„Psychologische Unterschiede zwischen Männern und Frauen“ – Versionsunterschied

| [ungesichtete Version] | [ungesichtete Version] |

→Physical brain parameters: cite doi |

→Physical brain parameters: cite doi |

||

| Zeile 214: | Zeile 214: | ||

Studies have found many similarities but also differences in brain structure, neurotransmitters, and function.<ref name=Cosgrave2007>{{cite doi|10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001}}</ref> However, some argue that innate differences in the neurobiology of men and women have not been conclusively identified.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.005}}</ref><ref name="Fine" /> The relationship between sex differences in the brain and human behavior is a subject of controversy in psychology and society at large.<ref name="Fine" /><ref name="Jordan-Young">{{Cite document | last = Jordan-Young | first = Rebecca | title = Brain Storm: The Flaws in the Science of Sex Differences | publisher = Harvard University Press | year = 2010 | month= Sept. | isbn = 0674057309 | postscript = <!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}} }}</ref> |

Studies have found many similarities but also differences in brain structure, neurotransmitters, and function.<ref name=Cosgrave2007>{{cite doi|10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.001}}</ref> However, some argue that innate differences in the neurobiology of men and women have not been conclusively identified.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.03.005}}</ref><ref name="Fine" /> The relationship between sex differences in the brain and human behavior is a subject of controversy in psychology and society at large.<ref name="Fine" /><ref name="Jordan-Young">{{Cite document | last = Jordan-Young | first = Rebecca | title = Brain Storm: The Flaws in the Science of Sex Differences | publisher = Harvard University Press | year = 2010 | month= Sept. | isbn = 0674057309 | postscript = <!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. -->{{inconsistent citations}} }}</ref> |

||

A 2004 review in ''[[Nature Reviews Neuroscience]]'' observed that because hormones are easier to manipulate than genes, their effect on brain formation has had more research, and that the existing body of research "support the idea that sex differences in neural expression of X and Y genes significantly contribute to sex differences in brain functions and disease."<ref>{{cite doi|10.1038/nrn1494}}</ref> In the [[human brain]], a difference between sexes was observed in the [[gene transcription|transcription]] of the [[PCDH11X]]/Y gene pair unique to ''[[Homo sapiens]]''.<ref> |

A 2004 review in ''[[Nature Reviews Neuroscience]]'' observed that because hormones are easier to manipulate than genes, their effect on brain formation has had more research, and that the existing body of research "support the idea that sex differences in neural expression of X and Y genes significantly contribute to sex differences in brain functions and disease."<ref>{{cite doi|10.1038/nrn1494}}</ref> In the [[human brain]], a difference between sexes was observed in the [[gene transcription|transcription]] of the [[PCDH11X]]/Y gene pair unique to ''[[Homo sapiens]]''.<ref>{{cite doi|10.1007/s00439-006-0134-0}}</ref> |

||

Though statistically there are sex differences in white and [[gray matter]] percentage, this ratio is directly related to brain size, and these sex differences in gray and white matter percentage are caused by the average size difference between men and women.<ref name="Marner">{{cite doi|10.1002/cne.10714}}</ref><ref name="Gur">{{Cite pmid|10234034}}</ref> |

Though statistically there are sex differences in white and [[gray matter]] percentage, this ratio is directly related to brain size, and these sex differences in gray and white matter percentage are caused by the average size difference between men and women.<ref name="Marner">{{cite doi|10.1002/cne.10714}}</ref><ref name="Gur">{{Cite pmid|10234034}}</ref> |

||

Version vom 19. Februar 2012, 11:01 Uhr

Research on sex and psychology investigates cognitive and behavioral differences between men and women. This research employs experimental tests of cognition, which take a variety of forms. Tests focus on possible differences in areas such as IQ, spatial reasoning, and emotion.

Most IQ tests are constructed so that there are no overall score differences between females and males.[1] Areas where differences have been found include verbal and mathematical ability.[1]

Because social and environmental factors affect brain activity and behavior, where differences are found, it can be difficult for researchers to assess whether or not the differences are innate. Studies on this topic explore the possibility of social influences on how both sexes perform in cognitive and behavioral tests. Stereotypes about differences between men and women have been shown to affect a person's behavior.[2][3] Common stereotypes characterize men as aggressive and angry, and characterize women as emotionally sensitive and irrational.Vorlage:Citation needed

History

In Western countries in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, many people believed that inequality between the sexes could be attributed to biological differences.[2] Thomas Gisborne argued that women were naturally suited to domestic work and not spheres suited to men such as politics, science, or business. He argued that this was because women did not possess the same level of rational thinking that men did and had naturally superior abilities in skills related to family support.[4]

Nicolas Malebranche argued that abstraction was impossible for women, because of the "delicacy of the brain fibers."[2] In 1875, Herbert Spencer similarly argued that women were incapable of abstract thought and could not understand issues of justice, and only had the ability to understand issues of care.[5] In 1925, Sigmund Freud also concluded that women were less morally developed in the concept of justice, and, unlike men, were more influenced by feeling than rational thought.[5] Early brain studies comparing mass and volumes between the sexes concluded that women were intellectually inferior because they had smaller and lighter brains.[2] Many believed that the size difference caused women to be excitable, emotional, sensitive, and therefore not suited for political participation.[6] Today, others argue that brain size correlates with intelligence and/or personality.[2]

In the nineteenth century, whether men and women had equal intelligence was seen by many as a prerequisite for the granting of suffrage.[6] Leta Hollingworth argues that women were not permitted to realize their full potential, as they were confined to the roles of child-rearing and housekeeping. From the late twentieth century onwards, researchers have investigated the possibility of environmental factors in perceived sex differences.[5] Possible biological sex differences in intelligence have been discussed to determine whether disproportionate employment or payment favoring men is a manifestation of sexism or instead a reflection of innate aptitudes.[7]

During the early twentieth century, the scientific consensus held that gender plays no role in intelligence.[8] In his research, Psychologist Lewis Terman found "rather marked" differences on a minority of tests. For example, he found boys were "decidedly better" in arithmetical reasoning, while girls were "superior" at answering comprehension questions, though he concluded that gender plays no role in general intelligence. He also proposed that discrimination, denied opportunities, women's responsibilities in motherhood, or emotional factors may have accounted for the fact that few women had careers in intellectual fields. "[9]

