Benutzer:Shi Annan/Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

Vorlage:Short description Vorlage:Use dmy dates Vorlage:Infobox collection

The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art includes 28,000 objects documenting Islamic art over a period of almost 1400 years, from 700 AD to the end of the twentieth century. It is the largest of the Khalili Collections: eight collections assembled, conserved, published and exhibited by the British-Iranian scholar, collector and philanthropist Nasser David Khalili, each of which is considered among the most important in its field.[1] Khalili's collection is one of the most comprehensive Islamic art collections in the world[2][3][4] and the largest in private hands.[5][6][7]

In addition to copies of the Quran, and rare and illustrated manuscripts, the collection includes album and miniature paintings, lacquer, ceramics, glass and rock crystal, metalwork, arms and armour, jewellery, carpets and textiles, over 15,000 coins, and architectural elements. The collection includes folios from manuscripts with Persian miniatures, including the Great Mongol Shahnameh, the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, and the oldest manuscript of world history the Jamiʿ al-tawarikh. Among its collections of arms and armour is a 13th-century gold saddle from the time of Genghis Khan.

The ceramic collection, numbering around 2,000 items, has been described as particularly strong in blue and white pottery of the Timurid era and also pottery of pre-Mongol Bamiyan. The jewellery collection includes more than 600 rings. Around 200 objects relate to medieval Islamic science and medicine, including astronomical instruments for orienting towards Mecca, tools, scales, weights, and "magic bowls" intended for medical use. Among the scientific instruments are a celestial globe made in 1285–6 and a 17th-century astrolabe commissioned by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan.

Exhibitions drawing exclusively from the collection have been held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris and the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam as well as at many other museums and institutions worldwide.[8] An exhibition at the Emirates Palace in Abu Dhabi in 2008 was, at the time, the largest exhibition of Islamic art ever held.[6]

The Wall Street Journal has described it as the greatest collection of Islamic Art in existence.[2] According to Edward Gibbs, Chairman of Middle East and India at Sotheby's, it is the best such collection in private hands.[3]

Khalili Collections

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Based in the UK and originally from Iran, Nasser David Khalili has assembled eight distinct art collections, each considered among the most important in its field.[1] In total, they include 35,000 objects.[9] He began collecting Islamic art in 1970.[10] Private collections usually focus on either collecting complete series of objects or on selecting those of the highest aesthetic quality; Khalili's collection combines both traditions.[4] The collection of Islamic art is one of two focused on Islam, along with the Khalili Collection of Hajj and the Arts of Pilgrimage. Islamic enamels also appear in the Khalili Collection of Enamels of the World.[11] While collecting Islamic art, Khalili encountered damascening, in which gold and silver decoration is pressed into an iron surface; this led him to acquire a separate collection of Spanish damascened metalwork.[12]

In addition to collecting, conserving, publishing and exhibiting the collection, Khalili has funded the creation of a research centre in Islamic art at the University of Oxford[13][14] as well as the first university chair in the subject, at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.[15] His own publications include a history of Islamic art and architecture which has been published in four languages.[16] Khalili has described Islamic art as "the most beautiful and diverse art".[3] His stated aim is to use art and culture "to create good will between the West and the Muslim world."[17]

Objects in the collection

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Qurans

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

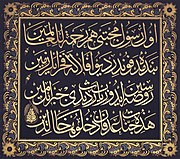

The collection of complete Qurans and individual folios includes 98 from before 1000 AD,[18] 56 from 1000 to 1400,[19] 60 from 1400 to 1600,[20] and more than 150 from after 1600.[21] It was described by the historian Robert Irwin as "one of the largest and most representative collections of Quranic manuscripts in the world"[22] and is the largest private collection.[23] Among the earliest objects in the collection are some complete examples with their original bindings.[18] The collection has an individual folio from the Codex Parisino-petropolitanus, one of the very oldest surviving Quran manuscripts.[24] There are two folios from the 10th-century Blue Quran, the only surviving Quran on indigo-dyed vellum.Vorlage:Sfn[25] A section of a 13th-century Quran bears the signature of calligrapher Yaqut al-Musta'simi, regarded as one of the greats of classical Quranic calligraphy.Vorlage:Sfn An exceptionally large single-volume Quran dated to 1552 AD was in the Mughal imperial library during the reigns of Aurangzeb and Shah 'Alam, bearing their seals. It is thought to have been commissioned by Shah Tahmasp.Vorlage:Sfn An 18th-century single-volume Quran, the work of calligrapher Mahmud Celaleddin Efendi, was previously owned by Ottoman princess Nazime Sultan.Vorlage:Sfn

Illustrated manuscripts and miniature paintings

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

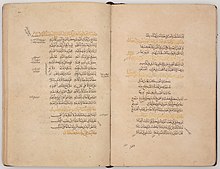

The illustrated manuscripts in the collection include complete copies and detached folios from Iran, India and Turkey. There are several complete exemplars or folios of the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), the national epic poem of Iran, whose text and illustrations combine historical and mythical material.[26] These include ten illustrated folios from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp (circa 1520),[27] four from the late 16th century Eckstein Shahnameh,[28] and one of 57 surviving folios of the Great Mongol Shahnameh (circa 1330s).Vorlage:Sfn

