Benutzer:Shi Annan/Mukti Bahini

Mukti Bahini (bengalisch মুক্তি বাহিনী[1] meaning Freedom Fighters or Liberation Forces;[2] auch: Bangladesh Forces) ist ein volkstümlicher Begriff im Bengali für die guerrilla resistance movement formed by Bangladeshi military, paramilitary and later civilians during the country's War of Liberation in 1971.[3] Following the start of Operation Searchlight and the 1971 Bangladesh genocide committed by the Pakistan Army and pro-Pakistani paramilitary groups in East Pakistan, Bengali military and paramilitary units revolted across the territory. They were joined by thousands of Bengali civilians from a wide strata of society. The Bangladeshi Declaration of Independence was proclaimed from Chittagong by members of the Mukti Bahini on behalf of Prime Minister-elect Sheikh Mujibur Rahman- who was detained by the military junta in West Pakistan.

A formal military leadership took shape in April 1971 under the Provisional Government of Bangladesh. The military council was headed by General M. A. G. Osmani and eleven sector commanders. The Bangladesh Armed Forces were established on 4 April 1971. Aside from regular units like the East Bengal Regiment and the East Pakistan Rifles, the Mukti Bahini also consisted of the civilian Gonobahini (People's Force). The most prominent divisions of the Mukti Bahini were the Z Force led by Major Ziaur Rahman, the K Force led by Major Khaled Mosharraf and the S Force led by Major K M Shafiullah. Awami League student leaders formed militia units like the Mujib Bahini, the Kader Bahini and Hemayet Bahini. Communists led by Comrade Moni Singh and activists from the National Awami Party also operated several guerrilla battalions.

The Mukti Bahini has been compared with the French Resistance, the Yugoslav Partisans and the Viet Cong for its tactics and effectiveness. With guerrilla warfare, it secured control over large parts of the Bengali countryside. It conducted successful ambush and sabotage campaigns,[4] and included the nascent Bangladesh Air Force and the Bangladesh Navy. The Mukti Bahini received support from India, where people in its eastern and northeastern states shared a common Bengali ethnic and linguistic heritage with East Pakistan.

During the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the Mukti Bahini became part of the Bangladesh-India Allied Forces. It was instrumental in securing the Surrender of Pakistan and the liberation of Dacca and other cities in December 1971.

Etymology[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

All freedom fighters were broadly called Mukti Bahini(Freedom fighters). This was farther divided into two larger sections. One was Niomito Bahini (regular forces) which came from the paramilitary, military and police forces of East Pakistan. The second group was called Gonnobahini (People's forces) which were civilians. These names were assigned by the Government of Bangladesh. The Indians called Niomito Bahini as Mukti Fauj and Gonnobahini as Freedom Fighters.[10][11]

Background[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

East Pakistan campaigned against the imposition of Urdu as state language. The province was deprived of its equal share in resources and jobs in the civil and military administration. The demand for autonomy was ignored by the West Pakistani administration.[12] The two wings were a thousand mile apart and had very little in common except Islam. The Pashtun and Panjabis of West Pakistan would racially discriminate against Bengalis of East Pakistan.[13] The Awami League had won the majority in the 1970 Pakistan election. Sheikh Mujib as the leader of the Awami League was prevented from forming a government.[14] Bengali people who were the majority of the population of Pakistan were underrepresented in the government. In West Pakistan, Bengali's were viewed as "less Muslim". Bangla was the only language in Pakistan not written in Persian-Arabic alphabet. There was great suspicion in East Pakistan over the one unit scheme. The scheme turned all the administrative provinces of West Pakistan into one unit to counter the numerical superiority of East Pakistan.[15] Pakistan's unwillingness to give autonomy to East Bengal and Bengali nationalism are both cited as reasons for the separation.[16] The 1970 Bhola Cyclone had caused the death of 500,000 people and the infrastructure, transport and other services were severly damaged. The central government of Pakistan was blamed for the slow response and misuse of funds. It created resentment in the population of East Pakistan. The resentment allowed Awami League to win 167 of the 169 parliamentary seats in east pakistan and the majority in the 300 seat parliament of Pakistan. Yahya Khan hoped for a power sharing agreement between Mujib and Bhutto. Talks between them did not result in a solution. Mujib wanted full autonomy, Bhutto advised Yahya to break off talks. In march General Yahya Khan suspended the national assembly of Pakistan.[17]