Gender identity and socialization

An ongoing debate in psychology is the extent to which gender identity and gender-specific behavior is due to socialization (i.e. as opposed to in-born factors). The mainstream view is that both factors play a role, but the relative importance of each is contentious.Vorlage:Citation

Because of the pervasiveness of gender roles, it is difficult to execute a study which controls for the influence of such socialization. Individuals who are sex reassigned at birth offer an opportunity to see what happens when a child who is genetically one sex is raised as the other. The largest study of such individuals was conducted by Reiner & Gearhart on 14 children born with cloacal exstrophy and reassigned female at birth. Upon follow-up between the ages of 5 to 12, 8 of them identified as boys, and all of the subjects had at least moderately male-typical attitudes and interests, however these tests were not double blind as the parents (and often the subjects) knew the biological sex of children they were raising. [10]

According to Diane F. Halpern, some combination of social and biological factors may be at work in psychological sex differences.[11] She wrote in the preface of her 2000 book Sex Differences In Cognitive Abilitiess "Socialization practices are undoubtedly important, but there is also good evidence that biological sex differences play a role in establishing and maintaining cognitive sex differences, a conclusion I wasn't prepared to make when I began reviewing the relevant literature."

Intelligence

Vorlage:Human intelligence According to the report "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" in 1994 by the American Psychological Association, "Most standard tests of intelligence have been constructed so that there are no overall score differences between females and males."[1] When standardized IQ tests were first developed in the early 20th century, girls typically scored higher than boys up to age 14.[12] As testing methodology was revised, efforts were made to equalize gender performance.[12][13][14]

The American Psychological Association report said that differences were found in specific areas such as mathematics and verbal measures.[1]

The mean IQ scores between men and women vary little.[1][15][16][17][18] Studies that report variations in IQ between males and females find differences between 3-5 IQ points. Some studies have found a small male advantage on IQ tests, while others have found a small female advantage.[19][20][21]

Several meta-studies by Richard Lynn between 1999 and 2005 found mean IQ of men exceeding that of women by a range of 3-5 points.[19] [22][23] Lynn's findings were debated in a series of articles for Nature.[24][25] Jackson and Rushton found males aged 17–18 years had average of 3.63 IQ points in excess of their female equivalents.[26] A 2005 study by Helmuth Nyborg found an average advantage for males of 3.8 IQ points.[27] One study concluded that after controlling for sociodemographic and health variables, "gender differences tended to disappear on tests for which there was a male advantage and to magnify on tests for which there was a female advantage."[20] A study from 2007 found a 2-4 IQ point advantage for females in later life.[28] A 2001 report by the ETS found that "females in all racial/ethnic groups scored higher, on average, than males in reading, writing, and civics. There was an advantage found in science for Hispanic and White males. In mathematics, essentially no differences between males and females were found."[21] One study investigated the differences in IQ between the sexes in relation to age, finding that girls do better at younger ages but that their performance declines relative to boys with age.[29]

Kiefer and Sekaquaptewa proposed that a source of some women's underperformance and lowered perseverance in mathematical fields is these women's underlying "implicit" sex-based stereotypes regarding mathematical ability and association, as well as their identification with their gender.[30]

Different weightings or tests other than IQ, for instance general intelligence factor, may however be used in defining intelligence. A study by Colom et al. in 2002 showed that the difference observed is in "ability in general", not in "general ability", and that the average sex-difference favoring males must be attributed to specific group factors and test specificity.[31]

Variance

Some studies have identified IQ variance as a difference between males and females. Males tend to show higher variance on scores, though this may differ between countries.[32][33][34][35] Machin and Pekkarinen found higher variance in boys' than girls' results on mathematics and reading tests in most OECD countries.[36] A 2005 study by Ian Deary, Paul Irwing, Geoff Der, and Timothy Bates,[37] focusing on the ASVAB showed a significantly higher variance in male scores. The study also found a very small (d' ≈ 0.07, or about 7% of a standard deviation) average male advantage in g. A 2006 study by Rosalind Arden and Robert Plomin focused on children aged 2, 3, 4, 7, 9 and 10 and stated that there was greater variance "among boys at every age except age two despite the girls’ mean advantage from ages two to seven. Girls are significantly over-represented, as measured by chi-square tests, at the high tail and boys at the low tail at ages 2, 3 and 4. By age 10 the boys have a higher mean, greater variance and are over-represented in the high tail." [38]

Hyde and Metz[32] argue that boys and girls differ in the variance of their ability due to sociocultural factors. According to their analysis, which gender shows the greatest variance differs between countries: in some countries, such as the Netherlands, girls tend to have a greater variance than boys, whereas in others, such as the US, boys have the greater variance.

Mathematics

Large, representative studies of US students show that no sex differences in mathematics performance exist before secondary school.[3] During and after secondary school, historic sex differences in mathematics enrollment account for nearly all of the sex differences in mathematics performance.[3] However, a performance difference in mathematics on the SAT exists favoring males, though differences in mathematics course performance measures favor females.[3] With over 300 studies on the subject,[39] Stereotype threat has been shown to affect performance and confidence in mathematics of both males and females.[2][3]

In a 2008 study[40] paid for by the National Science Foundation in the United States, researchers found that "girls perform as well as boys on standardized math tests. Although 20 years ago, high school boys performed better than girls in math, the researchers found that is no longer the case. The reason, they said, is simple: Girls used to take fewer advanced math courses than boys, but now they are taking just as many."[41] However, the study indicated that, while on average boys and girls performed similarly, boys were overrepresented among the very best performers as well as among the very worst.[42][43]

In 1983, Benbow concluded that the study showed a large sex difference by age 13 and that it was especially pronounced at the high end of the distribution.[44] However, Gallagher and Kaufman criticized Benbow's and other reports finding males overrepresented in the highest percentages as not ensuring representative sampling.[3]

Some psychologists believe that many historical and current sex differences in mathematics performance may be related to boy's higher likelihood of receiving math encouragement than girls. Parents were, and sometimes still are, more likely to consider a son's mathematical achievement as being a natural skill while a daughter's mathematical achievement is more likely to be seen as something she studied hard for. This difference in attitude may contribute to girls and women being discouraged from further involvement in mathematics-related subjects and careers.[45]

