Benutzer:Colonestarrice/Königreich Frankreich

| Royaume de France Königreich Frankreich 987–1791, 1814–1815 und 1815–1848 | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Wahlspruch: Montjoye Saint Denis | |||||

| Amtssprache | Französisch (offiziell ab 1539) | ||||

| Hauptstadt | Paris (987–1682, 1789–1792 und 1814-1848), Versailles (1682–1789) | ||||

| Staatsform – 987 bis 1648 – 1648 bis 1791 – 1814 bis 1848 |

Monarchie Feudal Monarchie Absolute Monarchie Konstitutionelle Monarchie | ||||

| Staatsoberhaupt – 987 bis 996 – 1180 bis 1223 – 1422 bis 1461 – 1589 bis 1610 – 1643 bis 1715 – 1774 bis 1791 – 1814 bis 1824 – 1824 bis 1830 – 1830 bis 1848 |

König Hugo Capet Philip II Karl VII. Heinrich IV. Ludwig XIV. Ludwig XVI. Ludwig XVIII. Karl X. Louis-Philippe I. | ||||

| Regierungschef – 1815 – 1847 bis 1848 |

Premierminister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand François Guizot | ||||

| Währung | Livre | ||||

| Nationalhymne | Marche Henri IV (1590–1830) | ||||

| Gründung | 843: Staatsgründung 1814: Erste Restauration 1815: Zweite Restauration | ||||

| Auflösung | 843: Französische Revolution 1815: Rückkehr Napoleons 1830: Julirevolution | ||||

| Karte | |||||

| |||||

Das Königreich Frankreich (französisch: Royaume de France) bzw. Königreich der Franzosen war ein Königreich in der Zeit des Mittelalters und der Frühen Neuzeit. Es war einer der mächtigsten Reiche Europas und eine Großmacht im Spätmittelalter und dem Hundertjährigen Krieg. Ebenfalls war es ein frühes Kolonialreich, mit besetzten Territorien und Überseegebieten auf der ganzen Welt.

Das Königreich ging aus dem Westfränkischen Reich hervor, dass durch den Vertrag von Verdun später den westlichen Teil des Fränkischen Reichs darstellte. Bis 987 herrschten die Karolinger über dieses Gebiet, nach dieser Zeit wurde wurde Hugo Capet zum König der Franken gewählt, der wiederum die Kapetinger Dynastie ins Leben ruf. Das Reich behielt den Namen Königreich der Franken und sein Herrscher den Titel rex Francorum (König der Franken) bis ins Spätmittelalter. Ab 1190 lies sich Philip II Roi de France (König der Franzosen) nennen, er war damit der erste König der diesen Titel trug. Das Königreich wurde von den Kapetinger, den Valois und den Bourbons bis zur französischen Revolution 1792 beherrscht.

Während des Mittelalters war das Reich eine dezentralisierte feudal Monarchie. In England und Katalonien (heute ein Teil von Spanien) war die Autorität des französischen Königs kaum zu spüren. Lothringen und Burgund waren damals Lehen des Heiligen Römischen Reichs und noch kein Teil des Königreich Frankreichs. Während des Spätmittelalters legte der König von England Anspruch auf den französischen Thron, welches zu einer Reihe von Konflikten führte, die Heute als der Hundertjährige Krieg (1337–1453) bekannt sind. Abschließend versuchte das Königreich seinen Einfluss in Italien zu verbreiten wurde in folge jedoch in den italienischen Kriegen (1494–1559) vom spanischen Königreich zurückgeschlagen.

In der Neuzeit wurde das Königreich zunehmend zentraler; die französische Sprache begann andere Sprachen zu verdrängen, der Monarch expandierte seine absolute Macht innerhalb des Reiches. Im Religiösen spaltete sich das Königreich in eine katholische Mehrheit und eine evangelische Minderheit. Frankreich beanspruchte große Teile Nordamerikas welches zu mehreren Kriegen mit Großbritannien führte. 1763 verlor das Königreich durch diese viele seiner besetzten Territorien. Frankreichs Intervention in der amerikanischen Revolution sicherte die Unabhängigkeit der Vereinigten Staaten vom Britischen Empire.