There are several exemplars of the Khamsa of Nizami, which comprises five epic poems.[29] A diwan (volume of collected poetry) of the 14th-century poet Hafez is dated AH 924 (1567–8 AD) with illuminated two paintings.[29] Among many detached folios from Iran, especially 17th-century Isfahan, are works by Reza Abbasi, Mo'en Mosavver, Mohammad Zaman, Aliquli Jabbadar, and Shaykh 'Abbasi.[29] A 15th-century exemplar of the Masnavi, a poem by the scholar and mystic Rumi, is illuminated in ink, watercolour, and gold.Vorlage:Sfn The folios from 15th-century Ottoman Turkey include two from a Siyer-i Nebi (a biography of Prophet Muhammed) commissioned by Sultan Murad III.[29] Some folios are from works of dynastic or global history, including two from the earliest surviving illustrated exemplar of the Zafarnama by Sharaf ad-Din Ali Yazdi, from 1436 AD.[30] There is a section from the oldest manuscript of the Jami' al-tawarikh, Rashid al-Din's world history; the other surviving section of the same manuscript is in Edinburgh University Library.[31] A painting from the Padshanamah (chronicle of the king's reign) shows Shah Jahan, with family and courtiers, watching two elephants fighting.Vorlage:Sfn

Among the 76 Indian paintings are many commissioned by the Mughal emperors. They include two folios from a Ramayana that Akbar commissioned for his mother and one folio from the Akbar Hamzanama, a large illustrated manuscript of the Hamzanama also commissioned by Akbar.[32] There are two illustrated folios from the autobiography of Babur, founder of the Mughal Empire.[32]

Other manuscripts

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Other manuscripts include a lavishly illuminated exemplar of part one of Al-Shifa bi Ta'rif Huquq al-Mustafa (a detailed commentary on the life and character of Muhammed) from the 17th-century Moroccan royal court.Vorlage:Sfn A manuscript of Tuhfah al-Saʿdiyyah, a commentary on Ibn Sina's medical text The Canon of Medicine, dates from the 14th century.Vorlage:Sfn A 14th-century diwan of the poet Al-Mutanabbi is illuminated to the highest standards of that period.Vorlage:Sfn

Calligraphy

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The 174 items of calligraphy[33] include hilyes (verbal portraits of the Muhammed), ijazat (licences allowing the holder to transmit protected knowledge), muraqqa'at (albums of calligraphy), and siyah mashq (calligraphic practice sheets).[34] The calligraphers include Yaqut al-Musta'simi, known for refining and codifying six basic calligraphic styles of Arabic script,[35] and others influenced by him,[34] as well as the Sultans Abdulmejid I and Mahmud II.[33] The bulk of the collection comes from Ottoman Turkey from the 17th to the 19th centuries.[34] One album of calligraphy contains pieces signed by the scribes of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.[36]

Metalwork

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The 1,000 metalwork objects in the collection cover the period from the 6th century to the early 20th century. They come from across the Islamic world, especially Iran, the Jazira (in present-day Syria and Iraq), and 17th- and 18th-century India.[37] The objects include bowls, incense burners, and ewers.Vorlage:Sfn Brass and bronze are common materials.Vorlage:Sfn Metalworkers in 12th- and 13th-century Iran made vessels and incense burners in the shape of birds and animals, and the collection includes several examples.Vorlage:Sfn The objects' decorations range from arabesque patterns to inscriptions and to figurative art.Vorlage:Sfn

Although it is rare in Islamic metalwork for artists to sign or date their pieces, several objects in the collection have signed names or dates.[37] Some bear the names of patrons;[37] for example, a 14th-century silver-inlaid brass bowl bears the name of Al-Nasir Muhammad, a 13th-century Mamluk Sultan.Vorlage:Sfn A brass casket from early 13th-century Jazira, lavishly inlaid with silver, has four numeric dials; these formed part of a combination lock whose mechanism is now missing.Vorlage:Sfn

Jewellery

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]The jewellery in the collection numbers almost 600 personal adornments,[38] plus more than 600 rings[39] and 200 luxury items from the royal workshops of the Mughal Empire.[40] Together this is the most comprehensive published collection of Islamic jewellery.[38] The adornments include almost every kind—from bracelets and amulets to buttons and brooches—from the 7th century onward. They are decorated with gems, enamel, or niello.[38] The collection's Fatimid objects have the "rope and grain" filigree style characteristic of Egypt or Syria.[38] The Mughal objects include a ruby engraved with the names of emperors Shah Jahan and Jahangir.[40] A box from 17th-century Mughal India consists of 103 engraved emeralds in a gold frame, topped by a faceted diamond.Vorlage:Sfn Most of the enamelled gold objects made for the Mughal court are now in the Iranian crown jewels or in the Hermitage Museum in Russia; an exception is an octagonal box in the Khalili collection that dates from around 1700.Vorlage:Sfn A hookah bowl from 18th-century Mewar in India is made of gold with colourful enamel decoration.[41] A gold badge, collar and star, constituting the Order of the Lion and the Sun, is decorated with enamels and precious stones. It was presented by Fath-Ali Shah Qajar of Iran to the British diplomat John Macdonald Kinneir.[42]

Very few Islamic rings had been documented before Khalili published his collection of 618.[39] Whereas some rings are purely decorative, many function as signet rings while others have religious inscriptions intended to give protection to the wearer.[43][44] Art historian Marian Wenzel used the collection as the basis for a typology of Islamic rings.[39]

-

Emerald-set box, Mughal India, c. 1635

-

Stirrup ring, Fatimid Egypt or Syria, 11th–12th century

-

Button, southern Spain, 14th–15th century

Arms and armour

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The collection's arms and armour range from the 7th century to the 19th. There are belt fittings that express military rank,Vorlage:Sfn and multiple chanfrons (masks for protecting horse's faces).[45] Two sets of horse trappings from the 13th and 14th centuries include a complete gold saddle.Vorlage:Sfn[45] A 15th-century iron and steel war mask is decorated with engravings.Vorlage:Sfn Describing the arms and armour catalogue, James W. Allan, Professor of Eastern Art at the University of Oxford, wrote "The range of pieces [...] is quite extraordinary: a 1.8 m long seventeenth-century Indian cannon, Turkish and Persian daggers with astonishingly beautiful enamelled handles and scabbards, gold fittings for a 10th-century Chinese saddle, a Moroccan horse-shoe etc."[46]