Memory

The results from research on sex differences in memory are mixed and inconsistent, with some studies showing no difference, and others showing a female or male advantage.[46] Most studies have found no sex differences in short term memory, the rate of memory decline due to aging, or memory of visual stimuli.[46] Females have been found to have an advantage in recalling auditory and olfactory stimuli, experiences, faces, names, and the location of objects in space.[46][11] However, males show an advantage in recalling "masculine" events.[46]

Women show greater proficiency and reliance on distinctive landmarks for navigation while males rely on an overall mental map.[47][48] Studies by H. Stumpf and Richard Lynn have also demonstrated statistically significant medium- and short-term memory advantages in women. A study examining sex differences in performance on the California Verbal Learning Test found that males performed better on Digit Span Backwards and on reaction time, while females were better on short-term memory recall and Symbol-Digit Modalities Test.[20]

Spatial abilities

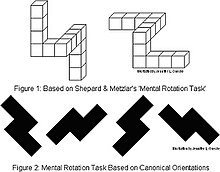

Many studies investigating the spatial abilities of men and women have found no significant differences,[49][50][51] though metastudies show a male advantage in mental rotation and assessing horizontality and verticality,[52][53] and a female advantage in spatial memory.[46][11] However, performance in mental rotation and similar spatial tasks is affected by gender expectations.[2][54] For example, studies show that being told before the test that men typically perform better, or that the task is linked with jobs like aviation engineering typically associated with men versus jobs like fashion design typically associated with women, will negatively affect female performance on spatial rotation and positively influence it when subjects are told the opposite.[55][56][57][58] Experiences such as playing video games also increase a person's mental rotation ability.[59][60]

Results from studies conducted in the physical environment are not conclusive about sex differences, with various studies on the same task showing no differences. For example, there are studies that show no difference in 'wayfinding'.[60] One study found men more likely to report having a good sense of direction and are more confident about finding their way in a new environment, but evidence does not support men having better map reading skills.[61] Women have been found to use landmarks more often when giving directions and when describing routes.[62] Additionally, a study concludes that women are better at recalling where objects are located in a physical environment.[61]

Researcher Simon Baron-Cohen has proposed the Empathizing-systemizing theory, and argues that spatial abilities are linked with the "male brain type" along with systemizing abilities, and is contrasted against the "female brain type", which he argues is linked with empathizing.[63] Baron-Cohen's theory and findings are controversial and many studies contradict the idea that baby boys and girls differ significantly in the way they learn or reason about objects' mechanical interactions.[64]

One study found that spatial ability in chromosomally abnormal individuals was related to whether they were raised as males or females, with those who were raised as males demonstrating superior spatial abilities. This study found no link between spatial ability and X or Y chromosomes, nor did it find a link between spatial ability and levels of androgen or estrogen.[65] A study from the University of Toronto supports the idea that possible gender differences in spatial cognition may be a result of experience rather than inherent ability. This study showed that differences in ability get reduced after playing video games requiring complex mental rotation. The experiment showed that playing such games creates larger gains in spatial cognition in females than males. [1]

Aggression

Vorlage:See also Although research on sex differences in aggression show that males are generally more likely to display aggression than females, how much of this is due to social factors and gender expectations is unclear.[53] Aggression is closely linked with cultural definitions of "masculine" and "feminine."[53] In some situations women show equal or more aggression than men; for example, women are more likely to use direct aggression in private, where other people cannot see them, and are more likely to use indirect aggression in public.[53]

Eagly and Steffen suggested in their meta-analysis of data on sex and aggression that beliefs about the negative consequences of violating gender expectations affect how both genders behave regarding aggression.[66] Men are more likely to be the targets of displays of aggression and provocation than females. Studies by Bettencourt and Miller show that when provocation is controlled for, sex differences in aggression are greatly reduced. They argue that this shows that gender-role norms play a large part in the differences in aggressive behavior between men and women.[67]

Psychologist Anne Campbell argues that females are more likely to use indirect aggression, and that "cultural interpretations have 'enhanced' evolutionarily based sex differences by a process of imposition which stigmatises the expression of aggression by females and causes women to offer exculpatory (rather than justificatory) accounts of their own aggression." [68] The relationship between testosterone and aggression is unclear, and a causal link has not been conclusively shown.[69][70][71][72] Some studies indicate that testosterone levels may be affected by environmental and social influences.[73]

Emotion

Women are stereotypically more emotional and men are stereotypically angrier.[74] [75] Studies examining actual emotional differences investigate the possible cultural and social influences, such as stereotypes, on results.

Scientists in the field distinguish between emotionality and the expression of emotion: Associate Professor of Psychology Ann Kring said, "It is incorrect to make a blanket statement that women are more emotional than men, it is correct to say that women show their emotions more than men.".[76]

In two studies by Kring, women were found to be more facially expressive than men when it came to both positive and negative emotions. These researchers concluded that men and women experience the same amount of emotion, but that women are more likely to express their emotions.

Women are known to have different shaped tear ducts than men as well as having more of the hormone prolactin (which is present in both blood and tears)[45]. While girls and boys cry at roughly the same amount at age 12, by age 18, women generally cry four times more than men[77], which could be explained by higher levels of prolactin.

In addition to biological differences between men and women, there are also documented differences in socialization that could contribute to sex differences in emotion and to differences in patterns of brain activity. An American Psychological Association article states that, “boys are generally expected to suppress emotions and to express anger through violence, rather than constructively”.[78] A child development researcher at Harvard University[78] argues that boys are taught to shut down their feelings, such as empathy, sympathy and other key components of what is deemed to be pro-social behavior. According to this view, differences in emotionality between the sexes are theoretically only socially-constructed, rather than biological.

When measured with an affect intensity measure, women reported greater intensity of both positive and negative affect than men. Women also reported a more intense and more frequent experience of affect, joy, and love but also experienced more embarrassment, guilt, shame, sadness, anger, fear, and distress. Experiencing pride was more frequent and intense for men than for women.[74]

Women are more likely than men to show unipolar depression, but this is not caused by biological factors such as genes or hormones. It may instead be due to the different coping mechanisms men and women develop from being raised differently.[79]

Studies that measure facial expression by the use of electromyography recordings show that women are more adequately able to manipulate their facial expressions than men. Men, however can inhibit their expressions better than females when cued to do so. In the observer ratings women’s facial expressions are easier to read as opposed to men’s except for the expression of anger.[74]

When lacking substantial emotion information they can base judgments on, people tend to rely more on gender stereotypes. Results from a study conducted by Robinson and colleaguesVorlage:Ref implied that gender stereotypes as more influential when judging others' emotions in a hypothetical situation. Also, with minimal or no available relevant emotional information, men and women depend on gender stereotypes to fill in lacking information.