Im Jahr 1791 akzeptierte der König Frankreichs eine Verfassung, ein Jahr später wurde das Königreich dennoch gestürzt und mit der Ersten Französischen Republik ersetzt. 1814 wurde die Monarchie wiederhergestellt und blieb bis zur Julirevolution von 1830 bestehen.

Geschichte[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Westfrankenreich[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

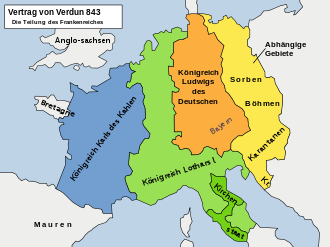

Während der Herrschaft von Karl dem Großen eroberten die Wikinger nördliche und westliche Areale des Fränkischen Reichs. Nach dem Tod von Karl 814 war es seinen Erben nicht möglich die Einigkeit im Reich zu erhalten und es fing an zu zerfallen. Mit dem Vertrag von Verdun 843 wurde das Reich in drei Teile aufgeteilt. Die Herrschaft Karl II. über das Westfränkische Reich stellte später die Basis für das Königreich der Franken dar. Nach dem Tod von Lothar II. 869 wurde Karl II. auch zum König von Lotharii Regnum gekrönt, er wurde im Vertrag von Meerssen (870) jedoch dazu gezwungen große Teile des Mittelreichs an seine Brüder abzugeben.

Den Wikingern war es in dieser Zeit möglich mit ihren Langschiffen durch die Loire und die Seine noch weiter ins Inland einzudringen, wo sie Unheil und Terror verbreiteten. Während der Herrschaft von Karl III. war es den Normannen unter Rollo von Norwegen möglich die Seine stromabwärts von Paris zu besetzen, wodurch später die Normandie entstand.

Hochmittelalter[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Im Jahr 987 erlangte Hugo Capet, Herzog von Frankreich und Graf von Paris, den Thron und etablierte daraufhin die Kapetinger Dynastie. Mit ihren zwei Nebenlinien dem Haus Valois und dem Haus Bourbon herrschten die Kapetinger 800 Jahre lang über das Königreich.

The old order left the new dynasty in immediate control of little beyond the middle Seine and adjacent territories, while powerful territorial lords such as the 10th- and 11th-century counts of Blois accumulated large domains of their own through marriage and through private arrangements with lesser nobles for protection and support.

The area around the lower Seine became a source of particular concern when Duke William took possession of the kingdom of England by the Norman Conquest of 1066, making himself and his heirs the King's equal outside France (where he was still nominally subject to the Crown).

Henry II inherited the Duchy of Normandy and the County of Anjou, and married France's newly divorced ex-queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who ruled much of southwest France, in 1152. After defeating a revolt led by Eleanor and three of their four sons, Henry had Eleanor imprisoned, made the Duke of Brittany his vassal, and in effect ruled the western half of France as a greater power than the French throne. However, disputes among Henry's descendants over the division of his French territories, coupled with John of England's lengthy quarrel with Philip II, allowed Philip II to recover influence over most of this territory. After the French victory at the Battle of Bouvines in 1214, the English monarchs maintained power only in southwestern Duchy of Guyenne.[5]

Spätmittelalter und der Hunderjährige Krieg[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The death of Charles IV of France in 1328 without male heirs ended the main Capetian line. Under Salic law the crown could not pass through a woman (Philip IV's daughter was Isabella, whose son was Edward III of England), so the throne passed to Philip VI, son of Charles of Valois. This, in addition to a long-standing dispute over the rights to Gascony in the south of France, and the relationship between England and the Flemish cloth towns, led to the Hundred Years' War of 1337–1453. The following century was to see devastating warfare, peasant revolts (the English peasants' revolt of 1381 and the Jacquerie of 1358 in France) and the growth of nationalism in both countries.[6]