Seals and talismans

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The seals and talismans number more than 3,500, forming the largest such collection in the world. Many of these are set in rings or pendants or mounted on bases. The materials include metals, precious or semi-precious stones, and clay.[47] They are inscribed with a variety of religious phrases and texts, in languages including Arabic, Persian, Hebrew, Turkish, and Latin.[47] The seals bear the names and titles of the officials who used them. These include the seals of the 14th-century ruler Qara Mahammad, and of the Safavid rulers Tahmasp I and Suleiman.[48] The seal of the 19th-century Ottoman Sultan Abdulaziz renders his tughra (official monogram) in brass.[49]

Textiles

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The more than 250 textiles include embroideries, carpets, and costumes from the 6th to the 19th centuries.[50] The carpets come from royal workshops across the Islamic world.[50] Other textiles include Ottoman and Safavid gold brocades and woven silks from Mughal-era and Sultanate India. The costumes include shawls from Kashmir, talismanic shirts, and ikat coats.[50] The 16th-century Ottoman court used European textiles as robes of honour, later creating its own looms to control production.Vorlage:Sfn Some of the collection's textiles have explicitly religious purposes: a North African silk panel repeats the name of Allah hundreds of times and a carpet was used as a mihrab (prayer niche).Vorlage:Sfn The Dhulfaqar, a double-bladed sword said to have been taken in the battle of Badr, is a motif appearing on two Ottoman banners.Vorlage:Sfn

Lacquer

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The lacquered objects, numbering more than 500, document the evolution of Islamic lacquer from the 15th to the 19th century. They show the influence of China in the early period and of Europe in the 19th century.[51] Almost every known lacquer painter in the Islamic world is represented in the collection, along with some previously unknown. The notable artists include Mohammad Zaman and Mohammad Sadiq.[51] The collection's lacquered pen box by Mo'en Mosavver is the only one he is known to have painted.Vorlage:Sfn A 19th-century pen box, Vorlage:Convert long, was commissioned by Mohammad Shah Qajar for his official Manouchehr Khan Gorji, commemorating the latter's battle against Bedouins. It depicts the battle with densely-packed scenes and describes it in Persian text.Vorlage:Sfn An 18th-century instrument case depicts the Adoration of the Magi, and on the other side, a woman in heroic pose.Vorlage:Sfn

Ceramics

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Ceramic styles popular in the Islamic world include lustreware (with a thin metallic film), sgraffiato (in which the design is etched into the slip), and underglaze pottery.Vorlage:Sfn Khalili's ceramic collection, numbering nearly 2,000 items, has been described as particularly strong in pottery of the Timurid era and also that of pre-Mongol Bamiyan.[52] As well as bowls, plates, and vases, the ceramics include figurines as well as decorative tiles of the sort used in religious and secular buildings.Vorlage:Sfn It includes the earliest known dated ceramic from Iran: a signed fritware bottle dated to 1139–40.[53] Other unique items include a bowl with a depiction of a Buraq, a four-legged creature that is said to have borne Muhammad from Mecca to Jerusalem and then to heaven.[53][54] Laqabi-wares are deeply carved ceramics usually depicting animals or birds; the collection has a Syrian example from around 1200 AD.Vorlage:Sfn The wares from 15th-century Iran and central Asia illustrate the connections between Chinese and Islamic pottery. Other collections have a scant coverage of this period.[55]

Glass

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

More than 300 objects in the collection illustrate the history of Islamic glass, going back to the Sasanian and Byzantine Empires.[56] Egyptian and Syrian glassmakers of the 13th and 14th centuries made lavishly decorated enamelled and gilded glassware which was in demand for export, and the collection's objects cover this period. Some of these were commissioned by the Mamluk Court for mosques, and the collection includes one created for the 14th-century Sultan Barquq,[57] decorated with his heraldic roundel.Vorlage:Sfn Some objects are mould-blown, and the collection is numerous enough to allow comparison of multiple objects from the same or similar moulds. Other groups have cut or lustre-painted decoration. Four complete objects are decorated by a rare scratched-glass technique and have enabled a new study of the technique.[56]

Coins

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The collection's 15,000 gold, silver, and copper coins come from the entire Islamic world and span the time period from 700 to 2000 AD. For many series of coin, the Khalili collection is more numerous and diverse than any other.[58] The coins include a dozen from the first issue of North African Arab-Latin gold coins, from 704 and 705 AD, as well as early gold dinars.[58] Later holdings include a unique gold dinar from the reign of the Ilkhanid Emperor Musa Khan and others, with signs of the zodiac, from the reign of Mughal Emperor Jahangir.[59] A gold dinar from 697 AD is an example of the earliest known issue with only Arabic inscriptions.[60]

Scientific instruments

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Throughout the history of Islam, its rituals have made use of scientific procedures to find the direction of Mecca and to determine the times of prayers within the lunar calendar.[61] Around two hundred objects in the collection relate to medieval Islamic science and medicine, including astronomical instruments, tools, scales, weights, and supposedly magical items intended for medical use.[62] The astrolabes include an exceptionally large example commissioned by Shah Jahan[63][64] and a rare example with Hebrew inscriptions, dating from around 1300.[65] The collection has one of the largest groups of Islamic globes, of diverse types and dates. One that was made in 1285–6 is among the oldest known examples. There are also quadrants of wood and of metal.[65] Magical healing bowls, inscribed with verses from the Quran and other writing, were common in the Islamic world from the 12th century onwards. The collection has a 12th-century example from Syria.[66] Made for the ruler Nur al-Din Mahmud Zengi, it has an inscription promising to cure anyone who drinks from it of any poison or affliction.[67]