Context also determines a man or woman's emotional behavior. Context-based emotion norms, such as feeling rules or display rules, "prescribe emotional experience and expressions in specific situations like a wedding or a funeral," (290)[74] independent of the person's gender. In situations like a wedding or a funeral, the activated emotion norms apply to and constrain every person in the situation. Gender differences are more pronounced when situational demands are very small or non-existent as well as ambiguous situations. During these situations, gender norms "are the default option that prescribes emotional behavior." (291)[74]

Empathy

While women perform better than men in tests involving emotional interpretation,[80][81][82][83] such as understanding facial expressions, and empathy, studies have shown that this is related to the subject's perceived gender identity and gender expectations.[2] Additionally, culture impacts gender differences in the expression of emotions. This may be explained by the different social roles men and women have in different cultures, and by the status and power men and women hold in different societies, as well as the different cultural values various societies hold.[74]

Some studies have found no differences in empathy between men and women, and suggest that perceived gender differences are the result of motivational differences.[84][85]

Some researchers argue that because differences in empathy disappear on tests where it is not clear that empathy is being studied, men and women do not differ in ability, but instead in how empathetic they would like to appear to themselves and others.[2][86]

One study showed that at birth girls gaze longer at a face, whereas suspended mechanical mobiles, rather than a face, keep boys' attention for longer, though this study has been criticized as having methodological flaws.[2]

In a study where researchers wanted to concentrate on nonverbal expressions by just looking at the eyebrows, lips, and the eyes, participants read certain cue cards that were either negative or positive and recorded the responses. In the results of this experiment it is shown that feminine emotions happen more frequently and have a higher intensity in women than men. In relation to the masculine emotions, such as anger, the results are flipped and the women’s frequency and intensity is lower than the men’s.Vorlage:Ref In imagined frightening situations, such as being home alone and witnessing a stranger walking towards your house, women reported greater fear. Women also reported more fear in situations that involved "a male's hostile and aggressive behavior" (281)Vorlage:Ref In anger-eliciting situations, women communicated more intense feelings of anger than men. Women also reported more intense feelings of anger in relation to terrifying situations, especially situations involving a male protagonist.Vorlage:Ref

Problems with research

Studies of psychological gender differences are controversial and subject to error. Many small-scale studies report differences that are not repeated in larger studies. Self-report questionnaires are subject to bias, particularly if the subjects are told that the questionnaire is testing for gender roles. It is also possible that commentators may exaggerate or downplay differences for ideological reasons.[2]

Physical brain parameters

Vorlage:See also Studies have found many similarities but also differences in brain structure, neurotransmitters, and function.[87] However, some argue that innate differences in the neurobiology of men and women have not been conclusively identified.[88][2] The relationship between sex differences in the brain and human behavior is a subject of controversy in psychology and society at large.[2][89]

A 2004 review in Nature Reviews Neuroscience observed that because hormones are easier to manipulate than genes, their effect on brain formation has had more research, and that the existing body of research "support the idea that sex differences in neural expression of X and Y genes significantly contribute to sex differences in brain functions and disease."[90] In the human brain, a difference between sexes was observed in the transcription of the PCDH11X/Y gene pair unique to Homo sapiens.[91]

Though statistically there are sex differences in white and gray matter percentage, this ratio is directly related to brain size, and these sex differences in gray and white matter percentage are caused by the average size difference between men and women.[92][93] [94][95] Others argue that these differences remains after controlling for brain weight.[87]

Differences in brain physiology between sexes do not necessarily relate to differences in intellect. Haier et al. found in a 2004 study that: "Men and women apparently achieve similar IQ results with different brain regions, suggesting that there is no singular underlying neuroanatomical structure to general intelligence and that different types of brain designs may manifest equivalent intellectual performance.[96]

While men's brains are an average of 10–15% larger and heavier than women's brains, some researchers propose that the ratio of brain to body size does not differ between the sexes.[97][98] However, some argue that since brain-to-body-size ratios tend to decrease as body size increases, a sex difference in brain-weight ratios still exists between men and women of the same size. A 1992 study of 6,325 Army personnel found that men's brains had an average volume of 1442 cm3, while the women averaged 1332 cm3. These differences were shown to be smaller but to persist even when adjusted for body size measured as body height or body surface, such that women averaged 100g less brain mass than men of equal size.[99]

Despite these findings, there still remains no clear relationship between physical brain measurement and functional capacity. In 2002, Faverjon et al. suggested that physical studies of the brain in predicting intelligence are largely arbitrary due to the inherent neuroplasticity of the organ and the multitude of ways that brain function can be influenced by the stimulating quality of the environment and hormonal influences.[100]

Larry Cahill argues that neurobiological differences between men and women exist in brain lateralization and emotional processing. [101][102][103] Fine criticizes his conclusions as failing to account for size differences and failing to consider the possibility of environenmental influences on brain activity, and in some cases relying on research about rats instead of humans.[2]

Women show a significantly greater activity in the left amygdala when encoding and remembering emotionally arousing pictures (such as mutilated bodies.[104])

Men and women tend to use different neural pathways to encode stimuli into memory. While highly emotional pictures were remembered best by all participants in one study, as compared to emotionally neutral images, women remembered the pictures better than men. This study also found greater activation of the right amygdala in men and the left amygdala in women.[105]

On average, women use more of the left hemisphere when shown emotionally arousing images, while men use more of their right hemisphere. Women also show more consistency between individuals for the areas of the brain activated by emotionally disturbing images.[104]

One study of 12 men and 12 women found that more areas in the brains of women were highly activated by emotional imagery, though the differences may have been due to the upbringing of the test participants.[106]

When women are asked to think about past events that made them angry, they show activity in the septum in the limbic system; this activity is absent in males. In contrast, men's brains show more activity in the limbic system when asked to identify happy or sad male and female faces. Men and women also differ in their ability to recognize sad female faces: in one study, men recognized 70%, while women recognized 90%.[107]

Responses to pain also reveal sex differences. In women, the limbic system, which is involved in the processing of emotions, shows greater activity in response to pain. In men, cognitive areas of the brain, which are involved in analytical processing, show higher activity in response to pain.[108] This indicates a connection between pain-responsive brain regions and emotional regions in women.