Am 7. März 1971, Sheikh Mujib made his now famous speech in Ramna Race course (Suhrawardy Udyan) where he declared “The struggle this time is for our freedom. The struggle this time is for our independence”.[18] Television Channels in East Pakistan started broadcasting Rabindranath songs, which was a taboo in Pakistan and reduced programming from West Pakistan. Civilian interaction decreased with the army and they were increasingly seen as an occupying army. Local contractors stopped supplying the army.[19] Pakistan army had tried to disarm and dismiss the personnel of Bengali origin in East Pakistan Rifles, Police and the regular army. The Bengali officers did not obey and revolted, they attacked officers from West Pakistan.[20] The Pakistan army's crackdown on the civilian population had contributed to the revolt of East Pakistani soldiers. They moved to India and formed the central group of Mukti Bahini.[21] Sheikh Mujib on 26th March 1971 declared the independence of Bangladesh. On the same day, on a national broadcast Pakistan's president Yahya Khan declared Mujib a traitor.[22] [23] Pakistan army moved infantry and armored formation from West Pakistan to East Pakistan in preparation for the conflict.[24]

Früher Wiederstand[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

On 25th March, martial law was declared, Sheikh Mujib was arrested and Operation Searchlight started in East Pakistan. Foreign journalists were expelled and The Awami League was banned. Members of Awami league, East Pakistan Rifles, East Bengal Regiment and anyone deemed disloyal to Pakistan where attacked by the Pakistan army. The survivors of the pogrom would form the backbone of the Mukti Bahini.[25] When the Pakistan Army started the military crackdown on the Bengali population, they did not expect prolonged resistance.[26] Five battalions of the East Bengal Regiment mutinied and initiated the war for liberation of Bangladesh. On 27th March Major Ziaur Rahman declared Independence and moved out of Chittagong City.[27] The East Pakistan Rifles and the East Pakistan Police suffered heavy casualties while challenging the Pakistan Army in Dhaka, where West Pakistani forces began the 1971 Bangladesh genocide with the Dhaka University massacre. Civilians took control of arms depots in various cities. They began resisting Pakistani forces with the local weapons supply. Chittagong witnessed heavy fighting between rebel Bengali military units and Pakistani forces. The Bangladeshi Declaration of Independence was broadcast from Kalurghat Radio Station in Chittagong by Major Ziaur Rahman on behalf of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.[28]

Bengali forces took control of numerous districts in the initial months of the war, including Brahmanbaria, Faridpur, Barisal, Mymensingh, Comilla and Kushtia among others. With the support of the local population, many towns remained under the control of Bengali forces until April and May 1971. Notable engagements during this period included the Battle of Kamalpur, the Battle of Daruin and the Battle of Rangamati-Mahalchari waterway in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.[29]

In April 17, the Mujibnagar Government was formed. On April 18, Deputy High Commission of Pakistan in Kolkata defected and hoisted the flag of Bangladesh.[30]

In May, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto asked General Yahya Khan to hand over power in West Pakistan to his party. Yahya Khan refused on the grounds that doing so would support the view of Mukti Bahini and the Provisional Goverment of Bangladesh that East Pakistan was a colony of West Pakistan. Tensions were raised when Bhutto told his followers that by November he would either be in power or in jail.[31]

On 9th June, Mukti Bahini hijacked a car and launched a grenade attack on Dhaka Intercontinental Hotel, office of Pro-Junta Morning Post and the house of Golam Azam.[32]

Juli–November[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Juli[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

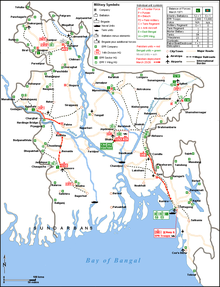

The Mukti Bahini divided the war zone into eleven sectors. The war strategy included a huge guerrilla force operating inside Bangladesh. On 27th march Major Ziaur Rahman declared independece of Bangladesh and battled his way out of Chittagong city. They targeted Pakistani installations through raids, ambush and sabotage paralyzing West Pakistani-controlled shipping, power plants, industries, railways and warehouses. The wide dispersion of Pakistani forces allowed Bengali guerrillas to target smaller groups of enemy soldiers. Groups of five to ten guerrillas were assigned with specific missions. Bridges, culverts, fuel depots and ships were destroyed to cripple the mobility of the Pakistan Army.[33] The Mukti Bahini failed in its Monsoon Offensive. Pakistani reinforcements successfully countered Bengali engagements in July. Attacks on border outposts in Sylhet, Comilla and Mymensingh met with limited success. The training period slackened the momentum of the Bangladesh Forces, which began to pick up after August.[34] After the monsoon, the Mukti Bahini became more effective. Indian army created a number of bases inside East Pakistan for the Mukti Bahini.[35] The Railways in East Pakistan were virtually shut down due to Mukti Bahini's sabotage. The provincial capital Dhaka had become a ghost town with gun fire and explosions heard throughout the day.[36]

August[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

After a visit to India in August 1971, Ted Kennedy believed that Pakistan was committing a genocide and Golam Azam called for the annexation of Assam in retaliation for Indian help to Mukti Bahini. He accused India of Shelling East Pakistan border areas on a daily basis. Oxfam predicted the deaths of over one hundred thousand children in refugee camps and more could die from food shortages in East Pakistan caused by the conflict.[37]