Architectural elements

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The collection's architectural elements and tombstones bear dates from the 13th century to the 19th. They include ceramic tiles from Ilkhanid Iran, 15th-century Spain, and 18th–19th century Multan.[68] The tombstones are of varying origins and materials, including a carved and calligraphed stele, nearly Vorlage:Convert high, from Northern India.[68] A Tunisian marble tombstone from 1044, with Kufic inscriptions, stands at over a metre high.[68] A carved wooden cenotaph, dated 1496–7 AD, from a shrine in the Caspian area of Iran bears the craftsman's signature and the names of donors.[68] Royal palaces were sometimes decorated with stone sculpture; the collection has heads from two examples; an 8th- or 9th-century limestone head shows the influence of Buddhist depictions of Bodhisattvas.Vorlage:Sfn The collection also includes jali (carved sandstone window grilles) and a group of marble carvings from Ghazni in modern-day Afghanistan.[68]

Gallery

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]-

Lustreware dish decorated with Kufic script, probably Egypt, 8th or 9th century

-

Crowned head, Central Asia, 8th or 9th century

-

Casket with the remains of a combination Lock, Jazira, early 13th century

-

Iron and steel war mask, Anatolia or Western Iran, late 15th century

-

Carpet with star medallions, Uşak, Turkey, late 15th or early 16th century

-

Dagger and sheath with a steel blade damascened with gold, Ottoman Turkey, 1540–50

-

Seal of Tahmasp I cut into a flawless rock crystal, 1555–6

Activities

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Exhibitions

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]This collection was the basis in 2008 for the first comprehensive exhibition of Islamic art to be staged in the Middle East, at the Emirates Palace in Abu Dhabi. This was also the largest exhibition of Islamic art held anywhere up to that date.[6][69] Exhibitions drawing exclusively from the collection have been held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris and the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam as well as at many other museums and institutions worldwide.[8] An academic study of the Arts of Islam exhibition held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2007 found that Khalili covered transport and insurance costs as well as providing the objects free of charge. He also had curatorial input into the exhibition.[70] The bulk of the exhibition was of secular art works and the presentation focused on their artistic value rather than religious messages. The exhibitions emphasise links between the Abrahamic religions, highlighting art works made by Jews and Muslims working together, as well as works that depict figures from all three religions.[70]

Empire of the Sultans: Ottoman Art from the Khalili Collection

- July–Sep 1995 Musee Rath, Geneva, Switzerland

- July–Oct 1996 Brunei Gallery, School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK

- Dec 1996 – June 1997 Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel

- Feb–Apr 2000 Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, Florida, USA

Marvels of the East: Indian Paintings of the Mughal Period from the Khalili Collection

- May–July 2000, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Israel

Empire of the Sultans: Ottoman Art from the Khalili Collection

- July–Oct 2000 Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan, USA

- Oct 2000 – Jan 2001 Albuquerque Museum of Art and History, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA

- Jan–Apr 2001 Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon, USA

- Aug–Oct 2001 Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA

- Oct 2001 – Jan 2002 Bruce Museum of Arts and Science, Greenwich, Connecticut, USA

- Feb–Apr 2002 Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

- May–July 2002 North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, North Carolina, USA

- Aug 2002 – Jan 2003 Museum of Art, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA

Ornements de la Perse: Islamic Patterns in 19th Century Europe

- Oct–Dec 2002 Leighton House Museum, London, UK

Empire of the Sultans: Ottoman Art from the Khalili Collection

- Feb–Apr 2003 Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, USA

- May–Aug 2003 Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, Tennessee, USA

- Aug–Nov 2003 Museum of Arts and Sciences, Macon, Georgia, USA

- Nov 2003 – Feb 2004 Frick Art and Historical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

The Arts of Islam: Treasures from the Nasser D. Khalili Collection

- June–Sep 2007 Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia[71]

- Jan–May 2008 Gallery One, Emirates Palace, Abu Dhabi, UAE[72][25][73]

- Oct 2009 – Mar 2010 Institut du monde arabe, Paris, France

Passion for Perfection: Islamic Art from the Khalili Collection

- Dec 2010 – Apr 2011 Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Loans to museums and galleries

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Earthly Beauty, Heavenly Art: The Art of Islam, an exhibition of objects from the Islamic collection and the State Hermitage Museum was seen at:[8]

- Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam, Dec 1999 – Apr 2000

- State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, 2000 – Sep 2001

- Hermitage Rooms, Somerset House, London (as Heaven on Earth: Art From Islamic Lands – Selected objects from the Khalili Collection and The State Hermitage Museum), March–August 2004

Publications

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Khalili employs a production staff and has commissioned more than 30 academic experts to document the collection in a 30-volume series of books, whose publication he has subsidised.[4][74] Each volume includes scholarly research on the collection's objects, as well as essays about Islamic art for a general audience.[4] The General Editor is Julian Raby, formerly a lecturer at the University of Oxford and Director at the Freer Gallery of Art. Other contributors include Sheila Blair, Professor of Islamic and Asian Art at the Boston College; François Déroche of the Collège de France; Geoffrey Khan of the University of Cambridge; and J. M. Rogers of SOAS, University of London.[75] Khalili, who has a PhD in Islamic lacquers from SOAS,[3] is a co-author of the volume on the collection's lacquers.[76] A review said that each volume "has been produced to a standard that is seldom seen in this small corner of the art world [...] backed up by solid scholarship from respected authorities".[77] Reviewing the first group of volumes, Robert Irwin described the production as "of a very high standard indeed. The catalogues are in their own way works of art."[22]

- François Déroche: Volume I – The Abbasid Tradition: Qur'ans of the 8th to the 10th centuries AD. The Nour Foundation, 1992, ISBN 978-1-874780-51-9.