Theories

The possibility of testosterone and other androgens as a cause of sex differences in psychology has been a subject of study. Adult women who were exposed to unusually high levels of androgens in the womb due to a condition called congenital adrenal hyperplasia score significantly higher on tests of spatial ability.[109] Girls with this condition play more with "boys' toys" and less with "girls' toys" than unaffected controls.[110]

Many studies find positive correlations between testosterone levels in normal males and measures of spatial ability.[111] However, the relationship is complex.[112][113]

A proposed hypothesis is that men and women evolved different mental abilities to adapt to their different roles in society.[114][115] This explanation suggests that men may have evolved greater spatial abilities as a result of certain behaviors, such as navigating during a hunt.[116] Similarly, this hypothesis suggests that women may have evolved to devote more mental resources to remembering locations of food sources in relation to objects and other features in order to gather food,[117] as well as understanding and tracking relationships and reading others' emotional states in order for them to be able to better care for children and understand their social situation.[116] However, recent research suggests that the sexual division of labor developed relatively recently and that gender roles were not always the same in early-human cultures, contradicting the theory that each sex is naturally predisposed to different types of work.[118]

The book Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference published in 2010 by Cordelia Fine provides a critical analysis of hundreds of recent studies on sex and intelligence. She argues that there is currently no scientific evidence for innate biological differences between men and women's minds, and that cultural and societal beliefs contribute to commonly perceived sex differences.[119]

Controversies

In January 2005, Lawrence Summers, president of Harvard University, unintentionally provoked a public controversy when several attendees discussed with reporters some statements he made during his lunchtime presentation at an economics conference at the National Bureau of Economic Research.[120][121][122] In analyzing the disproportionate numbers of men over women in high-end science and engineering jobs, he suggested that, after the conflict between employers' demands for high time commitments and women's disproportionate role in the raising of children, the next most important factor might be the above-mentioned greater variance in intelligence among men than women, and that this difference in variance might be intrinsic,[120] adding that he "would like nothing better than to be proved wrong." The controversy generated a great deal of media attention; it contributed to the resignation of Summers the following year,[123] and led Harvard to commit $50 million to the recruitment and hiring of women faculty.[124] Stimulated by this controversy, in May 2005, Harvard University psychology professors Steven Pinker and Elizabeth Spelke debated "The Science of Gender and Science".[125]

In 2006, Danish psychologist and intelligence researcher Helmuth Nyborg was temporarily suspended from his position at Aarhus University, after being accused of scientific misconduct in relation to the documentation of a peer-reviewed paper appearing in the journal Personality and Individual Differences, in which he showed a 3.15-point IQ advantage of men over women.[27] This led to a review of his work by an investigative committee. Nyborg was defended — and the university criticized — by other researchers in the intelligence field.[45][126]

See also

- Neuroscience and intelligence

- Height and intelligence

- Fertility and intelligence

- Heritability of IQ

- Race and intelligence

Other:

References

Bibliography

- Born, M. P.; Bleichrodt, N.; van der Flier, H.: Cross-cultural comparison of sex-related differences on intelligence tests. In: Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 18. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, 1987, S. 283–314, doi:10.1177/0022002187018003002.

- Colom, R.; García, L.F.; Juan-Espinosa, M.; Abad, F.: Null Sex Differences in General Intelligence: Evidence from the WAIS-III. In: Spanish Journal of Psychology. 5. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 2002, S. 29–35, PMID 12025362 (ucm.es [PDF]).

- Haier, R.J.; Benbow, C.P.: Sex differences and lateralization in temporal lobe glucose metabolism during mathematical reasoning. In: Dev Neuropsychol. 11. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, 1995, S. 405–14, doi:10.1080/87565649509540629.

- Lynn, Richard; Irwing, P.; Cammock, T.: Sex differences in general knowledge. In: Intelligence. 30. Jahrgang, 2002, S. 27–40, doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(01)00064-2.

- Lynn, Richard: Sex differences in intelligence and brain size: a developmental theory. In: Intelligence. 27. Jahrgang, 1999, S. 1–12, doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00009-4.>>>

Vorlage:Human group differences

- ↑ a b c d e Ulric Neisser, Boodoo, Gwyneth; Bouchard, Thomas J., Jr.; Boykin, A. Wade; Brody, Nathan; Ceci, Stephen J.; Halpern, Diane F.; Loehlin, John C.; Perloff, Robert; Sternberg, Robert J.; Urbina, Susana: Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns. In: American Psychologist. 51. Jahrgang, Nr. 2. American Psychological Association, Februar 1996, S. 77–101, doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.77 (apa.org).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Fine, CordeliaDelusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference 2010

- ↑ a b c d e f Ann M. Gallagher, James C. Kaufman, Gender differences in mathematics: an integrative psychological approach, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0521826055, 9780521826051

- ↑ Thomas Gisborne, An enquiry into the duties of the female sex, Printed by A. Strahan for T. Cadell jun. and W. Davies, 1801

- ↑ a b c Judith Worell, Encyclopedia of women and gender: sex similarities and differences and the impact of society on gender, Volume 1, Elsevier, 2001, ISBN 0122272463, 9780122272462

- ↑ a b Margarete Grandner, Austrian women in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: cross-disciplinary perspectives, Berghahn Books, 1996, ISBN 1571810455, 9781571810458

- ↑ Fausto-Sterling, Anne (1992). Myths of Gender: biological theories about women and men. ISBN 0465047920

- ↑ Burt, C. L.; Moore, R. C. (1912). "The mental differences between the sexes". Journal of Experimental Pedagogy, 1, 273–284, 355–388.

- ↑ Terman, Lewis M. (1916). The measurement of intelligence: an explanation of and a complete guide for the use of the Stanford revision and extension of the Binet-Simon intelligence scale. Houghton Mifflin, Boston. OCLC 186102

- ↑ Reiner & Gearhart's NEJM Study on Cloacal Exstrophy - Review by Vernon Rosario, M.D., Ph.D.

- ↑ a b c Halpern, Diane F., Sex differences in cognitive abilities, Psychology Press, 2000, ISBN 0805827927, 9780805827927

- ↑ a b Elizabeth A. Rider: Our Voices: Psychology of Women. Wadsworth, Belmont, California 2000, ISBN 0-534-34681-2, S. 202.