September[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Regular Mukti Bahini battalions were formed in September 1971.[38] Effectiveness of the Mukti Bahini increased, sabotage and ambushes were being carried out, harming the moral of the Pakistan army.[39]

October[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

From October, conventional Bangladesh Forces mounted various successful offensives. They captured 90 out of 300 border outposts. The Mukti Bahini intensified guerrilla attacks inside Bangladesh; while Pakistan increased reprisals on Bengali civilians.[40] The movement of Mukti Bahini in and out of East Pakistan and inside East Pakistan became more relaxed and common.[41]

November[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Indian involvement increased, with Indian artillery and Indian Air force providing direct cover to Mukti Bahini in some instances.[42] Attacks on infrastructure and the increase in the reach of the provisional government diminished the control of the Pakistan government. [43]

Air operations[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Die Bangladesh Air Force (BAF) was established on 28 September 1971 under the command of Air Commodore A K Khandker. It initially operated from a jungle airstrip near Dimapur in Nagaland. When taking over liberated territories, the Bangladesh Forces gained control of World War II airstrips in Lalmonirhat, Shalutikar, Sylhet and Comilla in November and December. The BAF launched "Kilo Flights" under the command of Squadron Leader Sultan Mahmud on 3 December 1971. Sorties by Otter DHC-3 aircraft destroyed Pakistani fuel supplies in Narayanganj and Chittagong. Targets included the Burmah Oil Refinery, numerous ships and oil depots.[44]

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The Bangladesh naval forces took shape in July. Operation Jackpot was launched by the Bangladesh Forces on 15 August 1971. Bengali naval commandos drowned 26 vessels of the Pakistan Navy in Mongla, Chittagong, Chandpur and Narayanganj.[45] Bengali commanders used their chief's wife in an ingenious way to pass through Pakistani check posts since they thought Pakistanis would not allow them to pass through if they did not have a woman with them, the operation was carried out hiding behind a woman. The operation was a major propaganda success for Bangladeshi forces, as it exposed to the international community the fragile hold of the West Pakistani occupation.[46] The nascent Bangladesh Navy commandos targeted patrol craft and ships carrying ammunition and commodities. It extensively mined the Passur River in the Sundarbans, which crippled the ability of Pakistani forces to operate from the Port of Mongla. The Mukti Bahini with Indian help acquired two vessels, Padma and Palash, which were retrofitted into gunboats with mine laying capabilities. They were mistakenly bombed by Indian Air force that resulted in the loss of the vessels and lives of Mukti Bahini and Indian personnel on board.[47] The developing Bangladesh Navy carried out attacks on ships and used sea mines to prevent supplies laden ships from docking in East Pakistani ports. Frogmen were deployed to damage ships.[48]

Organization[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

M. A. G. Osmani, a Bengali veteran of British Raj forces in World War II and Pakistan army, established the Bangladesh Armed Forces on 4 April 1971. The Provisional Government of Bangladesh placed all Bangladeshi forces under the command of Osmani, who was appointed defense minister with the ranks of Commander-in-Chief and a four star general. Osmani designated the composition of the Mukti Bahini into several divisions. It included the regular armed forces which covered the army, navy and air force; as well as special brigades like the Z Force. Paramilitary forces, including the East Pakistan Rifles and police, were designated as the Niyomito Bahini (Regular Forces). They were divided between forward battalions and sector troops. A further civilian force was raised and known as the Gonobahini (People's Forces). While the majority of the Gonobahini were lightly trained civilian brigades under military command; it also consisted of battalions set up by political activists from the pro-Western Awami League, the pro-Chinese socialist National Awami Party led by Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani and the pro-Soviet Communist Party of East Pakistan.[33]

The guerrilla movement was composed of three wings: well-armed Action Groups which took part in frontal attacks; military intelligence units; and guerrilla bases. The first conference of sector commanders was held in the week of 11–17 July 1971. Prominent sector commanders included defecting officers from the Pakistan Armed Forces, including Major Ziaur Rahman, Major Khaled Mosharraf, Major K M Shafiullah, Captain A. N. M. Nuruzzaman, Major Chitta Ranjan Dutta, Wing Commander M Khademul Bashar, Major Nazmul Huq, Major Quazi Nooruzzaman, Major Abu Osman Chowdhury, Major Abul Manzoor, Major M. A. Jalil, Major Abu Taher and Squadron Leader M. Hamidullah Khan.[49] The Mujib Bahini was led by Awami League youth leaders Sheikh Fazlul Huq Moni, Tofael Ahmed and Abdur Razzak. The Australian war veteran William A. S. Ouderland organized guerrilla warfare in Dacca and provided vital intelligence to the Bangladesh Forces. Left-wing politicians Kader Siddique, Hemayet Uddin and Moni Singh raised several guerrilla units.