- David James: Volume II – The Master Scribes: Qur'ans of the 10th to 14th centuries AD. The Nour Foundation, 1992, ISBN 978-1-874780-52-6.

- David James: Volume III – After Timur: Qur'ans of the 15th and 16th centuries. The Nour Foundation, 1992, ISBN 978-0-19-727602-0.

- Manijeh Bayani, Anna Contadini, Tim Stanley: Volume IV, Part I – The Decorated Word: Qur'ans of the 17th to 19th centuries. The Nour Foundation, 1999, ISBN 978-0-19-727603-7.

- Manijeh Bayani, Anna Contadini, Tim Stanley: Volume IV, Part II – The Decorated Word: Qur'ans of the 17th to 19th centuries. The Nour Foundation, 2009, ISBN 978-1-874780-54-0.

- Nabil F. Safwat: Volume V – The Art of the Pen: Calligraphy of the 14th to 20th Centuries. The Nour Foundation, 1996, ISBN 978-0-19-727604-4.

- Geoffrey Khan: Volume VI – Bills, Letters and Deeds: Arabic Papyri of the 7th to 11th Centuries. The Nour Foundation, 1993, ISBN 978-1-874780-56-4.

- Deborah Freeman: Volume VII – Learning, Piety and Poetry. Manuscripts from the Islamic world. The Nour Foundation, 1993, ISBN 978-1-874780-84-7.

- Linda York Leach: Volume VIII – Paintings from India. The Nour Foundation, 1998, ISBN 978-0-19-727624-2.

- Ernst J. Grube: Volume IX – Cobalt and Lustre: The first centuries of Islamic pottery. The Nour Foundation, 1994, ISBN 978-0-19-727607-5.

- Ernst J. Grube: Volume X – A Rival to China. Later Islamic pottery. The Nour Foundation, 2007, ISBN 978-1-874780-87-8.

- Michael Spink: Volume XI – Brasses, Bronze & Silver of the Islamic Lands, Part I and II. The Nour Foundation, 2009, ISBN 978-1-874780-88-5.

- Francis Maddison: Volume XII – Science, Tools & Magic: Body and Spirit, Mapping the Universe, Part I and Mundane Bodies, Part II. The Nour Foundation, 1997, ISBN 978-0-19-727610-5.

- Manijeh Bayani: Volume XIII – Seals and Talismans. The Nour Foundation, 1997, ISBN 978-1-874780-77-9.

- Steven Cohen: Volume XIV – Textiles, Carpets and Costumes, Part I and II. The Nour Foundation, 2011, ISBN 978-1-874780-78-6.

- Sidney M. Goldstein: Volume XV – Glass: From Sasanian antecedents to European imitations. The Nour Foundation, 2005, ISBN 978-1-874780-50-2.

- Marian Wenzel: Volume XVI – Ornament and Amulet: Rings of the Islamic Lands. The Nour Foundation, 1992, ISBN 978-0-19-727614-3.

- Michael Spink, Jack Ogden: Volume XVII – The Art of Adornment: Jewellery of the Islamic lands. The Nour Foundation, 2013, ISBN 978-1-874780-86-1.

- Pedro Moura Carvalho: Volume XVIII – Gems and Jewels of Mughal India. Jewelled and enamelled objects from the 16th to 20th centuries. The Nour Foundation, 2010, ISBN 978-1-874780-72-4.

- Aram R. Vardanyan: Volume XIX – Dinars and Dirhams. Coins of the Islamic lands. The early period, Part I. The Nour Foundation, 2006, ISBN 978-1-874780-82-3.

- Aram R. Vardanyan: Volume XX – Dinars and Dirhams. Coins of the Islamic lands. The later period, Part II. The Nour Foundation, 2006, ISBN 978-1-874780-83-0.

- David Alexander: Volume XXI – The Arts of War: Arms and Armour of the 7th to 19th centuries. The Nour Foundation, 1992, ISBN 978-1-874780-61-8.

- Nasser D. Khalili, B. W. Robinson, Tim Stanley: Volume XXII – Lacquer of the Islamic Lands, Part I. The Nour Foundation, 1996, ISBN 978-1-874780-62-5.

- Nasser D. Khalili, B. W. Robinson, Tim Stanley: Volume XXII – Lacquer of the Islamic Lands, Part II. The Nour Foundation, 1997, ISBN 978-1-874780-63-2.

- Stephen Vernoit: Volume XXIII – Occidentalism. Islamic Art in the 19th Century. The Nour Foundation, 1997, ISBN 978-0-19-727620-4.

- Ralph Pinder-Wilson, Mehreen Chida-Razvi: Volume XXIV – Monuments and Memorials. Carvings and tile work from the Islamic world. The Nour Foundation, 2006, ISBN 978-1-874780-85-4.

- Eleanor Sims, Manijeh Bayani, Tim Stanley: Volume XXV, Part I – The Tale and the Image. Illustrated manuscripts and album paintings from Iran and Turkey (Part One). The Nour Foundation, 2006, ISBN 978-1-874780-80-9.

- J. M. Rogers, Manijeh Bayani: Volume XXV, Part II – The Tale and the Image. Illustrated manuscripts and album paintings from Iran and Turkey (Part Two). The Nour Foundation, 2006, ISBN 978-1-874780-81-6.

- Shelia Blair: Volume XXVII – A Compendium of Chronicles: Rashid al-Din's illustrated history of the world. The Nour Foundation, 1995, ISBN 978-1-874780-65-6.

The monographs in the Studies in the Khalili Collection series present research about objects in the Islamic Art collection:

- Geoffrey Khan: Volume I – Selected Arabic Papyri. The Nour Foundation, 1992, ISBN 978-1-874780-66-3.