The losses of the century of war were enormous, particularly owing to the plague (the Black Death, usually considered an outbreak of bubonic plague), which arrived from Italy in 1348, spreading rapidly up the Rhone valley and thence across most of the country: it is estimated that a population of some 18–20 million in modern-day France at the time of the 1328 hearth tax returns had been reduced 150 years later by 50 percent or more.[7]

Renaissance und Reformation[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The Renaissance era was noted for the emergence of powerful centralized institutions, as well as a flourishing culture ( much of it imported from Italy).[8] The kings built a strong fiscal system, which heightened the power of the king to raise armies that overawed the local nobility.[9] In Paris especially there emerged strong traditions in literature, art and music. The prevailing style was classical.[10][11]

The Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts was signed into law by Francis I in 1539. Largely the work of Chancellor Guillaume Poyet, it dealt with a number of government, judicial and ecclesiastical matters. Articles 110 and 111, the most famous, called for the use of the French language in all legal acts, notarised contracts and official legislation.

Italienische Kriege[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

After the Hundred Years' War, Charles VIII of France signed three additional treaties with Henry VII of England, Maximilian I of Habsburg, and Ferdinand II of Aragon respectively at Étaples (1492), Senlis (1493) and in Barcelona (1493). These three treaties cleared the way for France to undertake the long Italian Wars (1494–1559), which marked the beginning of early modern France. French efforts to gain dominance resulted only in the increased power of the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperors of Spain.

Religionskriege[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Barely were the Italian Wars over, when France was plunged into a domestic crisis with far-reaching consequences. Despite the conclusion of a Concordat between France and the Papacy (1516), granting the crown unrivalled power in senior ecclesiastical appointments, France was deeply affected by the Protestant Reformation's attempt to break the hegemony of Catholic Europe. A growing urban-based Protestant minority (later dubbed Huguenots) faced ever harsher repression under the rule of Francis I's son King Henry II. After Henry II's death in a joust, the country was ruled by his widow Catherine de' Medici and her sons Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. Renewed Catholic reaction headed by the powerful dukes of Guise culminated in a massacre of Huguenots (1562), starting the first of the French Wars of Religion, during which English, German, and Spanish forces intervened on the side of rival Protestant and Catholic forces. Opposed to absolute monarchy, the Huguenot Monarchomachs theorized during this time the right of rebellion and the legitimacy of tyrannicide.[12]

The Wars of Religion culminated in the War of the Three Henrys in which Henry III assassinated Henry de Guise, leader of the Spanish-backed Catholic league, and the king was murdered in return. After the assassination of both Henry of Guise (1588) and Henry III (1589), the conflict was ended by the accession of the Protestant king of Navarre as Henry IV (first king of the Bourbon dynasty) and his subsequent abandonment of Protestantism (Expedient of 1592) effective in 1593, his acceptance by most of the Catholic establishment (1594) and by the Pope (1595), and his issue of the toleration decree known as the Edict of Nantes (1598), which guaranteed freedom of private worship and civil equality.[13]

Neuzeit[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Kolonialreich[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

France's pacification under Henry IV laid much of the ground for the beginnings of France's rise to European hegemony. France was expansive during all but the end of the seventeenth century: the French began trading in India and Madagascar, founded Quebec and penetrated the North American Great Lakes and Mississippi, established plantation economies in the West Indies and extended their trade contacts in the Levant and enlarged their merchant marine.

Dreizehnjähriger Krieg[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Henry IV's son Louis XIII and his minister (1624–1642) Cardinal Richelieu, elaborated a policy against Spain and the Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years' War (1618–48) which had broken out in Germany. After the death of both king and cardinal, the Peace of Westphalia (1648) secured universal acceptance of Germany's political and religious fragmentation, but the Regency of Anne of Austria and her minister Cardinal Mazarin experienced a civil uprising known as the Fronde (1648–1653) which expanded into a Franco-Spanish War (1653–59). The Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) formalised France's seizure (1642) of the Spanish territory of Roussillon after the crushing of the ephemeral Catalan Republic and ushered a short period of peace.[14]

Verwaltungsstrukturen[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The Ancien Régime, a French term rendered in English as "Old Rule", or simply "Former Regime", refers primarily to the aristocratic, social and political system of early modern France under the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties. The administrative and social structures of the Ancien Régime were the result of years of state-building, legislative acts (like the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts), internal conflicts and civil wars, but they remained a confusing patchwork of local privilege and historic differences until the French Revolution brought about a radical suppression of administrative incoherence.