The Independent Bangladesh Radio Station was one of the cultural wings of the Mukti Bahini. The Bangladesh liberation movement released five prominent propaganda posters which promoted the independence struggle irrespective of religion and gender. One of them famously portrayed Pakistan's military ruler Yahya Khan as a demon. The Mukti Bahini operated field hospitals, wireless stations, training camps and prisons.[50]

Equipment[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The Mukti Bahini benefited from the early control of Pakistani arms depots, which were overtaken by Bengali forces in March and April 1971. It purchased large quantities of military equipment through the flourishing arms market in Calcutta, including Italian howitzers, Allouette helicopters, Dakota DC-3 aircraft and Otter DHC-3 fighter planes. It received a limited arms supply from the Indian military, as New Delhi allowed the Bangladesh Forces to operate an independent weapons supply through Calcutta Port.[51] Personal of Mukti Bahini used Sten Gun, Lee–Enfield rifle and Indian made hand grenades.[52]

Bangladesh-India Allied Forces[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The launch of Operation Chengiz Khan by West Pakistan on North India finally drew India into the Bangladesh conflict. A joint command was established between Bangladeshi and Indian Forces. Three corps of the Indian Armed Forces were supported by three brigades of the Mukti Bahini and the vast Bengali guerrilla army. The Mukti Bahini and its supporters guided the Indian army and provided them with information about Pakistani troops movement.[53] They greatly outnumbered the three Pakistani army divisions of East Pakistan. The Battle of Sylhet, the Battle of Garibpur, the Battle of Boyra, the Battle of Hilli and the Battle of Kushtia were major joint engagements of Bangladeshi and Indian forces. The Allied Forces swiftly overran the country by selectively engaging or bypassing heavily defended strongholds. For example, the Meghna Heli Bridge airlifted Bangladeshi and Indian forces from Brahmanbaria to Narsingdi over Pakistani defenses in Ashuganj. The cities of Jessore, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Kushtia, Noakhali and Maulvi Bazar quickly fell to the Allied Forces. In the occupied Bengali capital Dhaka, the Pakistan Army and its supporting militias began the mass murder of Bengali intellectuals and professionals, in a final attempt to eliminate the Bengali intelligentsia. Both the allied forces and Pakistan army and its allies were accused of looting, rape and violence on the civilian population, belonging to their opponents.[54] The Mukti Bahini liberated most of Dhaka District by the second week of December. They surrounded the capital city. In the western theater, Indian forces advanced deep into Pakistani territory; while the Port of Karachi was subjected to a naval blockade by the Indian Navy. Pakistani generals succumbed to surrendering to the Allied Forces in Dhaka on 16 December 1971.[55]

Relations with India[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The genocide by Pakistani forces led to the outflow of 10 million Bengali refugees into neighbouring India, where the regions of West Bengal, Tripura and the Barak Valley shared strong ethnic, linguistic and cultural links with East Pakistan. The war sparked an unprecedented level of unity in the Bengali-speaking world. There was strong support for Bengalis and Mukti Bahini from the Indian media and Public.[56] India feared that if the movement for Bangladesh came to be dominated by communists then it would advarsly affect its own fight with the left-wing Naxalites. It also did not want the millions of refugees to be permanently stranded in India.[57]

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi authorized diplomatic, economic and military support to the Bangladesh Forces in April 1971.[29] The Provisional Government of Bangladesh established its secretariat in exile in Calcutta. The Indian Armed Forces provided substantial training and the use of its bases for the Bangladesh Forces. The Bangladesh liberation guerrillas operated training camps in the Indian states of Bihar, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Nagaland, Mizoram, Meghalaya, Tripura and West Bengal.[58][59] Mukti Bahini were allowed by India to cross the border at will.[60]

Some Mukti Bahini, especially those who served in the security services of Pakistan were suspicious of Indian involvement and wished to minimise its role. They also resented the formation of Mujib Bahini by India which was composed of Sheikh Mujib loyalists but was not under the command of Mukti Bahini or the provisional government of Bangladesh.[61]

Cold War politics[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Der genocide by Pakistani forces caused widespread international outrage against West Pakistan. In the United States, Democratic senator Ted Kennedy led a chorus of strong domestic criticism against the Nixon administration for ignoring the genocide of Bengalis in East Pakistan.

The Mukti Bahini enjoyed significant international public support. The Bangladeshi provisional government considered setting up an "International Brigade" with European and North American students.[51] French Minister of Cultural Affairs André Malraux vowed to fight on the battlefield alongside the Bangladesh Forces.[62]

The Nixon administration in the US enjoyed close ties with Pakistani military junta due to its policy of rapprochement with Communist China after the Sino-Soviet split. Pakistan's dictator Yahya Khan acted as a mediator between the US and China. However, Washington knew that the independence of East Pakistan was inevitable.[63] The Soviet Union threw its weight behind the Bangladesh Forces and India after being convinced of Pakistan's unwillingness for a political solution.[51] Separately, US efforts to woo China through Pakistan led to India signing friendship treaty with Moscow in August 1971. For India, the treaty was an important insurance policy against a possible Chinese intervention on the side of Pakistan. China had fought a brief war with India in 1962. Both the US and China, however, ultimately failed to mobilize adequate support for Pakistan.[58][59]