- Svat Soucek: Volume II – Piri Reis and Turkish Mapmaking after Columbus, The Khalili Portolan Atlas. The Nour Foundation, 1996, ISBN 978-1-874780-67-0.

- Nicholas Sims-Williams: Volume III – (Part One) Bactrian Documents from Northern Afghanistan, Legal and Economic Documents. The Nour Foundation, 2012, ISBN 978-1-874780-92-2.

- Nicholas Sims-Williams: Volume III – (Part Two) Bactrian Documents from Northern Afghanistan, Letters and Buddhist Texts. The Nour Foundation, 2007, ISBN 978-1-874780-90-8.

- Nicholas Sims-Williams: Volume III – (Part Three) Bactrian Documents from Northern Afghanistan, Plates. The Nour Foundation, 2012, ISBN 978-1-874780-91-5.

- Tony Goodwin: Volume IV – Arab-Byzantine Coinage. The Nour Foundation, 2005, ISBN 978-1-874780-75-5.

- Geoffrey Khan: Volume V – Arabic Documents from Early Islamic Khurasan. The Nour Foundation, 2007, ISBN 978-1-874780-71-7.

- Nada Chaldecott: Volume VI – Turcoman Jewellery. The Nour Foundation, 2020, ISBN 978-1-874780-93-9.

Digitisation

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]For the 2023 video game Assassin's Creed Mirage, the Khalili Collections were one of four partner institutions providing images for the game's educational database. An astrolabe and a statuette of a camel and rider from the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art were among the objects used to illustrate the game's setting of 9th century Baghdad.[78][79] Images from the collection are also being shared on Wikipedia and related platforms[80] as well as on Google Arts & Culture.[81]

Reception

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]The Wall Street Journal has said that Khalili's is the greatest collection of Islamic Art in existence.[82] According to Edward Gibbs, Chairman of Middle East and India at Sotheby's, it is the best such collection in private hands.[83] Historian of astronomy David A. King has written that "Many of the objects [...] are works of considerable and occasionally exceptional beauty, be they illuminated manuscripts or scientific works of art."[84] Tahir Shah, writing in Saudi Aramco World, described Khalili's collection as the most extensive such collection in the world, as well as the best-catalogued: "Its embrace of virtually every known area of craftsmanship ever pursued in Islamic lands is unprecedented."[4]

See also

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]References

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Sources

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- Vorlage:Free-content attribution

- Nasser D. Khalili: The timeline history of Islamic art and architecture. Worth, London 2005, ISBN 1-903025-17-6.

- J. M. Rogers: The arts of Islam : treasures from the Nasser D. Khalili collection. Revised and expanded Auflage. Tourism Development & Investment Company (TDIC), Abu Dhabi 2008, OCLC 455121277.

Further reading

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- David Khalili: The Art of Peace: Eight collections, one vision. Penguin Random House, London 2023, ISBN 978-1-5299-1818-2, S. 76–83, 149–183.

External links

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]{{Nasser Khalili}} {{Islamic art}} {{authority control}} [[Category:Islamic art]] [[Category:Khalili Collections|Islamic Art]]

- ↑ a b The Khalili Collections major contributor to "Longing for Mecca" exhibition at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam. UNESCO, 16. April 2019, archiviert vom am 7. April 2022; abgerufen am 25. Juni 2020.

- ↑ a b Andrew McKie: The British Museum's Pilgrimage In: The Wall Street Journal, 27 January 2012. Abgerufen im 10 September 2019

- ↑ a b c d William Green: Iranian Student With $750 Turns Billionaire Made by Islamic Art In: Bloomberg, 30 March 2010. Abgerufen im 10 September 2019

- ↑ a b c d e Tahir Shah: The Khalili Collection of Islamic Art. In: Saudi Aramco World. 45. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, 1994 (aramcoworld.com).

- ↑ Martin Gayford: Healing the world with art In: The Independent, 16 April 2004. Abgerufen im 10 September 2019

- ↑ a b c Susan Moore: A leap of faith In: Financial Times, 12 May 2012. Abgerufen im 10 September 2019

- ↑ BBC World Service – Arts & Culture – Khalili Collection: Picture gallery. BBC, 14. Dezember 2010, abgerufen am 30. September 2019.

- ↑ a b c The Eight Collections. In: nasserdkhalili.com. Archiviert vom am 28. Oktober 2022; abgerufen am 10. September 2019.

- ↑ The Khalili Family Trust | Collections Online | British Museum. British Museum, abgerufen am 5. Juni 2020.

- ↑ Silke Ackermann: [Review] The Near and Middle East – Francis Maddison, Emilie Savage-smith: Science, tools and magic. In: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 62. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, Juni 1999, ISSN 1474-0699, S. 339–340, doi:10.1017/S0041977X00016840 (cambridge.org).

- ↑ Pedro Moura Carvalho: Enamels of the world, 1700–2000 : the Khalili collections. Hrsg.: Haydn Williams. Khalili Family Trust, 2009, ISBN 978-1-874780-17-5, Enamel in the Islamic Lands, S. 186–215.

- ↑ Nasser D. Khalili: The art and tradition of the Zuloagas: Spanish damascene from the Khalili Collection. Hrsg.: James D. Lavin. Khalili Family Trust in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, Oxford 1997, ISBN 1-874780-10-2, Foreword.

- ↑ £2m gift for Middle Eastern art. In: BBC News. 9. Juli 2004.

- ↑ Michael Binyon: Islamic studies gain £2 1/4 m In: The Times, 8 July 2004. Abgerufen im 24 September 2020

- ↑ Irina Bokova: Address by Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO on the occasion of the ceremony to designate Professor Nasser David Khalili as a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador. UNESCO, 16. Oktober 2012, abgerufen am 7. August 2020.

- ↑ The Timeline History of Islamic Art and Architecture. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 23. September 2020.