Ludwig XIV., der Sonnenkönig[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

For most of the reign of Louis XIV (1643–1715), ("The Sun King"), France was the dominant power in Europe, aided by the diplomacy of Cardinal Richelieu's successor as the King's chief minister, (1642–61) Cardinal Jules Mazarin, (1602–61). Cardinal Mazarin oversaw the creation of a French Royal Navy that rivalled England's, expanding it from 25 ships to almost 200. The size of the Army was also considerably increased. Renewed wars (the War of Devolution, 1667–68 and the Franco-Dutch War, 1672–78) brought further territorial gains (Artois and western Flanders and the free county of Burgundy, previously left to the Empire in 1482), but at the cost of the increasingly concerted opposition of rival royal powers, and a legacy of increasing enormous national debt. An adherent of the theory of the "Divine Right of Kings", which advocates the divine origin of temporal power and any lack of earthly restraint of monarchical rule, Louis XIV continued his predecessors' work of creating a centralized state governed from the capital of Paris. He sought to eliminate the remnants of feudalism still persisting in parts of France and, by compelling the noble elite to regularly inhabit his lavish Palace of Versailles, built on the outskirts of Paris, succeeded in pacifying the aristocracy, many members of which had participated in the earlier "Fronde" rebellion during Louis' minority youth. By these means he consolidated a system of absolute monarchy in France that endured 150 years until the French Revolution.[15] McCabe says critics used fiction to portray the degraded Turkish Court, using "the harem, the Sultan court, oriental despotism, luxury, gems and spices, carpets, and silk cushions" as an unfavorable analogy to the corruption of the French royal court.[16]

The king sought to impose total religious uniformity on the country, repealing the "Edict of Nantes" in 1685. The infamous practice of "dragonnades" was adopted, whereby rough soldiers were quartered in the homes of Protestant families and allowed to have their way with them—stealing, raping, torturing and killing adults and infants in their hovels. Scores of Protestants then fled France, (following "Huguenots" beginning a hundred and fifty years earlier until the end of the 18th Century) costing the country a great many intellectuals, artisans, and other valuable people. Persecution extended to unorthodox Roman Catholics like the Jansenists, a group that denied free will and had already been condemned by the popes. Louis was no theologian and understood little of the complex doctrines of Jansenism, satisfying himself with the fact that they threatened the unity of the state. In this, he garnered the friendship of the papacy, which had previously been hostile to France because of its policy of putting all church property in the country under the jurisdiction of the state rather than that of Rome.[17]

In November 1700, the Spanish king Charles II died, ending the Habsburg line in that country. Louis had long waited for this moment, and now planned to put a Bourbon relative, Philip, Duke of Anjou, (1683–1746), on the throne. Essentially, Spain was to become a perpetual ally and even obedient satellite of France, ruled by a king who would carry out orders from Versailles. Realizing how this would upset the balance of power, the other European rulers were outraged. However, most of the alternatives were equally undesirable. For example, putting another Habsburg on the throne would end up recreating the grand multi-national empire of Charles V (1500–58), of the Holy Roman Empire (German First Reich), Spain, and the Two Sicilies which would also grossly upset the power balance. After nine years of exhausting war, the last thing Louis wanted was another conflict. However, the rest of Europe would not stand for his ambitions in Spain, and so the long War of the Spanish Succession began (1701–14), a mere three years after the War of the Grand Alliance, (1688–97, aka "War of the League of Augsburg") had just concluded.[18]

Abweichung und Revolution[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Unter der Herrschaft von Ludwig XV. (1715-1774) kam es durch die Kriege mit Großbritannien und Preußen im Siebenjährigen Krieg zu kostspieligen Versagen und dem Verlust Frankreichs nordamerikanischer Kolonien.