- ↑ Archer, John, Barbara Bloom Lloyd, Sex and gender, Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0521635330, 9780521635332

- ↑ Sternberg, Robert J., Handbook of intelligence, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0521596483

- ↑ Roy F. Baumeister: Social psychology and human sexuality: essential readings. Psychology Press, 2001, ISBN 1841690198, 9781841690193(?!).

- ↑ Roy F. Baumeister: Is there anything good about men?: how cultures flourish by exploiting men. Oxford University Press, 2010, ISBN 019537410X, 9780195374100(?!).

- ↑ Larry V. Hedges, Nowell, Amy: Sex Differences in Mental Test Scores, Variability, and Numbers of High-Scoring Individuals. In: Science. 269. Jahrgang, Nr. 5220, 1995, S. 41–45, doi:10.1126/science.7604277, PMID 7604277, bibcode:1995Sci...269...41H.

- ↑ Colom, R., Garcia, L. F., Juan-Espinosa, M., & Abad, F. (2002). Null sex differences in general intelligence: Evidence from the WAIS-III. Spanish Journal of Psychology 5:29–35.

- ↑ a b Lynn, Richard: Sex differences in intelligence and brain size: a developmental theory. In: Intelligence. 27. Jahrgang, 1999, S. 1–12, doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00009-4.

- ↑ a b c Anthony F. Jorm, Anstey, Kaarin J.; Christensen, Helen; Rodgers, Bryan: Gender differences in cognitive abilities: The mediating role of health state and health habits. In: Intelligence. 32. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, S. 7–23, doi:10.1016/j.intell.2003.08.001.

- ↑ a b Differences in the Gender Gap: Comparisons Across Racial/Ethnic Groups in Education and Work. Educational Testing Service; Research Division: Policy Information Center, abgerufen im Jahr 2008.[2].

- ↑ Lynn, R., & Irwing, P.: Sex differences on the Progressive Matrices: A meta-analysis. In: Intelligence. 32. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, 2004, S. 481−498, doi:10.1016/j.intell.2004.06.008.

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite pmid

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ Douglas N. Jackson, Rushton, J. Philippe: Males have greater g: Sex differences in general mental ability from 100,000 17- to 18-year-olds on the Scholastic Assessment Test. In: Intelligence. 34. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, S. 479–486, doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.03.005.

- ↑ a b Nyborg, H.: Sex-related differences in general intelligence g, brain size, and social status. In: Personality and Individual Differences. 39. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, August 2005, S. 497–509, doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.12.011.

- ↑ Keith et al., M Reynolds, P Patel, K Ridley: Sex differences in latent cognitive abilities ages 6 to 59: Evidence from the Woodcock–Johnson III tests of cognitive abilities. In: Intelligence. 36. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, 2007, S. 502–525, doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.11.001 (iapsych.com [PDF]).

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ Implicit Stereotypes and Gender Identification May Affect Female Math Performance. Science Daily (Jan 24, 2007).

- ↑ Colom, R.; Garcia, L.F.; Juan-Espinosa, M.; Abad, F.: Null Sex Differences in General Intelligence: Evidence from the WAIS-III. In: Spanish Journal of Psychology. 5. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 2002, S. 29–35, PMID 12025362 (ucm.es [PDF]).

- ↑ a b Hyde, J.S.; Metz, J.E.: Gender, culture, and mathematics performance. In: PNAS. 106. Jahrgang, Nr. 22, 2009, S. 8801–7, doi:10.1073/pnas.0901265106, PMID 19487665, PMC 2689999 (freier Volltext) – (pnas.org).

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite pmid

- ↑ Robin McKie: Who has the bigger brain? In: The Guardian, November 6, 2005

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite pmid

- ↑ Machin, S.; Pekkarinen, T.: Global Sex Differences in Test Score Variability. In: Science. 322. Jahrgang, Nr. 5906, 2008, S. 1331–2, doi:10.1126/science.1162573, PMID 19039123 (sciencemag.org).

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ http://www.arizona.edu/sites/arizona.edu/files/users/user14/Stereotype%20Threat%20Overview.pdf

- ↑ Hyde, J., Lindberg, S., Linn, M., Ellis, A., & Williams, C.: Diversity: Gender Similarities Characterize Math Performance. In: Science. 321. Jahrgang, Nr. 5888, 2008, S. 494–5, doi:10.1126/science.1160364, PMID 18653867.

- ↑ Lewin, Tamar (July 25, 2008)."Math Scores Show No Gap for Girls, Study Finds", The New York Times.

- ↑ Winstein, Keith J. (July 25, 2008). "Boys' Math Scores Hit Highs and Lows", The Wall Street Journal (New York).

- ↑ Camilla Persson Benbow, David Lubinski, Daniel L. Shea, Hossain Eftekhari-Sanjani: Sex Differences in Mathethematical Reasoning Ability at Age 13: Their Status 20 Years Later. In: Psychological Science. 11. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, November 2000, S. 474–480, doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00291, PMID 11202492 (vanderbilt.edu [PDF; abgerufen am 25. Mai 2008]).

- ↑ Camilla Persson Benbow, Stanley Julian C: 'Sex Differences in Mathematical Reasoning Ability: More Facts'. In: Science. 222. Jahrgang, Nr. 4627, 1983, S. 1029–1031, doi:10.1126/science.6648516, PMID 6648516 (sciencemag.org).

- ↑ a b c Wood, Samual; Wood, Ellen; Boyd Denise (2004). "World of Psychology, The (Fifth Edition)" , Allyn & Bacon ISBN 0205361374

- ↑ a b c d e Ellis, Lee, Sex differences: summarizing more than a century of scientific research, CRC Press, 2008, ISBN 0805859594, 9780805859591

- ↑ Kimura, Doreen (May 13, 2002). "Sex Differences in the Brain: Men and women display patterns of behavioral and cognitive differences that reflect varying hormonal influences on brain development", Scientific American.

- ↑ National Geographic - My Brilliant Brain "Make Me a Genius" http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-6378985927858479238#

- ↑ Corley, DeFries, Kuse, Vandenberg. 1980. Familial Resemblance for the Identical Blocks Test of Spatial Ability: No Evidence of X Linkage. Behavior Genetics.