When India launched a two-front war against Pakistan in support of the Bangladesh Forces, US President Richard Nixon dispatched the USS Enterprise to the Bay of Bengal as Pakistan's defeat seemed imminent.[64] The White House was concerned over a possible full-scale Indian invasion of West Pakistan and Soviet domination of South Asia; both of which proved to be highly inaccurate. The Soviet Union sent a group of warships armed with nuclear missiles from Vladivostok, which trailed an American naval task force in the Indian Ocean. The Soviets also vetoed US and Chinese backed resolutions in the UN Security Council, calling for ceasefires favoring the Pakistani military.

Honours[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Bir Sreshtho (The Most Valiant Hero) is the highest military honor in Bangladesh and was awarded to seven Mukti Bahini fighters. They were Ruhul Amin, Mohiuddin Jahangir, Mostafa Kamal, Hamidur Rahman, Munshi Abdur Rouf, Nur Mohammad Sheikh and Matiur Rahman.

The other three gallantry awards in decreasing order of importance are Bir Uttom, Bir Bikrom and Bir Protik.[65]

Women[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Women had served in the Mukti Bahini during Bangladesh liberation war. The Mukti Bahini trained several female battalions for guerrilla warfare. Taramon Bibi is one of the two female wars heroes of the Bangladesh Liberation War. Captain Sitara Begum is noted for setting up field hospitals for injured Mukti Bahini fighters.[66] Professor Nazma Shaheen, University of Dhaka, and her sister were female freedom fighters in Mujib Bahini.[67]

Post-war[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The Mukti Bahini was succeeded by the Bangladesh Armed Forces, the Bangladesh Rifles and the Bangladesh Police. Civilian fighters were provided with numerous privileges, including reservations in government jobs and universities. The Bangladesh Freedom Fighters Assembly was formed to represent former guerrillas. The widespread availability of arms created serious law and order concerns for the Bangladesh government after the war. A few militia units are alleged to have taken part in reprisal attacks against the Urdu-speaking population following the Pakistani surrender. All units of the Mukti Bahini were ordered by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to surrender their arms by March 1972.

Criticism[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The Mukti Bahini has been accused of killing and raping Bihari citizens of East Pakistan who supported the Pakistan army. After the Liberation War of Bangladesh ended, Bihari people were forcefully relocated to refugee camps, were referred to as Stranded Pakistanis and denied citizenship of Bangladesh.[68]

Cultural legacy[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

The Mukti Bahini has been the subject of numerous artwork, literature, films and television productions.

See also[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

Einzelnachweise[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- ↑ Rounaq Jahan: Bangladesh in 1972: Nation Building in a New State. In: Asian Survey. 1. Februar 1973. vol. 13, 2: S. 31. doi=10.2307/2642736 Jstor.org

- ↑ Eyal Benvenisti: The International Law of Occupation. Oxford University Press 23. Februar 2012: S. 189– ISBN 978-0-19-163957-9 google books

- ↑ Muthiah Alagappa(hg.): Coercion and governance: the declining political role of the military in Asia. Stanford University Press, Stanford, Kalifornien 2001: S. 212. ISBN 0804742278

- ↑ Ahmed Abdullah Jamal: October–December 2008 |title=Mukti Bahini and the Liberation War of Bangladesh: A Review of Conflicting Views |url=http://www.cdrb.org/journal/2008/4/1.pdf |journal=Asian Affairs |publisher=Centre for Development Research, Bangladesh |volume=30 |issue=4 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150103014904/http://www.cdrb.org/journal/2008/4/1.pdf Archivlink]

- ↑ Don Oakley: East pakistan’s unheeded agony. The Daily Star. thedailystar.net The Nevada Daily Mail.

- ↑ Bhutan, not India, was first to recognize Bangladesh. In: The Times of India. PTI timesofindia.indiatimes.com.

- ↑ Mujibnagar: History’s first Bengali government. In: The Opinion Pages. opinion.bdnews24.com.

- ↑ Bhutan PM hands over message of recognition. bdnews24.com.

- ↑ Our Cruel Birth. In: The Daily Star. archive.thedailystar.net.