Gesamtheitlich gesehen kam es im Volk während des 18. Jahrhundert zu wachsender Unzufriedenheit mit der Monarchie. Ludwig XV. war durch seine sexuellen Exzesse, generelle Schwäche und dem Verlust von Kanada an Großbritannien ein höchst unbeliebter König. Die Literaturen der damaligen Philosophen sahen ein klares Zeichen von Unzufriedenheit im Volk, doch der König entschloss sich dieses zu ignorieren. Ludwig XV. starb 1774 an Pocken und sein Volk vergaß bei seinem Begräbnis nur wenig Tränen. Während Frankreich die in Großbritannien startende industrielle Revolution noch nicht zu spüren bekam, stieg in der französischen Mittelschicht der Frust an einem System dessen Herrscher dämlich, frivol, distanziert und veraltet erschienen, auch wenn der Feudalismus seit längerem bereits nicht mehr existierte.

Nach dem Tod von Ludwig XV 1774 bestieg sein Enkel den Thron. Auch wenn dieser ebenfalls anfänglich populär war, wurde er bereits im Jahre 1780 im französischen Volk höchst verabscheut. Er heiratete die österreichische Erzherzogin Marie Antoinette. Frankreichs Intervention in der amerikanischen Revolution stellte sich ebenfalls als sehr Teuer heraus.

Upon Louis XV's death, his grandson Louis XVI became king. Initially popular, he too came to be widely detested by the 1780s. He was married to an Austrian archduchess, Marie Antoinette. French intervention in the American War of Independence was also very expensive.[20]

With the country deeply in debt, Louis XVI permitted the radical reforms of Turgot and Malesherbes, but noble disaffection led to Turgot's dismissal and Malesherbes' resignation in 1776. They were replaced by Jacques Necker. Necker had resigned in 1781 to be replaced by Calonne and Brienne, before being restored in 1788. A harsh winter that year led to widespread food shortages, and by then France was a powder keg ready to explode.[21] On the eve of the French Revolution of July 1789, France was in a profound institutional and financial crisis, but the ideas of the Enlightenment had begun to permeate the educated classes of society.[22]

Begrenzte Monarchie[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

On September 3, 1791, the absolute monarchy which had governed France for 948 years was forced to limit its power and become a provisional constitutional monarchy. However, this too would not last very long and on September 21, 1792 the French monarchy was effectively abolished by the proclamation of the French First Republic. The role of the King in France in a Revolution gone berserk, was finally brought to a shattering end with the "guillotined" execution (beheading) in the public square of the "Place de la Revolution" of Louis XVI on Monday, January 21, 1793, which was followed by the infamous "Reign of Terror", mass executions and the provisional "Directory" form of republican government, and the eventual beginnings of twenty-five years of reform, upheaval, dictatorship, wars and renewal, with the various Napoleonic Wars.

Restauration[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The monarchy was briefly restored following the successive events of the French Revolution (1789–99), and the First French Empire under Napoleon (1804–1814/15) – when a coalition of European powers restored by arms the monarchy to the heirs of the House of Bourbon in 1814. However the deposed Emperor Napoleon I returned triumphantly to Paris from his exile in Elba and ruled France for a short period known as the Hundred Days.

When a Seventh European Coalition deposed Napoleon after the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the Bourbon monarchy was once again restored. The Count of Provence, brother of the Louis XVI, who was guillotined in 1793, was crowned as Louis XVIII, nicknamed "The Desired". Louis XVIII tried to conciliate the legacies of the Revolution and Ancien Régime both, also permitting the formation of a Parliament and constitutional Charter, usually "Charte octroyée" ("Granted Charter"). His reign was characterized by disagreements between the Doctrinaires, liberal thinkers who supported the Charter and rising bourgeoisie, and the Ultra-royalists, aristocrats and clergymen who totally refused the Revolution's heritage. However, the peace was granted by and statesmen like Talleyrand and the Duke of Richelieu, as well as King's moderation and prudent intervention.[23][24] In 1823, the liberal agitations in Spain brought to a French intervention on the royalist's side, who permitted to King Ferdinand VII to reject the Constitution.