- ↑ Julia A. Sherman. 1978. Sex-Related Cognitive Differences: An Essay on Theory and Evidence Springfield.

- ↑ Developmental Influences on Adult Intelligence: The Seattle Longitudinal Study

- ↑ Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns

- ↑ a b c d Joan C Chrisler: Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology. Springer, 2010, ISBN 1441914641, 9781441914644(?!).

- ↑ Paula J. Caplan, Gender differences in human cognition, Oxford University Press US, 1997, ISBN 0195112911, 9780195112917

- ↑ Newcombe, N. S. (2007). Taking Science Seriously: Straight thinking about spatial sex differences. In S. Ceci & W. Williams (eds.), Why aren't more women in science? Top researchers debate the evidence (pp. 69-77). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- ↑ Sharps M.J., Price J. L., Williams J K.: Spatial cognition and gender: Instructional and stimulus influences on mental image rotation performance. In: Psychology of Women Quarterly,. 18. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, 1994, S. 413–425, doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1994.tb00464.x.

- ↑ McGlone M. S., Aranson J.: Stereotype threat. identity salience, and spatial reasoning. In: Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 27. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, 2006, S. 486–493, doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2006.06.003.

- ↑ Hausmann M., Schoofs D., Rosenthal H. E. S., Jordan K.: Interactive effects of sex hormones and gender stereotypes on cognitive sex differences--A psychobiological approach. In: Psychoneuroendocrinology. 34. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, 2009, S. 389–401, doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.09.019, PMID 18992993.

- ↑ Cherney I.D.: Mom, let me play more computer games: They improve my mental rotation skills. In: Sex Roles. 59. Jahrgang, Nr. 11–12, 2008, S. 776–786, doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9498-z.

- ↑ a b Devlin, Ann Sloan, Mind and maze: spatial cognition and environmental behavior, Praeger, 2001, ISBN 0275967840, 9780275967840

- ↑ a b Montello, Daniel R., Kristin L. Lovelace, Reginald G. Golledge, and Carole M. Self. 1999. Sex-related differences and similarities in geographic and environmental spatial abilities. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 89 (3):515.

- ↑ Miller, Leon K., and Viana Santoni. 1986. Sex differences in spatial abilities: Strategic and experiential correlates. Acta Psychologica 62 (3):225-235.

- ↑ Simon Baron-Cohen: The Extreme-Male-Brain Theory of Autism.

- ↑ Spelke ES: Sex differences in intrinsic aptitude for mathematics and science?: a critical review. In: Am Psychol. 60. Jahrgang, Nr. 9, 2005, S. 950–8, doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.9.950, PMID 16366817 (harvard.edu [PDF; abgerufen am 6. April 2009]).

- ↑ Bock and Kolakowski. 1973. Further Evidence of Sex-linked Major-Gene Influence on Human Spatial Visualizing Ability American Journal of Human Genetics

- ↑ Eagly, AH, & Steffen, V. (1986). Gender and aggressive behavior: A meta-analytic review of the social psychological literature. Psychological Bulletin

- ↑ Bettencourt, BA, & Miller, N. (1996). Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: A metaanalysis. Psychological Bulletin

- ↑ Anne Campbell: Staying alive: evolution, culture, and women's intrasexual aggression. In: Behav Brain Sci. 22. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, April 2004, S. 203–214, PMID 11301523.

- ↑ Baron, Robert A., Deborah R. Richardson, Human Aggression: Perspectives in Social Psychology, Springer, 2004, ISBN 030648434X, 9780306484346

- ↑ Albert, D.J., M L. Walsh, and R H. Jonik. "Aggression in Humans: What is Its Biological Foundation?" Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 4 (1993): 405-425.<http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=8309650&dopt=Abstract>.

- ↑ Beresford, B., E F. Coccaro, T. Geracioti, J. Kaskow, and P. Minar. "CSF Testosterone: Relationship to Aggression, Impulsivity, and Venturesomeness in Adult Males with Personality Disorder." Journal of Psychiatric Research (2006).<http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=pubmed&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=AbstractPlus&list_uids=16765987&itool=iconabstr&query_hl=4&itool=pubmed_docsum>.

- ↑ Chandler, D W., J N. Constantino, F J. Earls, D Grosz, R Nandi, and P Saenger. "Testosterone and Aggression in Children." Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology 32 (1993): 1217-1222.<http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=8282667&dopt=Abstract>.

- ↑ Hillbrand, Marc, Nathaniel J. Pallone, The psychobiology of aggression: engines, measurement, control: Volume 21, Issues 3-4 of Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, Psychology Press, 1994, ISBN 1560247150, 9781560247159

- ↑ a b c d e f Niedenthal, P.M., Kruth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2006). Psychology and emotion. (Principles of Social Psychology series). ISBN 1-84169-402-9. New York: Psychology Press

- ↑ Wilson, Tracy V. "How Women Work" How Stuff Works. Accessed April 2, 2008.

- ↑ Reeves, Jamie Lawson "Women more likely than men to but emotion into motion". Vanderbilt News. Accessed April 3, 2008.

- ↑ Stephanie Rosenbloom "Big Girls don't cry". New York Times. Accessed Feb 15, 2012

- ↑ a b Murray, Bridgett "Boys to Men: Emotional Miseducation". APA.

- ↑ Nolen-Hoeksema S: Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory. In: Psychological Bulletin. 101. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, 1987, S. 259–282, doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.259, PMID 3562707.

- ↑ Hall Judith A: Gender effects in decoding nonverbal cues. In: Psychological bulletin. 85. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, 1978, S. 845–857, doi:10.1037/0033-2909.85.4.845.

- ↑ Judith A. Hall (1984): Nonverbal sex differences. Communication accuracy and expressive style. 207 pp. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ Judith A. Hall, Jason D. Carter & Terrence G. Horgan (2000): Gender differences in nonverbal communication of emotion. Pp. 97 - 117 i A. H. Fischer (ed.): Gender and emotion: social psychological perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Agneta H. Fischer & Anthony S. R. Manstead (2000): The relation between gender and emotions in different cultures. Pp. 71 - 94 i A. H. Fischer (ed.): Gender and emotion: social psychological perspectives. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Ickes, W. (1997). Empathic accuracy. New York: The Guilford Press.