- ↑ Islam|first1=M. Rafiqul|title=A Tale of Millions: Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971|date=1981|publisher=Bangladesh Books International|pages=82}}

- ↑ Jamal|first1=Ahmed|title=MuktiI BahiniI and the Liberation war of Bangladesh : A Review of Conflicting Views|url=http://www.cdrb.org/journal/2008/4/1.pdf%7Cwebsite=CDRB%7Cpublisher=Asian affairs|accessdate=9 January 2016}}

- ↑ Said|first=Salim|title=Remembering the fall of Dhaka|url=http://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2015/12/16/comment/remembering-the-fall-of-dhaka/%7Cwebsite=pakistantoday.com%7Caccessdate=9 January 2016}}

- ↑ Saar|first1=John|title=Its War|url=https://books.google.com.bd/books?id=3z8EAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA30&dq=Mukti+Bahini&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiggfmuzZvKAhXUxI4KHWJEARkQ6AEIZjAN#v=onepage&q=Mukti%20Bahini&f=false%7Caccessdate=9 January 2016|work=Vol. 71, No. 24|agency=Life Magazine|publisher=Time Inc|date=10 December 1971

- ↑ Singh|first1=Jasbir|title=Combat diary|date=2010|publisher=Lancer|location=New Delhi|isbn=9781935501183|pages=225}}

- ↑ DeRouen|first1=Karl|title=Civil wars of the world major conflicts since World War II|date=2007|publisher=ABC-CLIO|location=Santa Barbara, Calif.|isbn=9781851099191|pages=594|edition=[Online-Ausg.]

- ↑ DeRouen|first1=Karl|title=Civil wars of the world major conflicts since World War II|date=2007|publisher=ABC-CLIO|location=Santa Barbara, Calif.|isbn=9781851099191|pages=597|edition=[Online-Ausg.]

- ↑ Oborne|first1=Peter|title=Wounded Tiger: A History of Cricket in Pakistan|publisher=Simon and Schuster|isbn=9780857200754 google books

- ↑ Qasmi|first1=Ali Usman|title=1971 war: Witness to history|url=http://herald.dawn.com/news/1153304%7Cwebsite=herald.dawn.com%7Caccessdate=9 January 2016|date=16 December 2015}}

- ↑ Roy|first1=Scott Gates, Kaushik|title=Unconventional warfare in South Asia: shadow warriors and counterinsurgency. 2014|publisher=Ashgate|location=Farnham|isbn=9781409437062|pages=116

- ↑ KrishnaRao|first1=K.V.|title=Prepare or perish : a study of national security|date=1991|publisher=Lancer Publ.|location=New Delhi|isbn=9788172120016|pages=168

- ↑ Singh|first1=Brig K. Kuldip|title=Indian Military Thought KURUKSHETRA to KARGIL and Future Perspectives|date=October 27, 2013|publisher=Lancer Publishers LLC|isbn=9781935501930|url=https://books.google.com.bd/books?id=rTG8AQAAQBAJ&pg=PT434&dq=Mukti+Bahini&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiggfmuzZvKAhXUxI4KHWJEARkQ6AEIUzAK#v=onepage&q=Mukti%20Bahini&f=false%7Caccessdate=9 January 2016

- ↑ East Pakistan Secedes, Civil war breaks out|url=http://www.thedailystar.net/freedom-in-the-air/stories/58422%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|publisher=Boston Globe|accessdate=9. Januar 2016.

- ↑ Civil war flares in East-Pakistan|url=http://www.thedailystar.net/freedom-in-the-air/stories/59515%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|publisher=The Deseret News|accessdate=9 January 2016}}

- ↑ Sharaf|first1=Samson Simon|title=1971: The plight of the viceroys|url=http://nation.com.pk/columns/09-Jan-2016/1971-the-plight-of-the-viceroys%7Cwebsite=The Nation|accessdate=9 January 2016}}

- ↑ McDermott|first1=Rachel Fell|last2=Gordon|first2=Leonard A.|last3=T. Embree|first3=Ainslie|last4=Pritchett|first4=Frances W.|last5=Dalton|first5=Dennis|title=Sources of Indian Tradition Modern India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.|date=2013|publisher=Columbia University Press|location=New York|isbn=9780231510929|pages=851|edition=Third edition.

- ↑ Pakistan Defence Journal, 1977, Vol 2, p2-3

- ↑ Roy|first1=Scott Gates, Kaushik|title=Unconventional warfare in South Asia: shadow warriors and counterinsurgency|date=2014|publisher=Ashgate|location=Farnham|isbn=9781409437062|pages=116}}

- ↑ McDermott|first1=Rachel Fell|last2=Gordon|first2=Leonard A.|last3=T. Embree|first3=Ainslie|last4=Pritchett|first4=Frances W.|last5=Dalton|first5=Dennis|title=Sources of Indian Tradition Modern India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.|date=2013|publisher=Columbia University Press|location=New York|isbn=9780231510929|pages=851|edition=Third edition.