However, the work of Louis XVIII was frustrated when, after his death in 16 September 1824, his brother the Count of Artois became King under the name of Charles X. Charles X was a strong reactionary who supported ultra-royalists and Catholic Church. Under his reign, the censorship of newspapers was reinforced, the Anti-Sacrilege Act passed and compensations to French Émigré were increased. However, there were also the intervention in the Greek Revolution and the first phase of the conquest of Algeria.

The absolutist tendencies of the King were disliked by Doctrinaire majority in the Chamber of Deputies, that in 18 March 1830 sent and cordial address to the King, remembering to him his vote on the Charter. However, Charles X received this address as a veiled threat, and in 25 July of the same year, he emanated the St. Cloud Ordinances, a plot to reduce Parliament powers and re-establish an absolute rule.[25] The opposition reacted with riots in Parliament and barricades in Paris, that erupteds in the July Revolution.[26] The King abdicated, such as his son the Prince Louis Antoine, in favour to his grandson Count of Chambord, nominatin his cousin the Duke of Orléans as regent.[27] However, it was too late, and the liberal opposition won over the monarchy.

Folgen und Julimonarchie[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

On 9 August 1830, the Chamber of Deputies elected Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans as "King of the French": for the first time since French Revolution, the King reigned on a people and not on a country. The Bourbon white flag was substituted with the French tricolour,[28] and a new Charter was introduced in August 1830.[29] The conquest of Algeria continued, and new settlements were established in the Gulf of Guinea, Gabon, Madagascar, Mayotte and also put Tahite under protectorate.[30]

However, despite the initial reforms, Louis Philippe was little different than his predecessors. The old nobility was replaced by urban bourgeoisie, and the working class was excluded from voting.[31] Louis Philippe appointed notable bourgeois as Prime Minister, like banker Casimir Périer, academic François Guizot, general Jean-de-Dieu Soult, and thus obtained the nickname of "Citizen King" (Roi Bourgeois). The July Monarchy was beset by corruption scandals and financial crisis. The opposition of the King was composed of Legitimists, supporting the Count of Chambord, Bourbon claimant to the Throne, and of Bonapartists and Republicans who fought against royalty and supported the principles of democracy. The King tried to suppress the opposition with censorship, but when the Campagne des banquets ("Banquets' Campaign") was repressed in February 1848,[32] riots and seditions erupted in Paris and later all France, resulting in the February Revolution. The National Guard refused to repress the rebellion, resulting in Louis Philippe abdicating and fleeing to England. On 24 February 1848, the monarchy was abolished and the Second Republic was proclaimed.[33] Despite later attempts to re-establish the Kingdom in the 1870s, during the Third Republic, the original French monarchy never returned.

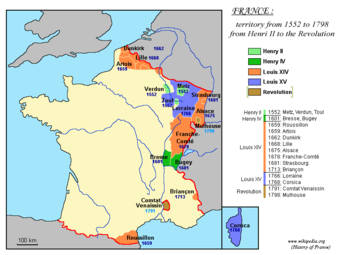

Territorien und Provinzen[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Siehe auch[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Einzelnachweise[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Literatur[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- François Bluche „L'Ancien Régime (Institutions et société)“ Éditeur: Éditions de Fallois, Collection:Le Livre de Poche La Flèche 1993 ISBN 2-253-06423-8

- Lucien Bély „La France moderne“ Éditeur Puf 1994 ISBN 978-2-13-059558-8

- Louis Halphen „Charlemagne et l'Empire carolingien“ Éditeur Albin Michel 1995 ISBN 2-226-07763-4.

- Pierre Miquel „Les Guerres de religions“ Éditeur Fayard 1997 ISBN 2-213-00826-4.