- ↑ Lucian Harris: Paradise on earth. In: Museums Association. 13. November 2009, abgerufen am 18. Februar 2021.

- ↑ a b The Abbasid Tradition: Qur'ans of the 8th to the 10th centuries AD. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 11. Februar 2021.

- ↑ The Master Scribes: Qur'ans of the 10th to 14th centuries AD. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 11. Februar 2021.

- ↑ After Timur: Qur'ans of the 15th and 16th centuries. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 11. Februar 2021.

- ↑ The Decorated Word: Qur'ans of the 17th to 19th centuries. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 11. Februar 2021.

- ↑ a b Robert Irwin: Review: Calligraphic Significances: Catalogues of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art. In: British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 25. Jahrgang, Nr. 2. Taylor & Francis, November 1998, ISSN 1353-0194, S. 355–361, JSTOR:40662688.

- ↑ , Deroche, Francois.: The Abbasid Tradition Qur'ans of the 8th And 10th Centuries Ad. I B Tauris & Co Ltd, 2005, ISBN 978-1-874780-51-9.

- ↑ Keith E. Small: [[Textual Criticism and Qur'an Manuscripts]]. Lexington Books, 2011, ISBN 978-0-7391-4291-2, S. 21.

- ↑ a b Lucien de Guise: Bridging the Gulf. In: Asian Art. April 2008, S. 15–16.

- ↑ History and epic paintings from Iran and Turkey (Part One). In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 17. September 2019.

- ↑ Ten folios from the Shahnamah of Firdawsi made for Shah Tahmasp I. In: Discover Islamic Art. 2021, abgerufen am 10. Mai 2021.

- ↑ Susannah Woolmer: Around the galleries. In: Apollo. 162. Jahrgang, Nr. 524, Oktober 2005, S. 83.

- ↑ a b c d The Tale and the Image Part Two: Illustrated manuscripts and album paintings from Iran, Turkey and Egypt. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 2. Februar 2021.

- ↑ History and epic paintings from Iran and Turkey (Part One). In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 2. Februar 2021.

- ↑ Louise Ryan: Transcending boundaries: The arts of Islam: Treasures from the Nassar D. Khalili collection (Thesis). University of Western Sydney, 2015, Vorlage:ProQuest, S. 82–87.

- ↑ a b Catherine Asher: Catherine B. Asher. Review of "The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, vol. 8" by Linda York Leach. In: Caa.reviews. 15. Februar 2002, ISSN 1543-950X, doi:10.3202/caa.reviews.2002.3 (caareviews.org).

- ↑ a b The Art of the Pen: Calligraphy of the 14th to 20th Centuries. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 9. Februar 2021.

- ↑ a b c David J. Roxburgh: Review of The Art of the Pen: Calligraphy of the 14th to 20th Centuries. In: Ars Orientalis. 28. Jahrgang, 1998, ISSN 0571-1371, S. 118–120, JSTOR:4629537 (jstor.org).

- ↑ Metin Sözen, İlhan Akşit: The evolution of Turkish art and architecture. Haşet Kitabevi, 1987.

- ↑ Album of calligraphic specimens. In: Explore Islamic Art Collections. 2021, abgerufen am 15. März 2021.

- ↑ a b c Brasses, Bronze & Silver of the Islamic Lands. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 17. September 2019.

- ↑ a b c d The Art of Adornment: Jewellery of the Islamic lands. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 9. Februar 2021.

- ↑ a b c J. W. Allan: The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art; Arabic papyri and selected material from the Khalili Collection, Studies in the Khalili Collection I. In: Journal of the History of Collections. 10. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, 1. Januar 1998, ISSN 0954-6650, S. 226–227, doi:10.1093/jhc/10.2.226 (oup.com).

- ↑ a b Gems and Jewels of Mughal India. Jewelled and enamelled objects from the 16th to 20th centuries. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 9. Februar 2021.

- ↑ Water vessel and tobacco bowl support from a huqqa. In: Discover Islamic Art. 2021, abgerufen am 2. Februar 2021.

- ↑ Order of the lion and the Sun, presented to Sir John Kinneir MacDonald, the East India Company's envoy to Iran (1824–30). In: Discover Islamic Art. 2021, abgerufen am 2. Februar 2021.

- ↑ Ornament and Amulet: Rings of the Islamic Lands. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 1. Februar 2021.

- ↑ Gems and Jewels of Mughal India. Jewelled and enamelled objects from the 16th to 20th centuries. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 17. September 2019.

- ↑ a b The Arts of War: Arms and Armour of the 7th to 19th centuries. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 17. September 2019.

- ↑ J. W. Allan: The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art. In: Journal of the History of Collections. 6. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 1. Januar 1994, ISSN 0954-6650, S. 117–119, doi:10.1093/jhc/6.1.117 (oup.com).

- ↑ a b Seals and Talismans part one. In: Khalili Collections. Archiviert vom am 1. Februar 2021; abgerufen am 28. Januar 2021.

- ↑ Seals and Talismans part two. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 28. Januar 2021.

- ↑ Seal of the Ottoman Sultan 'Abd al-'Aziz. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 15. März 2021.

- ↑ a b c Textiles, Carpets and Costumes. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 17. September 2019.

- ↑ a b Lacquer of the Islamic Lands (Part One and Part Two). In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 17. September 2019.

- ↑ Phil Baker: Khalili's collection. In: The Art Book. 2. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, Dezember 1995, ISSN 1368-6267, S. 8, doi:10.1111/j.1467-8357.1995.tb00290.x.

- ↑ a b Priscilla P. Soucek: Review of Cobalt and Lustre: The First Centuries of Islamic Pottery, vol. 9, The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art: Ceramics of the Islamic World in the Tareq Rajab Museum, Géza Fehérvári. In: Studies in the Decorative Arts. 12. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 2004, ISSN 1069-8825, S. 155–158, doi:10.1086/studdecoarts.12.1.40663108, JSTOR:40663108 (jstor.org).