- ↑ a b 17 December 2013 |title=Notable battles in the 11 Sectors |url=http://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2013/dec/17/notable-battles-11-sectors |newspaper=Dhaka Tribune}}

- ↑ Badrul Ahsan|first1=Syed|title=Diplomats carrying the torch in 1971|url=http://archive.thedailystar.net/newDesign/news-details.php?nid=182294%7Cwebsite=archive.thedailystar.net%7Caccessdate=10 January 2016}}

- ↑ Military Junta Dogs Pakistan.] http://www.thedailystar.net/freedom-in-the-air/stories/58668%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|publisher=Sarasota Journal|accessdate=10 January 2016}}

- ↑ Alam|first1=Habibul|title=Operation Hotel Intercontinental: “HIT & RUN”|url=http://www.thedailystar.net/freedom-in-the-air/stories/58940%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|accessdate=10 January 2016}}

- ↑ a b Rahman |first=Hasan Hafizur |date=1984 |script-title=বাংলাদেশের স্বাধীনতা যুদ্ধ, দলিলপত্রঃ দশম খণ্ড |trans-title=History of Bangladesh War of Independence Documents, Vol-10 |publisher=Hakkani Publishers |pages=1–3 |language=bn |isbn=984-433-091-2}}

- ↑ Roy |first=Mihir K. |date=1995 |title=War in the Indian Ocean |location=New Delhi |publisher=Lancer Publishers |page=154 |isbn=978-1-897829-11-0}}

- ↑ Weisburd|first1=A. Mark|title=Use of force: the practice of states since World War II|date=1997|publisher=Pennsylvania State Univ. Press|location=University Park, Pa.|isbn=978-0-271-01679-5

- ↑ Hossain|first1=Mokerrom|title=From Protest to Freedom: The Birth of Bangladesh A Book for the New Generation|date=2010|publisher=Shahitya Prakash|isbn=9780615486956|pages=246}}

- ↑ Pakistan Guilty of Genocide|url=http://www.thedailystar.net/freedom-in-the-air/stories/58267%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|publisher=Sydney Morning Herald|accessdate=10 January 2016}}

- ↑ Mazumder|first1=Shahzaman|title=Songs of Freedom|url=http://www.thedailystar.net/literature/songs-freedom-185875%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|accessdate=9 January 2016}}

- ↑ Hiranandani|first1=G.M.|title=Transition to triumph: history of the Indian Navy, 1965-1975|date=2000|publisher=Lancer Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=9781897829721|pages=129}}

- ↑ [http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,878969-4,00.html |title=The World: Bangladesh: Out of War, a Nation Is Born |date=20 December 1971 |work=TIME

- ↑ Zeitlin|first1=Arnold|title=East Pakistan Rebels Unafraid Of Being Caught Or Identified|url=http://www.thedailystar.net/freedom-in-the-air/stories/59359%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|publisher=Observer Reporter|accessdate=10 January 2016}}

- ↑ Sission|first1=Richard|last2=Rose|first2=Leo E.|title=War and secession: Pakistan, India, and the creation of Bangladesh|date=1991|publisher=University of California Press|location=Berkeley|isbn=9780520076655|pages=212}}

- ↑ Islam|first1=Asif|title=‘God was with me. But so were a lot of people’|url=http://www.dhakatribune.com/feature/2014/dec/16/%E2%80%98god-was-me-so-were-lot-people%E2%80%99%7Cwebsite=www.dhakatribune.com%7Caccessdate=9 January 2016}}

- ↑ [http://www.londoni.co/index.php/history-of-bangladesh?id=161%7Ctitle=Muktijuddho (Bangladesh Liberation War 1971) part 37 - Bangladesh Biman Bahini (Bangladesh Air Force or BAF) - History of Bangladesh|author=Administrator|work=Londoni}}

- ↑ Hossain |first=Abu Md. Delwar |year=2012 |chapter=Operation Jackpot |chapter-url=http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Operation_Jackpot |editor1-last=Islam |editor1-first=Sirajul |editor1-link=Sirajul Islam |editor2-last=Jamal |editor2-first=Ahmed A. |title=Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh |edition=Second |publisher=Asiatic Society of Bangladesh}}

- ↑ Yusuf|first1=Mostafa|title=Operation Jackpot, a glorious chapter of the 1971 Liberation War|url=http://bdnews24.com/bangladesh/2015/12/16/operation-jackpot-a-glorious-chapter-of-the-1971-liberation-war%7Cwebsite=bdnews24.com%7Caccessdate=9 January 2016}}

- ↑ Khan|first1=Tamanna|title=Indian war veterans relive '71 glory days|url=http://www.thedailystar.net/backpage/indian-war-veterans-relive-71-glory-days-189028%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|accessdate=9 January 2016}}

- ↑ Roy|first1=Mihir K.|title=War in the Indian Ocean|date=1995|publisher=Lancer Publishers|location=New Delhi|isbn=9781897829110|pages=169}}

- ↑ List of Liberation War Sectors and Sector Commanders of Bangladesh (Gazette Notification No.8/25/D-1/72-1378), Ministry of Defence, Government of Bangladesh, 15 December 1973

- ↑ Nabi|first1=Nuran Nabi with Mush|title=Bullets of ’71: a freedom fighter’s story|date=2010|publisher=AuthorHouse|location=Bloomington, IN|isbn=9781452043838|pages=220–223}}