- ↑ Klein K. Hodges S.: Gender Differences, Motivation, and Empathic Accuracy: When it Pays to Understand. In: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 27. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, 2001, S. 720–730, doi:10.1177/0146167201276007.

- ↑ Schaffer, Amanda, The Sex Difference Evangelists, Slate, July 2, 2008 http://www.slate.com/id/2194486/entry/2194489

- ↑ a b Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite document

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite doi

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite pmid

- ↑ Leonard C. M., Towler S., Welcome S., Halderman L. L., Otto R. Eckert, Chiarello C.: Size matters: Cerebral volume influences sex differences in neuroanatomy. In: Cerebral Cortex. 18. Jahrgang, Nr. 12, 2008, S. 2920–2931, doi:10.1093/cercor/bhn052, PMID 18440950, PMC 2583156 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Luders E., Steinmetz H., Jancke L.: Brain size and grey matter volume in the healthy human brain. In: NeuroReport. 13. Jahrgang, Nr. 17, 2002, S. 2371–2374, doi:10.1097/00001756-200212030-00040, PMID 12488829.

- ↑ RJ Haier, RE Jung, RA Yeo, K Head, MT Alkire: The neuroanatomy of general intelligence: sex matters. In: NeuroImage. 25. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 2005, S. 320–7, doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.11.019, PMID 15734366 (themindinstitute.org [PDF]).

- ↑ Kimura, Doreen (1999). Sex and Cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-11236-9

- ↑ Ho, K.C.; Roessmann, U.; Straumfjord, J.V.; Monroe, G.: Analysis of brain weight. I. Adult brain weight in relation to sex, race, and age. In: Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 104. Jahrgang, Nr. 12, Dezember 1980, S. 635–9, PMID 6893659.

- ↑ Ankney, C.D.: Sex Differences in Relative Brain Size: The Mismeasure of Woman, Too? In: Intelligence. 16. Jahrgang, Nr. 3–4, 1992, S. 329–36, doi:10.1016/0160-2896(92)90013-H.

- ↑ Faverjon, S.; Silveira, D.C.' Fu, D.D.; et al.: Beneficial effects of enriched environment following status epilepticus in immature rats. In: Neurology. 59. Jahrgang, Nr. 9, November 2002, S. 1356–64, PMID 12427884 (neurology.org).

- ↑ Lloyd, Robin. "Emotional Wiring Different in Men and Women", LiveScience, April 19, 2006. Accessed April 2, 2008.

- ↑ Cahill, L. et al. "Sex-Related Hemispheric Lateralization of Amygdala Function in Emotionally Influenced Memory: An fMRI Investigation." Learning & Memory. 11 (3): 261 (2004).

- ↑ Cahill, Larry. "His Brain, Her Brain". Scientific American. May, 2005. Accessed April 2, 2008.

- ↑ a b Motluk, Alison. "Women's better emotional recall explained". NewScientist. July 22, 2002. Accessed April 2, 2008.

- ↑ Canli, T. et al. "Sex differences in the neural basis of emotional memories". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (16): 10789. (2002).

- ↑ "Sexes handle emotions differently", BBC News - Health, July 23, 2002. Accessed April 2, 2008.

- ↑ Douglas, Kate. "Cherchez la différence". NewScientist. April 27, 1996. Accessed April 2, 2008.

- ↑ "Gender Differences In Brain Response To Pain". Science Daily. November 5, 2003. Accessed April 2, 2008.

- ↑ Resnick, S.M.; Berenbaum, S.A.; Gottesman, I.I.' Bouchard, T.J.: Early hormonal influences on cognitive functioning in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. In: Developmental Psychology. 22. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, März 1986, S. 191–8, doi:10.1037/0012-1649.22.2.191.

- ↑ Berenbaum, S.A.; Hines, M.: Early androgens are related to childhood sex-typed toy preferences. In: Psychological Science. 3. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, 1992, S. 203–6, doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00028.x.

- ↑ Janowsky, J.S.; Oviatt, S.K.; Orwoll, E.S.: Testosterone influences spatial cognition in older men. In: Behav. Neurosci. 108. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, April 1994, S. 325–32, doi:10.1037/0735-7044.108.2.325, PMID 8037876 (apa.org).

- ↑ Gouchie, C.; Kimura, D.: The relationship between testosterone levels and cognitive ability patterns. In: Psychoneuroendocrinology. 16. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, 1991, S. 323–4, doi:10.1016/0306-4530(91)90018-O, PMID 1745699.

- ↑ Nyborg, H.: Performance and intelligence in hormonally different groups. In: Prog. Brain Res. 61. Jahrgang, 1984, S. 491–508, doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(08)64456-8, PMID 6396713.

- ↑ Eals, Marion, and Irwin Silverman. 1992. Sex differences in spatial abilities: evolutionary theory and data. In The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture, edited by J. H. Barkow. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Jones, Catherine, and Susan D. Healy. 2006. Differences in cue use and spatial memory in men and women. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B 273:2241-2247.

- ↑ a b David C. Geary: Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences. American Psychological Association, 1998, ISBN 1-55798-527-8.

- ↑ New, Joshua, Max M Krasnow, Danielle Truxaw, and Steven Gaulin. 2007. Spatial adaptions for plant foraging: women excel and calories count. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B 274 (1626):2679-2684.

- ↑ Stefan Lovgren: Sex-Based Roles Gave Modern Humans an Edge, Study Says. In: National Geographic News. Abgerufen am 3. Februar 2008.

- ↑ Cordelia Fine: Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference. W. W. Norton, 2010, ISBN 0-393-06838-2, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001005.g001.

- ↑ a b Bombardieri, Marcella (January 17, 2005). "Summers' remarks on women draw fire", The Boston Globe, reporting the remarks of Larry Summers at a January 2005 conference.

- ↑ Transcript of Summers' remarks at NBER Conference on Diversifying the Science & Engineering Workforce.

- ↑ Summers' initial response to controversy.

- ↑ Hernandez, Javier C. (Feb 22, 2006). "Summers resigns: Shortest term since civil war; Bok will be interim chief", Harvard Crimson.

- ↑ Seward, Zarachy M. (May 16, 2005). "University Will Commit $50M to Women in Science", Harvard Crimson.

- ↑ "The Science Of Gender And Science", Edge.

- ↑ Letter from Prof. J. Philippe Rushton to the Dean of Aarhus University in defence of Prof. Nyborg, August 9, 2006.