- ↑ Brooke Olson Vuckovic: Heavenly Journeys, Earthly Concerns. Routledge, 2004, ISBN 978-1-135-88524-3, S. 48 (google.com [abgerufen am 25. Oktober 2015]).

- ↑ A Rival to China. Later Islamic pottery. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 28. Januar 2021.

- ↑ a b Glass: From Sasanian antecedents to European imitations. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 29. Januar 2021.

- ↑ Melanie Gibson: Glass : from Sasanian antecedents to European imitations. Nour Foundation, London 2005, ISBN 1-874780-50-1, 'Admirably Ornamented Glass', S. 262, 270.

- ↑ a b Dinars and Dirhams. Coins of the Islamic lands. The early period (Part One). In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 17. September 2019.

- ↑ Dinars and Dirhams. Coins of the Islamic lands. The later period (Part Two). In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 28. Januar 2021.

- ↑ Gold Dinar (Umayyad Post-Reform Type). In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 15. März 2021.

- ↑ Vorlage:Citation

- ↑ Science, Tools & Magic: (Part Two) Mundane Worlds. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 28. Januar 2021.

- ↑ Nahla Nassar: A monumental planispheric astrolabe made for Shah Jahan, most probably by Diya' al-Din Muhammad Lahori. In: Discover Islamic Art. 2021, abgerufen am 1. Februar 2021.

- ↑ Sreeramula Rajeswara Sarma: Astrolabes in Medieval Cultures. BRILL, 2019, ISBN 978-90-04-38786-7, A Monumental Astrolabe Made for Shāh Jahān and Later Reworked with Sanskrit Legends, S. 198–262 (google.com).

- ↑ a b Owen Gingerich: Book Review: Art in Islamic Scientific Instruments: Science, Tools and Magic: The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, xii. In: Journal for the History of Astronomy. 30. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, August 1999, ISSN 0021-8286, S. 336–337, doi:10.1177/002182869903000324 (sagepub.com).

- ↑ Venetia Porter, Liana Saif, Emilie Savage-Smith: A companion to Islamic art and architecture. Hrsg.: Finbarr Barry Flood, Gülru Necipoğlu. Wiley, 2017, ISBN 978-1-119-06857-0, Medieval Islamic Amulets, Talismans, and Magic.

- ↑ Charles Burnett: [Review] Science, tools and magic. In: Medical History. 43. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, Oktober 1999, ISSN 0025-7273, S. 530–531, doi:10.1017/S0025727300065893, PMC 1044200 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ a b c d e Monuments and Memorials. Carvings and tile work from the Islamic world. In: Khalili Collections. Abgerufen am 17. September 2019.

- ↑ Khalili makes dazzling debut. In: Arabic Knight. 10. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, S. 58–64.

- ↑ a b Louise Frances Ryan: Australian museums in the 'age of risk': a case study. In: Museum Management and Curatorship. 32. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, 8. August 2017, ISSN 0964-7775, S. 372–394, doi:10.1080/09647775.2017.1345647 (tandfonline.com).

- ↑ Collector shares beauty of Islamic art with world. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 25. Juni 2007, abgerufen am 24. September 2020.

- ↑ Sarah H. Bayliss: 'A Positive Understanding of Islam'. In: ARTnews. 1. Mai 2008, abgerufen am 18. Februar 2021.

- ↑ Tim Stanley: Review of The Arts of Islam. Treasures From the Nasser D. Khalili Collection. In: The Burlington Magazine. 151. Jahrgang, Nr. 1271, 2009, ISSN 0007-6287, S. 112, JSTOR:40480075 (jstor.org).

- ↑ Susan Moore: An Islamic symphony: David Khalili talks about his collection. In: Apollo. 167. Jahrgang, Nr. 552, März 2008, S. 48.

- ↑ Referenzfehler: Ungültiges

<ref>-Tag; kein Text angegeben für Einzelnachweis mit dem Namen official. - ↑ Lacquer of the Islamic Lands. OCLC 906736903 (worldcat.org [abgerufen am 21. Januar 2021]).

- ↑ Lucien de Guise: [Review:] The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art: Volume XVIII Gems and Jewels of Mughal India. In: Apollo. 173. Jahrgang, Nr. 585, März 2011.

- ↑ Inga Mainka: Assassin's Creed Mirage Goes Back To Its Roots: Most Accurate AC In Years. In: EarlyGame. 6. Juli 2023, abgerufen am 20. Juli 2023 (englisch).

- ↑ 'My son showed me Assassin's Creed, now I've helped build the new one'. In: STV News. 5. Juli 2023, abgerufen am 20. Juli 2023 (britisches Englisch).

- ↑ Jo Lawson-Tancred: Around the world in 35,000 objects – and a handful of clicks In: Apollo, 11 October 2019. Abgerufen im 5 May 2021

- ↑ The Khalili Collections. In: Google Arts & Culture. Abgerufen am 20. Juli 2023 (englisch).

- ↑ Andrew McKie: The British Museum's Pilgrimage In: Wall Street Journal, 27 January 2012. Abgerufen im 10 September 2019 (amerikanisches Englisch).

- ↑ William Green: Iranian Student With $750 Turns Billionaire Made by Islamic Art In: Bloomberg, 30 March 2010. Abgerufen im 10 September 2019

- ↑ David A. King: Cataloguing Medieval Islamic Astronomical Instruments. In: Bibliotheca Orientalis. 57. Jahrgang, Nr. 3/4, S. 247–258, doi:10.2143/BIOR.57.3.2015769 (peeters-leuven.be).