- ↑ a b c Raghavan |first=Srinath |date=2013 |title=1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2S-wAQAAQBAJ |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-674-73127-1}}

- ↑ Alam|first1=Habibul|title=Operation Hotel Intercontinental: “HIT & RUN”|url=http://www.thedailystar.net/freedom-in-the-air/stories/58940%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|accessdate=10 January 2016}}

- ↑ Sachar|first1=Rajindar|title=Letting Bygones Be Bygones|url=http://www.outlookindia.com/article/letting-bygones-be-bygones/296302%7Cwebsite=www.outlookindia.com%7Caccessdate=9 January 2016}}

- ↑ Saikia|first1=Yasmin|title=Women, war, and the making of Bangladesh : remembering 1971|date=2011|publisher=Duke University Press|location=Durham, N.C|isbn=0822350386|pages=3

- ↑ Jacob |first=JFR |date=2000 |title=Surrender at Dacca: Birth of a Nation |location=Dhaka |publisher=University Press Ltd |isbn=984-05-1395-8}}

- ↑ Datta|first1=Antara|title=Refugees and borders in South Asia : the great exodus of 1971|date=2012|publisher=Routledge|location=New York|isbn=9780415524728|pages=28}}

- ↑ Datta|first1=Antara|title=Refugees and borders in South Asia : the great exodus of 1971|date=2012|publisher=Routledge|location=New York|isbn=9780415524728|pages=28}}

- ↑ a b Mizanur Rahman Shelley: 16 December 2012 |url=http://archive.thedailystar.net/suppliments/victory_day/2012/pg4.htm |title=Victory Day Special 2012 |work=The Daily Star}}

- ↑ a b Feroze |first=Shahriar |date=15 December 2014 |title=1971 — A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh |url=http://www.thedailystar.net/1971-a-global-history-of-the-creation-of-bangladesh-55388 |newspaper=The Daily Star}}

- ↑ Sagar|first1=Krishna Chandra|title=The war of the twins|date=1997|publisher=Northern Book Centre|location=New Delhi|isbn=9788172110826|pages=244}}

- ↑ Alagappa|first1=ed. by Muthiah|title=Coercion and governance : the declining political role of the military in Asia|date=2001|publisher=Stanford Univ. Press|location=Stanford, Calif.|isbn=9780804742276|pages=212}}

- ↑ [http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/04/28/bernard-henri-levy-andre-malraux-s-bangladesh-before-the-radicals.html |title=Bernard-Henri Levy: Andre Malraux's Bangladesh, Before the Radicals |work=The Daily Beast}}

- ↑ Khasru |first=B. Z. |date=23 November 2012 |title=Myths and Facts Bangladesh Liberation War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=jaSbAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT255 |publisher=Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd. |pages=255– |isbn=978-81-291-2542-2}}

- ↑ Mahfuz|first1=Asif|title=US Fleet in Bay of Bengal: A game of deception|url=http://archive.thedailystar.net/beta2/news/us-fleet-in-bay-of-bengal-a-game-of-deception/%7Cwebsite=The Daily Star|accessdate=10 January 2016}}

- ↑ The Bangladesh Gazette, 15 December 1973.

- ↑ [https://mukto-mona.com/Special_Event_/16December/courage161206.htm |title=The women in our liberation war: Tales of Endurance and Courage |last1=Amin |first1=Aasha Mehreen |last2=Ahmed |first2=Lavina Ambreen |last3=Ahsan |first3=Shamim |date=16 December 2006 |work=mukto-mona.com}}

- ↑ Gupta|first1=Jayanta|title=Women Mukti Joddhas recall guerrilla days - Times of India|url=http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/Women-Mukti-Joddhas-recall-guerrilla-days/articleshow/50212002.cms%7Cwebsite=The Times of India|accessdate=10 January 2016}}

- ↑ Mohiuddin|first1=Yasmeen Niaz|title=Pakistan: a global studies handbook|date=2007|publisher=ABC-Clio|location=Santa Barbara, Calif. [u.a.]|isbn=9781851098019|pages=174}}

Literatur[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]

- Ahmed |first=Helal Uddin |year=2012 |chapter=Mukti Bahini |chapter-url=http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Mukti_Bahini |editor1-last=Islam |editor1-first=Sirajul |editor1-link=Sirajul Islam |editor2-last=Jamal |editor2-first=Ahmed A. |title=Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh |edition=Second |publisher=Asiatic Society of Bangladesh}}

- Ayub |first=Muhammad |title=An Army, its Role and Rule: A History of the Pakistan Army from Independence to Kargil, 1967-1999 |location=Pittsburgh, PA |publisher=RoseDog Books |date=2005 |isbn=0-8059-9594-3}}

[[Category:National liberation armies]] [[Category:National liberation movements]] [[Category:Bangladesh Liberation War]] [[Category:Military history of Bangladesh]]