Cycling (First edition, 1976; Sixth edition, MIT Press, 1992, Vorlage:ISBN), 7th (2012) Vorlage:ISBN

- Effective Cycling Program, Effective Cycling Instructor's Manual, the film Bicycling Safely On The Road (Iowa State University, 1978)

- Effective Cycling, The Movie, (Seidler Productions, 1992)

- Novelist & Story Teller, The Life of C. S. Forester. Lake Oswego, OR: eNet Press, 2013. Ebook reprint of self-published (2000) two-volume biography of his father.

See also[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

References[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

External links[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- John Forester's web site

- ProBicycle biography of John Forester

- John Forester talk at Google headquarters, May 17, 2007 auf YouTube (video)

- Effective Cycling: The Cure for Un-riding! Review by Cycle California! Magazine.

[[Category:American male cyclists]]

[[Category:English emigrants to the United States]]

[[Category:1929 births]]

[[Category:Living people]]

[[Category:Vehicular cycling]]

[[Category:People from the London Borough of Southwark]]

[[Category:Cycling advocates]]

- ↑ Christie Aschwanden: Bikes and cars: Can we share the road? In: Los Angeles Times, November 2, 2009. Abgerufen im 22 July 2014 „Forester is the father of the "vehicular cycling" movement -- a philosophy that views the bicycle as a form of transportation that belongs on the streets alongside cars.“

- ↑ John Forester: Bicycle Transportation: A Handbook for Cycling Transportation Engineers. Second Auflage. MIT Press, Preface 1994, ISBN 978-0-262-56079-5, S. 6: „This book is the third form of my book on cycling transportation engineering. A first version appeared under the title of Cycling Transportation Engineering Handbook (Custom Cycle Fitments, 1977), and the first formal edition was Bicycle Transportation (The MIT Press, 1983).“

- ↑ a b c Referenzfehler: Ungültiges

<ref>-Tag; kein Text angegeben für Einzelnachweis mit dem Namen history. - ↑ State of California, Department of Consumer Affairs: In: Board of Professional Engineers, Land Surveyors and Geologists.

- ↑ John Forester: Novelist & Storyteller: The Life of C. S. Forester. first Auflage. John Forester, Lemon Grove, CA 2000, ISBN 978-0-940558-04-5.

- ↑ John Forester: Novelist & Storyteller: The Life of C. S. Forester. second Auflage. eNet Press, Lake Oswego, OR 2013, ISBN 978-1-61886-004-0 (google.com [PDF; abgerufen am 23. Juli 2014]).. Publisher's excerpt

- ↑ Jeff Mappes: Pedaling Revolution: How Cyclists Are Changing American Cities. Oregon State University Press, Portland, OR 2009, ISBN 978-0-87071-419-1, 41–42 (archive.org).

- ↑ John Forester: What about Bikeways? In: Bike World. Februar 1973, ISSN 0098-8650, S. 36–37.

- ↑ John Forester: Toy Bike Syndrome. In: Bike World. Oktober 1973, ISSN 0098-8650, S. 24–27.

- ↑ Forester v. Consumer Product Safety Commission. In: 559 F. 2d 774 - Court of Appeals, Dist. of Columbia Circuit 1977. Abgerufen am 27. November 2013.

- ↑ Bruce Epperson: The Great Schism: Federal Bicycle Safety Regulation and the Unraveling of American Bicycle Planning. In: Transportation Law Journal. 37. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, 2010, ISSN 0049-450X, S. 73–118 (du.edu [PDF; abgerufen am 22. Juli 2014]).

- ↑ John Forrester: Letter to the Editor: Review of the Great Schism. In: Transportation Law Journal. 39. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 2011, ISSN 0049-450X, S. 31–51 (du.edu [PDF; abgerufen am 22. Juli 2014]).

- ↑ a b Smith, David. The bicycle driver. Cranked Magazine #5, pp. 22–25. Accessed November 1, 2007.